Interviews To 1985

...From his first theatrical involvement in a boy scout group in the mid 60's to his uniquely styled, self-publicised plays at school, Clive began to display talent as well as ungoverned enthusiasm for all things Thespian. The establishment of a circle of like-minded friends led to the staging of all manner of plays, increasingly self-penned, and the creation of the Dog Company. From the burlesque to the histrionic, with no fear of complex mime or frankly bizarre pieces, Clive began to gain an admittedly small reputation. In the manner of the larger-than-life Grand Guignol pieces he so favoured, the tales written for pleasure and for his friends were soon to develop into the world-wide-selling Books of Blood. And so it began...

Macca, The Saint And The Screen Goddess, 2008

Clive Barker - Making His Actions Speak Louder Than Words...

By Joe Riley, (i) Liverpool Echo, 8 April 1976 (ii) in Joe Riley's book of interviews, Macca, The Saint And The Screen Goddess, 2008

"I'd always been interested in acting, right from my schooldays when I scripted farces with a friend. Gradually, my ideas changed and became more orientated towards mime. I helped form a group called Theatre of the Imagination. We played at the Everyman when the professional company was in rehearsal or on leave. I suppose you could have called our format multi-media, in that we used spoken word, mime and dance."

Linda Talbot At The York And Albany

By Linda Talbot, The Hampstead and Highgate Express, 10 July 1981

"We want to combine well-told and often outrageous

stories that involve not only the actors but the

audience's imagination, as well as visual effects

and wit - theatre that entertains and asks questions...

"We're completely independent and receive no funding

except what we earn through fees and the box office -

a situation we're eager to change. But in spite of

economic problems, we're growing fast."

Liverpool Echo, 23 March 1984

Clive : A Happy Horror Writer

By Joe Riley and Peter Trollope, Liverpool Echo, 23 March 1984

"I suppose it's because I love anything that's taboo. I dare to talk about things which others push to the back of their minds."

Clive's Chilly Work

By Peter Rhodes, Birmingham Evening Mail, 16 April 1984

"If people buy my books and don't get scared then what right have I to be called a horror writer..?

"Things still growl in the dark but they have to be put in a new context, in the environment that

people know. This is where the monsters are, not in some dusty old vault.

"People in 1984 are aware of so much more than 100 years ago - and the more you know, the

more there is to be scared of."

Blood Lines

By Giovanni Dadomo, Time Out, No 723, 28 June to 4 July 1984

"I never actually stopped reading horror stories or seeing the movies, I just became less public

Time Out, No 723, 28 June to 4 July 1984

about it. There's a terrible attitude of condescension - even now, people who find out what I

do tend to ask what else I do, what I do when I'm being 'serious'...!

"There's nothing in any of the books [of Blood] that I'd consider gratuitous. To me a book

or a film - something like Driller Killer or I Spit On Your Grave, say - it's only gratuitous if

the violence is all there is. There's got to be something else.

"But on the other hand, you have to remember that if you pick up a horror book in the first place

you're asking to be horrified, to be frightened. And I've got to deliver; I set out to

scare people. And one of the tools I deal with is sinews and blood."

Phenix, No. 34, March 1993

Fear, No 15, March 1990

Interview

By Gilles Bergal, (i) Mater Tenebrarum, 1985 (Note: interview

took place at Fantasycon IX, 16 September 1984) (ii) Excerpted in Fear, No 15, March 1990 and

translated from the French by Jean-Daniel Breque (iii) Phenix, No 34, March 1993

"After I finish the stories for Books of Blood Volumes Four, Five and Six, I would like to write a big thriller and also some fantasy novels. I don't want to be labelled as a horror writer, not because I don't like horror, but because I want to do a lot of other things. I want to do whatever it's possible to do in the field of imaginative writing. It excites me. I want to write science fiction. I want to write fantasy, and so on. I would love to do illustrated books. I don't think it's very wise to be put in a certain slot. People say, 'Oh, he's a horror writer,' and that's it. It's much better to do a lot of things. The trouble is, you have to go slowly, and I'm very impatient; I want it to happen fast, and it takes some time to get these things done, but next year I hope to do several of them, including the first part of a big fantasy novel, and I would like to write an erotic novel, a big, erotic novel."

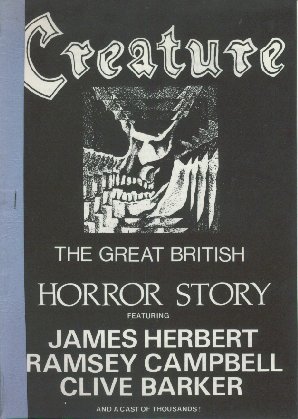

Clive Barker

By Nick Hasted, Creature, No 4, 1985

"The kind of horror which is all suggestion, and undertow, and 'it's what you don't see

that horrifies you' kind of stuff - that doesn't do a thing for me. I like things to

come out and grab me, I like my horror in 3-D - Ramsey [Campbell] says I write in

technicolor - it's the same thing. I like imagining horrors in detail. I like to be

able to give the reader everything I can imagine on a subject. I dislike intensely - there

are a few exceptions to this, like M.R. James - but I dislike intensely the kind of

horror that doesn't give you at least a glimpse of what you're supposed to be scared of.

Of course, you can go too far on that, you can give people so much that there's nothing

left to their imaginations... I think the idea is to give them just sufficient to get

their imaginations going - Bradbury's a wonderful, wonderful example...

Creature, No 4, 1985

"Horror fiction is about confrontation. And the thing is, I don't think it should be

about confrontation and then rejection. I think it should be about confrontation and then

acceptance... In the bulk of Steve King's work, for example, there is confrontation with

the forces of evil, moral disintegration, social corruption - and for the most part those

forces are overcome. It may very well be that there are losses, there will be sacrifices

along the way, but there is a final rejection - the house is clean, the beasts are thrown

back into the dark again. In my kind of horror fiction, and my vision of what's

interesting about horror fiction, you say, 'Let's see what the Beast looks like - does

it in any way resemble us? Is it interesting? Should we be scared of it at all? And

let's see what happens if we're nice to it, if we make love to it, if we take it into the

family', and so on. At the end of practically all my horror fiction, the beast remains

intact in some way or other. It may remain as a memory, it may remain as a physical

entity, it may have been sent to ground, to appear again. Ramsey said once,

I think in the introduction, that the stories were 'weirdly optimistic' and I think that's

sort of true, I hope it's true. I look upon them as being optimistic tales, because

they're about a widening, a broadening of what is possible, whereas I think the classic

horror fiction, in recent years at least, has been about the narrowing of what is

possible. You know, it's saying, 'Oh, this is not me, this does not belong to me, I

throw this away, I discharge this'. Whereas I say, 'Let's look at the Beast closely.

Let's see if it isn't rather interesting, rather worth our affection."

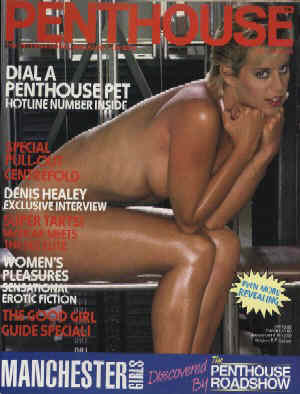

Penthouse, Vol 20, No 5, May 1985

View From The Top: Words

By Neil Gaiman, Penthouse, Vol 20, No 5, May 1985

"Once in a while it can be nice to kill someone who absolutely doesn't deserve it. Horror fiction should be about arbitrariness. If you have a moral viewpoint then arbitrariness is something you'd reject. If, however, you think as I do that everything is up for grabs - philosophically, theologically, sociologically - this may indeed be the first century in the history of the world in which everything is up for grabs. We speak of a godless society, denuded of political beliefs, punchdrunk and reeling from future-shock: this either makes us incredibly weak or it makes us incredibly strong. And it's up to us. Personally I feel strong."

Enfant Terrible

By Christopher Tookey, Books and Bookmen, July 1985

"I can't take the argument terribly seriously that going to view 'Macbeth' will make you go and behead your best friend in bed. There may be some useful sociological purpose served by horror fiction, but I wouldn't argue that either. People have an appetite for this kind of thing, and most appetites, if they are healthy people, are healthy things. The repression of the desire to see blood, the desire to see death, seems to be fundamentally unhealthy."

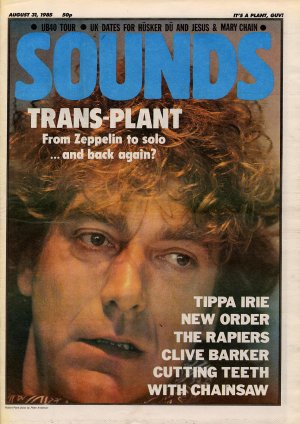

Bookworms - Dark Star Of Horror

By Edwin Pouncey, Sounds, 31 August 1985

"I had a couple of notions about the Faust story. I mean, there's no

argument that Faust must be one of the oldest horror stories extant as

a basic formula: man makes pact; pact-keeper comes seeking retribution,

now read on, is a basic structure and, I think, a very potent one. I

Sounds, 31 August 1985

wanted to see what sense I could make of these notions in the late part

of the 20th century. What does damnation and all that stuff actually

mean now? What would a man sell his soul for? What is it that we could

call a soul which we could sell in the first place? And under those

circumstances, assuming that such a sale was made, what would Hell be?

What would the Devil have in his arsenal to claim a new Faust?

"I looked at all these things and The Damnation Game is the result. The

book has done a lot of things I wanted it to do, it's a horror book in

one obvious sense and a thriller in another sense. I've attempted to

write a horror novel that is also a mainstream novel."

Scream/Press/Release, Vol 1 No 4, September 1985

Bloody Books Coming Soon

By [Jeff Conner], Scream/Press/Release, Vol 1 No 4, September 1985

"Right now all I'm doing is working on the screenplay to Rawhead Rex, re-writes

basically. It's going very well and the production company has been very agreeable

about all the violence. I think they're getting used to me. Shooting could start very shortly.

"We've got an 8 ft. actor to play Rawhead and a top-notch special make-up person

is doing the mask and such. It should be great fun, but I guess everyone says that

at the start of any picture, especially of a 'monster' movie."

Book News

By [ ], The Bookseller, 7 September 1985

"I want to disturb people but I would hate to think that I was considered only to be capable of finding different ways of representing agony."

Master Of The Macabre

By Joe Riley, Liverpool Echo, 1 October 1985

"Yes, the long days of the dole queue. Nine years of them. In the end, they even called me in for one of those heavy interviews where they

locked the door.

"I told them I wrote plays and produced a whole file of them out of a bag. I might not have been paid for them in those days, but I

believed in what I was doing.

"I got so used to working like that, that I have no real intention of giving up now. The only difference is that people are suddenly

prepared to pay me fabulous sums for it."

Programme - 29th London Film Festival, 1985

Underworld

By [ ], Underworld production notes reprinted in the 1985 London Film Festival Official Programme, November 1985

"There are some wonderful monsters lurking in the pages of my short stories - Rawhead Rex, for instance, nine feet of lumbering death."

Horrorshow Hotel

By Henry Jackson, Jamming!, No 34, November 1985

Jamming!, No 34, November 1985

"The most fascinating thing for me is the process of the imagination.

I'm not by nature a realist. I don't care for the realistic in theatre,

movies or books. What interests me much more is the imaginative work

in which one feels that the dream life, the life of the subconscious

imagery shares the page or the stage with the kind of life we

superficially live. The marriage of the two kinds of reality is

fascinating. I hate the tyranny of the real. We live inside our minds

and our minds are a mixture of things experienced through our senses;

things dreamt and things hoped for and things that operate through

memory. All of this is in some kind of constantly simmering state. It

has always drawn me, that one should be representing the complexity of

experience, a great deal of which is imagined or dreamed.

"It's okay to suffer the accusations of triteness [of the horror genre]

if I go into a railway station and find that my books are being bought

by sober suited businessmen on the 9.15 from Cheltenham, and are

faintly subverted. I will happily risk the dangers of trivialisation

in order to get through to people on that level."

Kaleidoscope

By David Roper, BBC Radio 4, 11 November 1985

"I have no taste for the real. I mean, one has to live that: let's not embark upon a pursuit of the real in art as well. I'm much happier going to the limits of my imagination whenever I can. How far can imagine this? How intricately can I imagine this? How outrageously can I imagine this? And the imagination is the pump, if you like. Now, the precise direction of each piece that I do is dependent upon what I want to get from an audience; whether I want to get a belly-laugh or writhing nausea...

"I think one should be aware that the small nick on the finger of somebody you care about means a good deal more than slitting the throat of somebody you couldn't give a damn for. There are writers who write, I think, much more outrageously gory stuff, consistently gory stuff, than I do. Stuff in which every three pages you're going to find decapitations and disembowellings and so on. It seems to me the degree of gut-wrenching effect is dependent - as dependent, maybe more dependent - upon how much you care, and that's to do with characterisation, to do with plotting."

Clive Barker

By Kim Newman, (i) Interzone, No 14, Winter 1985/86 (ii) translated into German in Science Fiction Media, No 34, March 1987

"[I have been] a pretty eclectic reader. I was never

obsessed by any particular genre. As far as the

Interzone, No 14, Winter 1985

Science Fiction Media, No 34, March 1987

fantastique is concerned, I read Poe and Bradbury and

fairly standard people. The only people who I sort of

discovered for myself were Arthur Machen and David

Lindsay. I suppose Eddison and Dunsany also. There were

negative influences too, trudging through 'The Well At

The World's End'. Fritz Lieber I like a lot. He's

approachable and witty. His Fafhrd and Grey Mouser

stories please me in a way that the Conan stuff never

did. It always seemed witless to me. I like to hear

the author. You can hear Lieber's voice very strongly.

There were other influences which were every bit as

strong as the fantasy influences. Stevenson for instance

. I go back and back to Stevenson... I adore Biblical

epics. Horror movies. Later on, 'Fantasia'. If I had to

choose one movie it would be that just as a pure

sensation. Cartoons are a huge influence. It's pure

cinema. You get a kind of visual control which can make

for stunning stuff. And film noir for the humanity, for

the story. I love notions of discovery, the

psychoanalytic subtext of noir. And Donne, Webster,

Shakespeare, Marlowe, those guys. They were populists

who were shamelessly interested in weighty material.

Now that's what I'm up to. I want to make popular

fiction which carries significance of some kind."

Dancing With The Dark - Vista paperback proof 1997

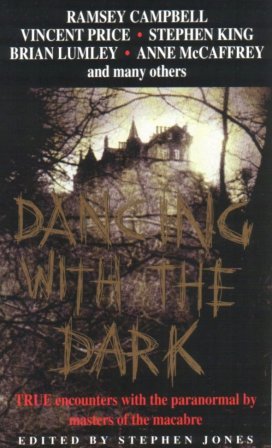

Dancing With The Dark

Dancing With The Dark - Vista, 1997

Faces of Fear - Pan, 1990

Faces of Fear - Berkley

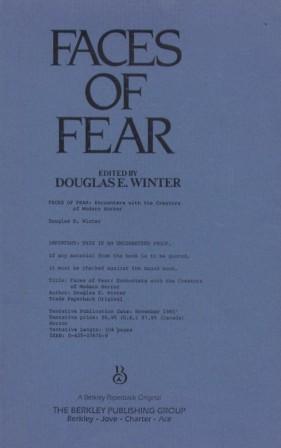

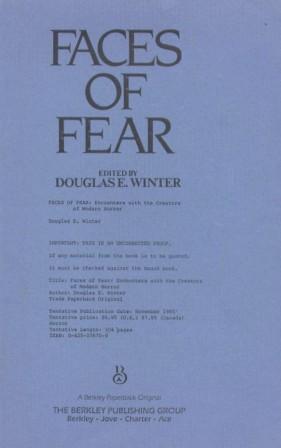

Faces of Fear - Berkley Proof

Give Me B-Movies Or Give Me Death !

By Douglas E. Winter, (i) Faces of Fear, 1985 (ii) Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden (iii) short extract presented as 'Life After Death' in Dancing With The Dark by Stephen Jones, 1997

"Hero and heroine should not walk hand-in-hand

into the sunset. There has to be a sacrifice, probably

has to be a lot of loss - love loss, limb loss. It's

not that nobody will survive, but those who do survive

aren't going to be in quite the same condition that they

were in when they started. It's important that people

be transformed in the action of the story. They may be

transformed in a very fundamental way: they may begin

alive and end up dead, they may lose limbs, they may

lose their sanity.

"Within the context of my fiction, I think such

changes are upbeat. People are given a moment of

revelation, which, I think, is just about the most

important thing in the world - moments where they see

themselves in relation to the imaginative elements

which have erupted into their lives. That happens again

and again in the stories, though not as a conscious

strategy. It's only as time has gone by that I've

realized that the stories are very much about people

accepting, embracing, celebrating the capacity for the

monstrous in the world. I think it's very important to

relate intimately to the dark, to the most outlandish

parts of oneself, and of the world. That way, stories

about fear may even teach one not to live in fear."