Interviews 1991

...From the depths of his Nightbreed despair came the heights of Barker's greatest creative work - Imajica. As ever, his publishers allowed him the freedom of expression he would never find in Hollywood, and his readership were only too eager to wander with him about whichever Dominion he opened for them. If not intended as a reply to his critics, it must have at least served as salve to the wound, allowing him to bounce back with ever increasing plans for new work. After moving to L.A. in the spring, next up on the agenda was The Mummy (aka The Egyptian Project) - to be shot that summer. Planned as a movie of 'undiluted horror' it was never to be and Barker's energies were directed towards Eden USA, updated drafts of Lord of Illusions and keeping a watchful eye on Bernard Rose's screenplay for Candyman. Meanwhile, that autumn Hellraiser III was being shot in N.Carolina and Salem ...

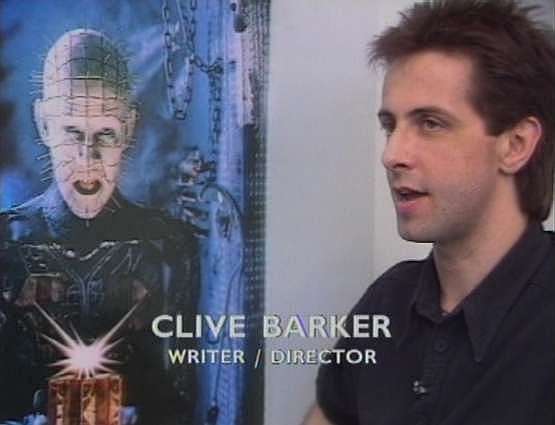

Fear In The Dark

Interview by [ ] for the UK Channel 4 documentary Fear In The Dark, 1991

"Wouldn't we like to believe that some of the things that happen in horror fiction were plausible, even though the consequences of them may be terrible within a particular drama? It might nevertheless be rather reassuring to know that the Devil existed because then, by extension, do did God. It might be rather reassuring that zombies can inded break in through the french windows because, well at least there's life after death."

The Edge Interview

By David Alexander, The Edge, 1991

"I turn on MTV and have a good time with it, but we have our three-score years and ten, and as practitioners in a particular area of art the idea of making something disposable turns my guts to ash. To spend the amount of time and anger and all that stuff making something which is really tomorrow's chip-paper is to reduce oneself to the status of Alexander Walker! And that's a long way down!"

What's Up Joe Dante?

By Grant Littlechild for the documentary What's Up Joe Dante?, 1991

"Joe brings - even to relatively benign projects - a sinister edge, a darker tone which is, I think, regrettably missing in the work of a lot of other American fantasy filmmakers who move towards the sickly sweet, towards the saccharine. I think that one of the things which distinguishes Joe's work and makes his work, for me, more interesting than many of his contemporaries is this desire to mingle the grim and the ghoulishly funny."

Hell Is Where The Heart Is

By Dan Sicko, Anti-Matter Magazine, Issue 2-4, 1991

"The whole Christian structure has been taking a larger and larger place in my material, not least because it's so much a part of our culture, even though very few of us now go to church. Fantastic fiction has, by and large, passed by the Christian mythologies, and gone to Norse or Greek mythology for its inspiration. Think of Tolkien, who has probably written the definitive work of fantasy in the 20th Century in 'The Lord of the Rings'. Even though there are Christian values buried very, very deep in that book, the prime structure is very non-Christian, it's Norse or Celtic. And I'm not very interested in what the Norse believed, I'm interested in what our culture has buried inside it.... I've always claimed that fiction has the ability to address realities of the world, rather than just be an escape valve... Many of the things which Christianity holds dear I find deeply offensive."

Imajiman

By Jon Gregory, Hellraiser, No 2, 1991

"I believe in what I write - not literally in that I believe with the right incantations I could step through into the Imajica, but I believe in the philosophies that underpin my work. Obviously in the case of Weaveworld, because it was set in Liverpool, it had large autobiographical slices in it. I mean, I know all those places very well. I stayed in the hotels that are mentioned in Imajica... I've kept company with the same kinds of people as Gentle and Judith. Obviously, when you step into the worlds of the imagination - the Imajica and the Fugue - you become even more autobiographical, curiously, because when it is all invention, it really is yourself that you are putting down in writing. All this material is pouring out of your subconscious and onto the page."

Cabal

By Luis Alcaide, Philippe Guézennec and Patrick Nadjar, L'Ecran Fantastique, No 118, January 1991 (note - translated from French)

"I like these [surrealist] images; they sometimes have a strange beauty. I think that Pinhead in Hellraiser has this odd aestheticism. Several of the Nightbreed also enjoy it. Shuna Sassi is splendid, sexy and attractive. The creatures of Nightbreed form part of the European vision of what a monster can be. When Pavlou adapted Rawhead Rex and Underworld, it was American films that he wanted to make. It is not my cup of cup of tea. And if Americans do not like my style, what can I do about it?"

Gangsters Vs. Mutants

By Philip Nutman, Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden, 1991 (Note: this is a completely updated and re-written version of the 'Meet Clive Barker' interview in Fangoria, No 51, January 1986)

"The thing about fantastic fiction is that it makes flesh of metaphor. I hope with 'Underworld' to embody that; here are people whose dreams are made flesh and are suffering for it. But we, the audience, desperately want them to survive because they teach us about ourselves - our dreams and hopes."

A Dog's Tale

By Peter Atkins, Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden, 1991 (Note: interview took place in 1988)

"It's like what we were doing was chucking as

many balls in the air as we possibly could and then,

when they fell, trying to catch as many as possible. And,

of course, we couldn't catch them all. And I'm in love

with Art that can't catch all the balls... And I know this

means that the work is in a way flawed. I know 'Hellraiser'

is flawed. I know 'Weaveworld' is flawed. But they are

flawed because they over-reach. And I celebrate over-reaching.

I measure the excellence of a work of Art by how much it

over-reaches."

Blood And Cheap Thrills

By Alan Jones, Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden, 1991 (Note: this is a complete 1991 rewrite/update of the Rawhead Rex article from Cinefantastique, Vol 17, No 2, March 1987)

"At least on 'Underworld' I used to come off the phone shaking with rage because I knew they were heading in the wrong direction. On 'Rawhead' the phone never rang once - I was in the dark and still being fucked over and there was nothing I could do about it even though I knew everything I wrote in the script was right. I'd be on the 'Underworld' set and I'd hear an actor ask George, 'Hey, is this dialogue up for grabs?', and he'd say, 'Sure.' The consequence was nothing I wrote was left in the script because all the actors rolled with it."

Clive Barker

By Marc Toullec,

(i) Mad Movies, No 69, February 1991

(ii) Mad Movies 50 Ans, Hors-Serie No 69, November 2022 (note: translated from French)

"I don't really like most horror films of the 1980s. The repetition bores me. I like the first Freddy, the first Halloween too, and even the first Friday the 13th. But Jason, with his hockey mask, has a limited register."

Fear Is The Key

By Sheila McNamara, [ ], January 1991

"Edgar Allan Poe was the greatest influence on me. He is the father of the mystery and arguably the originator of the science-fiction story, so the range of elements that comes into play in somebody who is unfortunately listed as a horror writer, like Poe, is large. Contemporarily, there's a lot of very diverse work being done. Ramsey Campbell is very different to Peter Straub, who in turn is doing something very different to the so-called splatter-punks. There are so many visions being explored that if I had to choose one book, it would be Peter Straub's Ghost Story.

"Stephen King's influence has made the genre socially acceptable. You no longer have to hide your copy behind the latest John Updike. He's written magnificent stuff. I greatly admire Thomas Harris, and Arthur Machen, an uncelebrated English writer, is worth a mention. My ultimate idol would have to be Poe, but for a living expert, I'm going to vote for Stephen King."

Luggage In The Crypt

By Nick Vince, Pandemonium, 1991

"Peter Pan has to be the book of my childhood. Come to think of

it, it's the book of my adulthood too. It's a book which, in

the reading of it, takes me back to editions that I've had and lost,

with various illustrators' work in them. It brings back moments

sitting reading it with my mother. It brings back my first contact

with the Disney cartoon. It brings back standing in the play-yard

when I was a kid, when the wind was really blowing, and closing my eyes,

spreading my arms and pretending I could fly. It brings back

childhood dreams of flying. It brings back the first encounter I ever

had with an invented world... Never Never Land was really the first

journey I took to an invented world

which I believed in wholly and

completely. I remember the immense solidarity that I felt with the

Lost Boys, with Peter,

with the Indians - how much I wanted to

be a Red Indian - how much the saving of Tiger Lily meant to me as a

kid, how much I wanted to one day wake up and save an Indian squaw

from drowning."

A Reader's Guide To History Of The Devil

By Peter Atkins, Pandemonium, 1991

"I don't like fourth-wall theatre. I don't like going to watch a bunch of people pretend I'm not there. The kind of theatre I like, and the kind of theatre I wrote, is all about acknowledging and confronting that artificial reality that a stage sets up. I like musicals, I like art theatre, I like mime. I like, as an audience member, to be involved, to be addressed, to be complicit."

So Many Monsters, So Little Time...

By Michael Brown, Pandemonium, 1991

"My father was in the Navy, my grandfather was a ship's cook and so he carried on the tradition. My godfather, who's now dead, unfortunately, was a sea captain. Many of my father's peers that I knew when I was a kid were related to the sea, to the river. All that stuff about the romance of the Mersey as detailed in Weaveworld I got from my father. Being taken down the Mersey and having the origins and the destinations of the ships being pointed out to me - this ship was going to Rio de Janeiro and this ship to Jamaica - made a very strong impression on me... It was far away places with strange sounding names. Now, of course, all that's gone from Liverpool because the docks have closed down and the river is basically empty. I think ships carry with them immense romance. I certainly think, if you look out on any sea, if you... there was one day when we were having a hell of a day in Los Angeles and I went down to the coast and just sat and watched the sea. It's extremely soothing and all your problems seem very miniscule. You go back with a little ocean in your ears, which doesn't hurt."

Fangoria Weekend Of Horrors

Transcript of a talk by Clive Barker, Weekend of Horrors, New York, 5 January 1991

"[Imajica contains] sex acts unattainable by mortal man - I know, because I tried!"

Fangoria Weekend of Horrors

Transcript of a talk by Clive Barker and Doug Bradley, Weekend of Horrors, New York, 6th January 1991

"[]"

Hellbound And Ungagged

By Dave Hughes, Speakeasy, No 117, February 1991

"I don't believe [ordinary people] really exist. They exist in Norman Rockwell's vision of the world, but not in mine. The closer you get to people, the more you realise (and, hopefully, celebrate) their peculiarities. People are peculiar. There isn't this sort of homogenised, rather bland creature that is The Good Guy. People have quirks and twists and perversions and paradoxes. Their strengths often come from very morally dubious sources; their weaknesses often come from morally superior sources. Basically, I think people are... weird."

Hall Of Fame

By Philip Nutman, Fangoria, No 100, March 1991

"There are a number of magazines that deal with the

genre in different ways and I find it divisive and

foolish that people have this constant demand on one side

or the other, that their way is the only way. It's a

single-mindedness which is wholly against the spirit of

the field in which we're working. The genre celebrates

variation, the imaginative, and allows people great

freedom. What distresses me is other people in the

genre, other magazines, holding up Fangoria as

somehow being syptomatic of some kind of sickness in how

the fans view the genre. It's an unacceptable position

to adopt. You go to the carnival and some people want

to ride the ghost train while others want the big dipper.

What's good is that both the ghost train and the big

dipper are there for us to ride on. There is a huge

readership for Fangoria. I've been to the

conventions, I've met these people. They are intelligent,

imaginative, they have an interest in a particular

aspect of the fantastique. They love the ghost train

ride. Great. So do I. There's room in the world for

every shade of enthusiasm. People shouldn't point the

finger just because you like a certain kind of picture

or enjoy splatter effects."

Clive Barker: Trust Your Vision

By WC Stroby, (i) Writer's Digest, March 1991 (ii) excerpted as 'On Writing Truthfully', The Basics of Writing And Selling Fiction, Writer's Digest Guide No 13, 1993 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"I feel as though I am writing a kind of fiction which relates to a whole texture of imagery which appears in painting and poetry and mythology and folklore. I wanted there to be in Weaveworld, for instance, echoes of Peter Pan, of the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, of the Book of Genesis, of William Blake. I don't want to be the literary equivalent of a movie brat quoting films. I'm not interested in pastiche. I'm trying to find my own route through to a kind of fiction which is at a crossroads of several other kinds of fiction - fantasy, horror, fairy tale fiction, visionary fiction, mystical fiction."

A Telephone Interview With Clive Barker

By Tyson Blue, Mystery Scene, No 29, April 1991 (Note: interview took place in February 1990)

"Hopefully I'm maturing as a writer and hopefully getting better at my craft. I'm becoming very, very interested in writing about certain kinds of individuals, and particularly in Great and Secret Show, finding myself responding to Tesla and Grillo and that whole texture of characters. I enjoyed writing, enjoyed the company of these people, and in Weaveworld, which was the other Big One, I enjoyed the company of the ideas, and characters were to some extent subservient to the scale of the ideas. Here the characters really rule the roost; the characters actually direct the course of the action in a significant way. Tesla, particularly, doesn't appear very much in the first fourth of the book. She seems to be a minor character, but becomes more and more important as the book goes on."

Fangoria Weekend Of Horrors

Transcript of a talk by Clive Barker, Weekend of Horrors, Los Angeles. May 1991

"We have a lot of problems making movies and one of them is 'testing.' You know about testing? It's where you get 500 people who

can't write in a room and show them the movie and then you ask them to set down their opinion on your picture - and it ends up

more violent, basically. Interestingly, I was speaking to Bob Shaye, who is obviously looking after Nightmare 6 at the moment, just

two weeks ago and he said, 'We've just been testing this movie and the audience says we don't want Freddy talking, we just want

him to kill more people' and there's something very boring about that. I mean, I love gross movies - you know I'm a Lucio Fulci fan,

OK I admit it, the moment with the splinter of the door and the eye in Zombie Flesh Eaters, or Zombie as it's known here, is as far

as I am concerned a masterpiece of extreme cinema - and so I have no problem with showing it when you need to show it, but I also

like horror movies for the moments of absolute surrealism, the moments of weird romance that horror movies can throw up (so to

speak!).

"It's one of the reasons why Bride of Frankenstein is my favourite horror movie, because Bride of Frankenstein contains, if you think

about it, extremely weird stuff, I mean really weird stuff. Here is this guy who's dead, he's been resurrected from a burning mill, and

they're going to make him a girlfriend - that's the basics and for 1931 / 1932 that's a pretty wild idea right there - I mean what are the

babies going to be like? So it's a slightly strange idea right off. Then you get Ernest Thesiger as Doctor Pretorius who is absolutely

amazing with his little penchant for gin and all that kind of stuff - 'it's my only vice,' he says, it's just great stuff. And the little

homunculi inside, it's just wonderful. It's full of surreal moments. I have a horrible feeling that if we were to show Bride of

Frankenstein to 500 people who can't write, from the Valley, and say what do you think of this movie, they would say, 'Duh...?

What does bride mean...?' You're dealing with that level of comprehension all the time, so that's a problem.

"We tested this movie [Nightbreed], we tested it twice with that ending and the audience said, sorry, don't like that ending and

Twentieth Century Fox said, OK, get rid of it. That's the way you go... Originally Decker died... and all that material is in the

vaults somewhere, so maybe we'll get it in the uncut version one of these days."

Clive Barker: On Nightbreed And More, Part Two

By [ ], Nightbreed, Vol 1 No 3, July 1991

"I would like to feel that I'm not just celebrating my own imagination, but celebrating what I do, a tradition of

Nightbreed, Vol 1 No 3, July 1991

imagining. That's why I'm so hot on literary tradition and all of that. I think that the tradition of the fantastic is horribly misrepresented, simply because the mainstream has repeatedly snatched great chunks of the fantastical tradition for itself. What it leaves is often the genre's weakest brethren. I want to be able to reinstate the fantastic.

I think that the only way I can validate myself is to see myself belonging to a very straightforward and simple tradition of the story teller, who is plugged into Jungian stuff. It's not really a question of echoing, but really advancing the stories. There is a revisionist folklore. That is plausible. It's not a contradiction. You can come at those forms and flip them around.

"It's important to be modern. I don't think that just echoing the old forms is good enough. It may be entertainment, but it may end up being nothing more than that. Willow, to take a case in point, echoes the old forms. You can check them off down the line. We owe the tradition more than that. We owe the tradition constant injections of originality. Trying to find new ways to tell the old stories, or ways in which the old stories can be made fresh by actually changing something about their subtext. I can validate myself within that system.

"That becomes a very simple mental process for me. So, if at the end of my life they say, 'He added a few more of those story forms, or twists on those story forms to the canon,' then that will be just fine. I love that idea."

New Releases

News by Michael Brown (?), Dread, No 1, July 1991

"[Imajica] is a big book. The working title for it was Tales of a Wanderer in the Five Dominions. Of the five dominions, one is Earth, the other four aren't. It's about the history of magic going back to 18th century England, and the claims that the mythical have on the mundane. It's set in New York, London, in the past, in the present and in four worlds of very different kinds. There's a large romantic element in it and a large sexual element - or should I say erotic rather than sexual? I think the people who enjoyed Weaveworld are going to find many of the same themes taken up afresh. The element of horror which has been diminishing in my work is still there, but it's not as important as the element of the fantastique."

Clive Barker's Letter From America

By Allan Bryce, The Dark Side, No 10, July 1991

"The problem with mainstream cinema is the desire that the producers have to iron out the quirks in performances and direction that make movies personal. Why do we go to art? Why do we go to a book, a painting, or a movie? I think we go to share somebody else's imagination. We don't go to share the imagination of a committee. So many movies are made by committees, particularly the large scale ones... that kind of movie leaves me completely cold, because there's no personality in it."

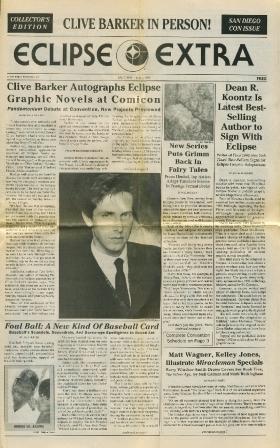

Eclipse Extra, 2 - 7 July 1991

Clive Barker Autographs Eclipse Graphic Novels At Comicon

By Michael Millett, Eclipse Extra, 2 - 7 July 1991

"I take comics very seriously, and I want [comics fans and retailers] to know my commitment is long-lasting... It's been the case that at signings I've met the fans of the written material and the movies, but I have yet to connect with the people who buy the comics, to dialogue with them. This is a great chance to get a sense of what the audience is and what they want, so that we can serve them with the creations better in the future."

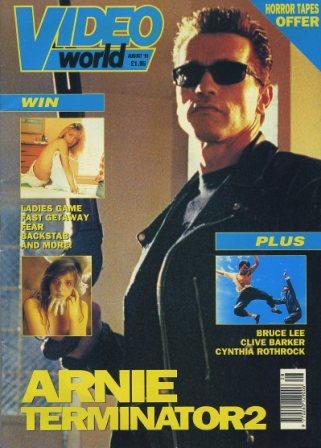

Breedin' Hell

By Allan Bryce, Video World, August 1991 (note: some sections identical to The Dark Side, July 1991)

"What happens to me is that I really don't know what I'm going to wind up with on celluloid when I start out. The movie  changes and changes, it's the same with a book, I have an idea when I start out and certainly the idea is there intact at the end. The idea I went into Nightbreed with was to make a movie which celebrated monsters, with strange creatures and dreams becoming real. I wanted to present the fantastical much more densely...

changes and changes, it's the same with a book, I have an idea when I start out and certainly the idea is there intact at the end. The idea I went into Nightbreed with was to make a movie which celebrated monsters, with strange creatures and dreams becoming real. I wanted to present the fantastical much more densely...

[On being approached to do a sequel] "The story of Nightbreed can run and run. There's no reason why those creatures couldn't return in one form or another. There are stories to be told, either on the printed page or in a movie. Whether I am the one who will be doing the telling is a matter for others to speculate on at the moment. One thing's for absolute certain and that is I'm more likely to do Nightbreed 2 than Home Alone 2."

Raising Hell In Hollywood

By Stephen Jones, Shock Xpress - The Essential Guide To Exploitation Cinema, August 1991

"If making movies was my prime objective in life, then I think I'd be

much more fretful than I am. I'm not going to Hollywood with the

blinkered intention of just making movies. Beverly Hills is somewhere

I will live and be involved in movie projects, but I also have a

four-book contract which obliges me to produce a book every eighteen

months or thereabouts.

"If you want to be a big success then it becomes a dick showing contest,

and that's not what it's about. It can't be about 'My book sold more

copies than your book.' It can't be about 'More people went to see my

movie than went to see your movie.' If it is about that, then Danielle

Steel must be an extraordinarily wonderful author because she sells so

many copies. You can't do calculations that way.

"What interests me is holding the vision: doing something that is yours

and making sure that it can't be like anyone else's."

Imajica - Press Release

By Craig Herman, HarperCollins Press Kit, August? 1991

"I like that term [fabulist]. For one thing it means liar, but also a maker of fables, a maker of things that are fabulous. That seems to me a good combination."

Horror Writer Makes Pact To Hold Back Nothing

By Valerie Takahama, The Orange County Register, 4 September 1991

The Orange County Register, 4 September 1991

"I have a kind of pact with my readers that I, Clive Barker,

will not flinch from describing everything I see in my mind's

eye - even the most violent, erotic, transcendental

elements...

"All of my favorite fictions celebrate the release of the imagination into the real

world. They're about the innocent and naive child - Dorothy, certainly, the

Darling family - who through some happenstance is whisked to a place where

the imagination is enthroned.

"As we grow old we're tempted away or shamed away by being told it's not part

of the real world. It's not going to help you put that second Porsche in the

garage. But we don't have to go to Bruno Bettelheim or Joseph Campbell to

intellectualize them for us. We know it in our hearts."

Clive Barker : A Pilgrim's Progress

By J.B.Macabre, Tekeli-li ! Journal of Terror, No 3, Fall 1991

"[Imajica] is not specifically concerned with millennilism, as are all

my other books. This sense of the apocalyptic has somewhat hung over

my books since The Damnation Game. In that sense, this has been an

ongoing theme in my work since 1986/87. It is present in Weaveworld,

with Uriel, the angel of the gates of Eden. Certainly it is present in

The Great and Secret Show, touching on the largest source of anxiety

of the 20th century : the atom bomb and our nuclear capability.

"Where Imajica differs, from all those books, is in its sense of the

material not being buried symbolically within the material text. Here

we're actually talking about divinity. We talk about the symbolic

becoming actual. That is a very different thing."

Fantasy's Future Probes The Mind

By Henry Mietkiewicz, The Toronto Star, 28 September 1991

"On a petty level, we fantasize what it would be like to make love to the guy or girl down the street. We fantasize about killing the boss with a hammer. We fantasize about winning an Oscar. On a deeper level, we fantasize what it would be like to have our dead relatives back, to have a final chance to make our peace with somebody we've lost, or to comprehend how and why we feel joy. Those extrapolations are a vital part of the texture of our experience on a day-to-day basis. They're not trivialities and they're not escapism. They are part of what makes us human. And in fabulist fiction, we have a form that says that the interior world, the exterior world, the world of dream and the world of living are all part of a continuum. What we writers try to do is dramatize that continuum and show how to get from realm to the other."

Out Of This World

By Wilder Penfield III, The Sunday Sun, Toronto, Showcase section, 29 September 1991

[Re Imajica] "I'd started this book about about a professional forger whose whole life was a lie, who fell in love with a creature - neither male nor female - that was literally the projection of sexual desire. That was the hook. I thought, 'That'll get me through 200 pages...' But I also wanted to write about magic...

"In crass versions of occultism, this means that you seek power over the oceans, like King Canute. In the poetic versions, the resonant versions, this means that you understand something about the rhythms of the oceans, as a dolphin does, which seems far more important...

"I completely believe that the Grand Scheme means us no harm whatsoever, and that whatever harm we do we visit upon ourselves... and that the road we are presently on in our three-score-years-and-ten is only part of a much longer journey..."

Fantastic Voyages: Exploring The Fantastique

Transcript of a panel discussion between Clive Barker, Richard Matheson, Charles Edward Pogue, D.C. Fontana, Haskell Barkin and Michael McDowell organised by Paul Chitlik, Matt Dorff and Patti Morrill for the Writers Guild of America, The Journal, Vol 4 No 10, October 1991

"I believe we are not aggressive enough in defence of our art. The fantastique delves into several things uniquely. However, we don't have a critical fraternity which addresses itself to the material we do, or even an academic fraternity which addresses the work in the kind of vocabulary that would elevate it to  what it should be. As a result, a number of assumptions follow about the triviality of the material - about how shallow we can be - which are utter nonsense. I argue that fantasy writing is not only 'as good,' it's actually better...

what it should be. As a result, a number of assumptions follow about the triviality of the material - about how shallow we can be - which are utter nonsense. I argue that fantasy writing is not only 'as good,' it's actually better...

"It's much safer and easier to make judgements about 'reality' because people think they live in it - mistakenly, but they think that.

Fantasy actually disturbs the critical fraternity. It throws them in a loop because they have to make a different kind of judgement. They certainly can't ask themselves, 'Is this real? Is Jeff Goldblum doing a very precise impersonation of a man who's turning into a fly?'

That's a very old, nineteenth century, problem about what art should do. It's a conceit that art should have some didactic purpose rooted in our everyday lives...

"We should stand up for certain narrative forms which are uniquely ours. The Fly is a unique way of talking about the human condition. There's no other way we can quite make that work except as a piece of fantastique."

Clive Barker

By Duane Swierczynski and Susie Calkins, Collegian, La Salle University, October 1991 (note: full text online at http://secretdead.blogspot.com)

"If you talk to 300 people, it really shouldn't be different from

talking to one or two. Basically, you're there to communicate your

ideas. There are things I want to say about the world, and about the

fiction I write, and about the relationship between the fiction I

write and the world. I'm always looking for a way to personalize

large ideas for audiences - each member of the audience should hear

my voice as an individual. You can be intimate with 300 people... You

don't think about it being 300 people. You think about it being

selective individuals with whom you are communicating your ideas. The

business that you're in, and the business that I'm in, is

communication. Later, you're going to be writing these words down,

trying to make a whole bunch of people who you don't know feel

something, something intimate to you. Your voice will be an intimate

voice, but you'll be whispering differently to each of those people.

I think that's what you hope to do. You want people to walk away

thinking, 'I know a little more about Clive Barker. And he wasn't a

high-falutin' son of a bitch...'

"Other people feel anxious about presenting themselves, for fear they

will be found lacking in some way. Maybe in my arrogance, I sort of

assume that what you see is what you get. I'm not everybody's cup of

tea, but that's cool. You can't be all things to all men."

Come On Down To Imajica

By Joe Schreiber, Michigan Daily, 1 October 1991 (note: full text online at http://www.scaryparent.blogspot.com)

"It's real difficult to make up your mind from moment to moment in the book [Imajica], and I love that ambiguity. I love that paradox. I love uncertainty,

because it's there anyway, and if you don't love it it'll just bite you in the ass. So, you may as well celebrate the fact that the world is in flux,

and your feelings are in flux, and you as an individual are constantly changing and transforming.

"I want to make books that allow the reader to celebrate that in themselves by showing the heroic and powerful and magical potential for those

qualities. So that the reader says, 'I see characters going through their lives and changing and confronting these ambiguities and actually being

stronger for it, rather than being stronger because they realize what evil was,' which doesn't pertain to the real world...

"I think the imagination is the only truth and every other experience, the pain one suffers, the people one loses, the people one gains, the loves one

has, are folded into the texture of your imagination, and reconfigured, and transfigured, and made over as metaphor, in order to achieve, hopefully,

some universality, so that it doesn't become some trite listing of events. When you write, you hope that fantasy will make the material sing, and

make people say, this is happening in my soul, too. This is happening in my spirit, too.

"And each book you fail, and you go on to the next one."

Looking For Wonderland With Clive Barker

By Robert W. Getz, (i) a Philadelphia arts newspaper, [Fall] 1991 (ii) From Hell And Beyond, January/February 1992

From Hell And Beyond, January/February 1992

"Women are these wonderful mysteries and they excite me on all kinds of levels. Their power over us is, I think, often a moral power as well as a sexual power. I think women, generally speaking, have a better sense of what is whole and good and sensible. The old feminist line, 'Take the toys from the boys' is an extremely sensible observation, you know?

"But there's something else, which is that in women's arrational, not irrational but arrational and apragmatic visions, is a sense that the world has to be embraced in all its mysteries and the moment you apply the rule of reason, you actually start to cut out a whole bunch of experiences. I am envious of that condition, imaginatively"

CSN Spotlight: Clive Barker

By Cliff Biggers, Comic Shop News, No 225, 9 October 1991

"I tend to make creative decisions by placing the strongest emphasis on grassroots work - that is, the material from which other media may spring. If I write a book, a comic book or a film or a television piece can come from that; but it's unlikely that if I spent a year making a television series, a book would spring from it. I believe the written word and illustrating lie at the very heart of my craft, my vision of the world. Everything else is a satellite to those twin suns."

Weird Clive Goes Erotic

By Ray Chatelin, The Province (Canada), 6 October 1991

"It's not the weird people you have to worry about. People who read my

books, I find, are in touch with their imaginations. It's people who

are tight-assed who worry me. People who have never allowed

themselves to experience the absurd can't possibly relate to the

ordinary day-to-day things - courage, love, all the solid things.

"That's what I really write about. It's just that you have to stretch

yourself finding them."

Clive Barker

By Suzi Feay, Time Out, 16 October 1991

"We are in a New Age, and there's much less embarrassment about that in California. Quite a big

thing there is the concept of the shaman; the person who goes on a spiritual journey and brings

back a record for the tribe. When Gentle sends his map of the Dominions back to Earth, it's also

my map, thr record of my 15 months on an imaginative journey. So I lay it before the tribe and say,

there it is, if it's worth anything to you...

"What's a British writer? I don't think I am one. I've always felt like an outsider. I think I'm

an Yzorderrexian writer! Clive Barker, born in 1952 in Smooke Street, Yzorderrex!"

Relaxing Gives Him The Creeps

By Serena Allott, The Telegraph, 19 October 1991

"I practice lucid dreaming: 'I am here dreaming and I am examining the dream as it's occurring.' It's not that difficult to get the knack of. All you have to do is carry into the dream state the attitude of participation. My conscious life involves putting dreams on a page...

"I don't like crowds of any kind. A dinner party of more than six people is not, for me, a pleasure. I get less social as I get older... I am very resistant to anything that keeps me away from the business of making these journeys into the fantastique. They are my reason for being on the planet, as far as I can comprehend, and I pursue them to the cost of almost anything."

Clive Barker

By Douglas Martin, Glasgow University Guardian, 30 October 1991

"By its nature, a popular novel is influential in theoretical, sociological and sexual ways. It is to be welcomed... I don't want to make 'art house' movies, I don't like them...

"[When writing], you've got sixteen months, your only motivation is yourself. There isn't a producer whipping you saying you have to get to work so you have to have pretty considerable reliance upon your own energies. In movies you have the problem of working with other people whose opinions you may disagree with, or who may want to do something completely different to your vision. It can be difficult."

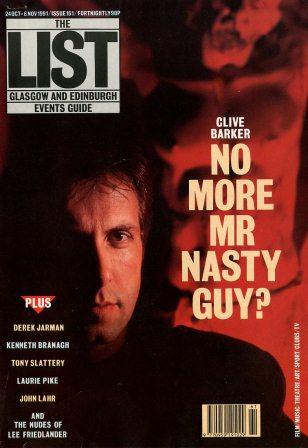

The List, 24 October - 6 November 1991

Magic Barker

By Alan Morrison, The List, 24 October - 6 November 1991

"Magic is, for me, the transformative capacity. In the Walt Disney version, this means that you point at a teapot and it becomes a carriage. I mean it in terms of transforming the psyche, in making our bland and mundane vision of the world into something wonderful and insightful. The magical process is, at least in part, a re-sensitising of the adult, returning the adult to the condition of wonder of the child, who sees things as fresh and clean and new."

Horror Novelist Digs Tales From The Dark Side

By Warren Epstein, Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, 31 October 1991

"This is the biggest story I know how to tell. It's a story of people who are transformed and who take on mythical dimensions. It's the

story of our lives, if we have healthy lives. People forget that before we were a taxpayer, we were spirits.

"I don't live next door to Mr. and Mrs. Middle America, I know the outsiders, the marginals, people who have deliberately exiled

themselves from the thrust of life. I'm not interested in the drama of the ordinary... I love watching anybody weird doing anything

weird to anybody else."

Raising Hell In Hollywood

By Janet Morris, Film Review, November 1991

"I feel that we have a culture that is sickened by strangeness, rather

than excited by it. We are all of us strange.

"Wouldn't it be wonderful to see yourself with the eyes of a stranger?

We're just so used to our own strangeness we find it easy to put down

other people's strangeness."

![Fantazia, Issue 17, [winter] 1991](fantazia17.jpg)

Welcome To Planet Clive

By Nick Griffiths, Fantazia, Issue 17, [winter] 1991

"I was reading a wonderful book by Susan Baur called 'The Dinosaur Man'. It's a documentary account of her encounters with

schizophrenics... The Dinosaur Man in the title is a guy who believes at least some of the time that he is a dinosaur. The

investigation of another state of being which is a response to the world is the kind of thing that I do, raised to or lowered to the level

of a disease. But I am not a victim of my imagining; they are tools, if you like. It's almost like the imagination is a number of ways to

pull on masks and look at the world through different sets of eyes. Well, what if one of the masks sticks, then the person inside

starts to wither and instead of being a person who wants to be a dinosaur when he chooses, he' s a Dinosaur Man? I think that

Edgar Allan Poe was very close to becoming a Dinosaur Man, rather than the man who played the dinosaurs. Keeping the balance

is very important.

"Keeping my mental health is very important to me. I am aware of the cracks in the wall that lie between what I know is real and

what I know is unreal. I don't think you can deal with this kind of material 14, 15 hours a day, every day of your life, without having

places in you which you worry about consuming you... I am very aware that I have the capacity for my imagination to use me as I've

been using my imagination. And perhaps my professional responsibility as an imaginer is one of the ways that I keep it under control."

Horrors! Here Comes Clive Barker, Monster-maker

By Dave Kuehls, The Plain Dealer Cleveland, 15 November 1991 (note - interview took place 30 October 1991)

"Basically I spent three years in horror. With the publication of Weaveworld in 1987, I was pursuing other things, namely the Clive Barker novel and the Clive Barker movie... It isn't horror; it isn't science fiction, and it isn't fantasy, it's a mingling of all these things and a bit more, too."

Dread Speaks With Clive Barker

By Michael Brown, Dread, No 3, December 1991

"I feel very comfortable being in a place where new age talk is

dinnertime talk instead of the kind of shame people in England feel

talking about God or reincarnation or psychic phenomena. This can reach,

of course, absurd proportions. You can have the kind of conversation

about personal growth in Los Angeles that would drive people crazy.

I'll tell you a true story. I had some problems with the pool I'm

having built. Two of the guys from the pool company came over and they

had fucked up in a major way. We were standing in the well they had

dug for my pool. One guy said, 'I sense a great anger in you.' And

I said, 'Yeah, I'm fucking angry. The pool is in the wrong place.'

And he said, 'I'm sure I'm speaking for my colleague when I say we don't

feel we can proceed if you feel anger. The vibrations are wrong, the

energies are wrong.' I said, 'The energies are wrong? Of course

they're wrong, the pool's in the wrong fucking place! I'm paying all

this money for this pool and it's in the wrong place. My energies are

really out of sorts about this, guys. They're really pissed off.'

They were shaking their heads about this and eventually said, 'We're

really uncomfortable.' I said, ' If you don't want to do this, if you

feel my energies are fucked, then get off the job.' Halfway through

this I said to myself, ' I can't believe I'm having this conversation.

This is so California that we should be having this conversation about

my energies. Give me a break.' "

Barker USA

By David Howe, Starburst Yearbook 1991/92, Special No 10

"There are a lot of weird little towns [in America] which are exactly alike - remember the town in Poltergeist? They are all built, as The Great and Secret Show's Palomo Grove is, on a system of several little villages with the mall, this shopping centre, in the middle. They are horrible, godless little places and are really eerie... They're entirely designed to be dormitory towns for Los Angeles. They're all built on the fault line and are full of these banal, grinning, cheery people who have got this fixed smile plastered across their faces. I found them all kind of spooky."

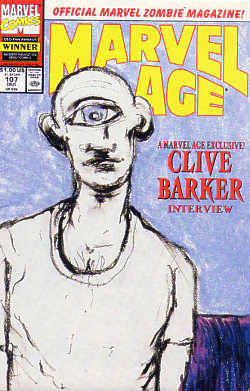

The Clive Barker Interview

By Mike Lackey, Marvel Age, No 107, December 1991 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

[Advice for aspiring writers] "Keep it simple. Trust your imagination. Discover what is unique about your imagination. Don't simply read a story and copy it. I go into myself. Then I transcribe what visions I have. If those ideas are original, and you are devoted, you will go far."

Click here for Interviews 1992...