Interviews 1992 (Part Two)

Clive Barker

By Kevin Proulx, Fear To The World, Studies In Literary Criticism #35, Starmont House, August 1992 (note: interview undertaken in 1989)

"Imaginative fiction is very often delving into the business of good and evil, angels, demons, the idea of heaven and hell. I think that, all the

time, one is using the vocabulary of theology. The theologians would probably be appalled that it's being used thus, but so be it. It's

a fiction about transformation, about transgression; maybe even about salvation. Those are the terms that would be as likely to come

from the lips of a priest as a writer...

"I suspect that if I live a full three-score years and ten, I may not like the idea of continuing into the everlasting, you know,

locked in myself. I'd rather throw my little sum of information into the bigger sea and embrace, in my terms, the information and

ideas which other people have gained over their lives. I wouldn't like the idea of continuing on forever just as Clive Barker."

The Interview From Hell

By Christian Gore, Film Threat, Volume 2, Issue 5, August 1992

"There's always been that sexual thing going on - subtextually, or in the first picture, textually. There is a much larger sexual quality to this one [Hellraiser III]. You go into cutting, blood-letting and orgasm here... In the six years since the first picture was made, ordinary sex is actually lethal sex. S&M is actually safe sex for everyone."

Horror In The Southland

Report on Horror Writers Of America convention 1992 by Sheldon Teitelbaum, Midnight Graffitti, No 7, Fall 1992

"I've always said if there is a thing to see, let's see

it. The best lovemaking is not in a darkened room, the

best fantasy does not occur in the mist. The best

writers of the fantastique say this is the mystery

plainly, this is the way the mystery looks, this is its

face, the number of eyes its got, the way it smells.

I've shown you this, be aware that the mystery is not

the way it looks but what the thing is. The point of

anxiety for me is that horror fiction is increasingly

divided from its underlying metaphysics. And no new

metaphysics has come to replace it. The old solutions,

which are basically Catholic solutions, or certainly

Judeo-Christian solutions, are still dragged in kicking

and screaming to solve a narrative. But those very

solutions are in doubt as to their efficacy in the real

world, not just among the writers but among the readers

too. There is a real issue here about what, if anything,

this stuff really means."

Mr. Horror: Clive Barker

By Andy Spletzer, The Stranger, Seattle, 7 - 13 September 1992

"I don't think you can write dark fantasy without desiring to answer some metaphysical questions. Dark fantasy comes out of a desire to find out what evil is, to explore the possibility of life after death, to address the notion of confronting God. In a book I wrote last year called Imajica, which comes out in paperback in a month's time, the hero discovers that he's the half-brother of Jesus Christ. He ends up confronting God himself. There's always, in what I do, this religious undertone. I didn't have a religious upbringing. Even though my mother is Italian and my father's Irish. I should be a Catholic. I'm not. I was maybe taken to the church once or twice in my childhood, no more. But I find the imagery of the Christian myth obsessively interesting. I have a six-foot crucifix mounted on the wall beside my desk. I suppose that goes some way into discovering or stating how interested I am in this body of potent tales."

Hellraiser III - Electronic Press Kit

By [ ], 4 September 1992

"Well, you know in the first movie we saw Pinhead as a force, a demon

raised from hell because of the solving of a puzzle-box. In the second

movie we discovered something about the man that he had been before he

had become Pinhead; the human being who had done the deal with the

Devil and become this soul-gathering monster as a consequence. At the

end of that movie the two halves of Pinhead - the human half and the

monster that he had become - were driven apart and as our third picture

begins, the husk of Pinhead, the thing which is the monster, which has

no moral qualms whatsoever any longer, is free on the earth, and that's

a fairly terrifying thought...

"In the third picture, we're actually creating not one, but a whole

host of Cenobites there - we've got a whole slew of creatures and that's

sort of fun because it means that the audience is gonna have the

central image, the central device of Pinhead there to give them pleasure

- and a little pain, of course - but they're also going to have a new

army, a sort of 'dirty half-dozen' of Cenobites to surprise them."

Clive Barker Explains Why Pinhead Will Never Go The Way Of Freddy Kreuger

By Elliot V. Meacham, Public News, 9 September 1992

"Freddy was scary because he was, at first, capable of doing something very cruel and then joking about it. I

think what happened to Freddy was that his cruelty became less convincing and the jokes became more dominant.

"Pinhead, however, is not a jokester and we are not going to turn him into one. That's why I'm constantly watching over these

characters. Pinhead is a much more intimidating and scarier character so it is difficult to get Pinhead to lower

himself to be a jokester - he doesn't have the seeds of that."

Pinhead Revisited

By Phantom of the movies, New York Daily News, 10 September 1992

"Freddy managed to be scary and funny at the same time but there's no way Pinhead can get away with that. He's got a couple of lines that are Oscar Wilde-styled witticisms, if you like, but basically Pinhead takes himself very seriously. I take him very seriously."

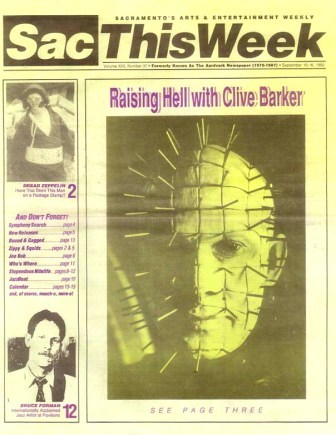

Raising Hell With Clive Barker

By Robert Farmer, Sac This Week, 10 - 16 September 1992

"The danger that one runs into with making sequels is that the tongue has a tendency to creep deeper and deeper

Sac This Week, 10 - 16 September 1992

into the cheek, so to speak. But I'm glad I was asked to oversee this film because I was able to voice my opinion, and they listened. I think that this movie has a lot of the stylish fun that one expects, but it is also in line with the serious nature of the first two movies...

"I'm always going to be writing. Books are a much more complex experience. They shape themselves to the individual, whereas with films, there is very little room for ambiguity... Writing will aways keep my heart. If I'm remembered as a writer who strayed for a bit into movies, I'll be happy with that. But if I'm remembered as the maker of Hellraiser who also wrote a few books, I'll be very disappointed."

The Man And The Myth

By Joe Leydon, Houston Post, 10 September 1992

"We're able to explore another rich vein of horror mythology here, and that's the sort of Jekyll and Hyde element that's

usually embodied in a single figure. Here, we've got the two elements separated. And I think the climax of having the

monster face to face with his alter ego - with the creature that's almost a man, who evoked him in the first place - is a

pretty neat idea. And one I think that the audience welcomes...

"What's interesting about Pinhead as a character - as distinct from Jason Voorhees, Michael Myers or Freddy Kreuger - is

that he has an agenda which is pseudo-metaphysical. He's much more interested in the souls of the individuals, and how

he can transmute them by his machinations, than he is in the simple business of slaughter.

"Of course, there is slaughter on the way to achieving his infernal ambitions but the interesting thing is that there's

a lot of talk of souls. There's a lot of talk of damnation. And judgement.

"It seems to me that one of the things that people go to horror movies for is to see that judgement in action. It's a

very primal satisfaction that's being offered up here. It's the satisfaction of seeing people judged for their wrongdoing.

It just so happens that the judge, the jury and the executioner are all embodied in that same individual - Pinhead."

Fiercely Imaginative Barker Has Serious Character Flaws

By Karen Hershenson, Contra Costa Times, 11 September 1992

"Part of the fun of the Hellraiser movies is that there is some mystery to these characters. Pinhead certainly exercises a very ambiguous charm. There are many people who are attracted to him... It's amazing the letters he gets... Doug is a married man and he's somewhat shocked at the number of people who think sleeping with Pinhead would be quite a thrill."

Barker Looks Forward To Raising A Little More Hell

By Tom Scanlon, Peninsula Times Tribune, 11 September 1992

"I am very fond of a quote of Dali: 'I am a drug, take me.' My mind works this way and always has... all the strangeness, perversity, surrealism - it's what comes naturally."

From The Mind Of Clive Barker

By Nicole Peradotto, Buffalo News, 11 September 1992

"Over and over, it's the confrontations with the great villains in books like Treasure Island, Pinocchio and The Wizard Of Oz that,

when you're a kid, give you a delicious combination of fear and pleasure. I'm not the only child I know who liked the 'Night On Bald Mountain' sequence in Fantasia. It's no accident there are as many dark passages as there are bright in Disney films, and it's no accident that those dark passages are the ones you remember.

"Thief is intended for my fans, but it's also a book that will be accessible to 10 year-olds, particularly if they're little 10 year-olds

like I was. Twisted."

Of Hell And Hollywood

By Ken Berg, (i) Orlando Sentinel, 11 September 1992, (ii) as 'Barker Keeping A Tighter Rein On Projects', Las Vegas Review-Journal, 12 September 1992, (iii) as 'A Bit Of Hell For Hollywood' [Knight Ridder], 1992

[After Nightbreed] "I've learned a lot about not being a passive film-maker, about not leaving decisions in the hands of people who maybe have another dozen movies to sell. Your baby is your baby and you have to take responsibility for it all the way along the line until it has met its audience and it's out on video."

Creator of 'Pinhead' Believes Imagination Is Key To Success

By Paul Jarvey, Telegram & Gazette Worcester, 11 September 1992

"I want to put my fingers in as many pies as possible. I've only got three score years and ten, I want to spread my imagination as wide as possible. My growing fascination with fantasy and children's fiction offers all kinds of new possibilities. I'm in my 40th year, and I think my brain is busier than it has ever been. I want to write historic fiction. I don't think you can expect any romances from Clive Barker. Beyond that, I feel as though the most an artist can ever do, whether you are writing or painting or making movies, is to chase your imagination. It's always a step ahead of you. My logical faculties are sluggish compared to my imaginative faculties. My imagination is telling me, 'hey, this is something we should be looking at.' I [chew] it over. Then and only then does sweet reason come in and tell me why I should be particularly interested in this area."

Clive Barker And The Horror Of It All

By Richard Harrington, The Washington Post, 11 September 1992

"All of us have these thoughts floating around, some of which will be defined as fantasy. That's the experience of consciousness, this shifting morass of

thoughts: 'Have I got enough food in the fridge?'...'When do I pay my taxes?'...'Boy, would I like to kill my boss.'...'Boy, would I like to make love to my secretary.'

"Then there's the wilder fantasy: 'Boy, would I like to fly to the stars.'...'What's it like on the dark side of the moon?' You also enjoy those sorts of thoughts.

Even people who describe themselves as very prosaic can entertain those thoughts in the downtime that they're thinking about the tax return and the mortgage.

It's always going on, it's part of the texture of our thoughts...

"We live on lots of levels. Just as our minds are this shifting collection of ideas, so we live on the level of trivial moment-to-moment necessities: 'I'm thirsty, I

have to get a drink of water.'...'I'm hungry, I have to eat.' And as we go down, it isn't a level of descending values, it's a level of ascending importance as we slip

into the unconscious towards those primal things - 'Why am I here?'...'What is the eternal part of me?'...'Do I have the capacity to perform magic?'...'Am I a good

person or a bad person?'...'Will I be damned?'...'Why am I out of it?' All those things are very fundamental questions... And those things seem to me to be awash

with very primal substances. It's the stuff of dream seas and blood and birth and corruption and pure, white light and profound darkness. In other words the visual

imagery which is the stuff of the deepest descent - those things have always been preoccupations with me... like my nerves were stripped to those things."

Hellraiser III Mixes Humor With Horror

By Cindy Pearlman, Chicago Sun-Times, 13 September 1992

"When you come out of Hellraiser III, you'll have a smile on your face, since the horror is funny. Coming out of Candyman, you'll need a stiff drink."

To Hell And Back

By John Wooley, Tulsa World, 13 September 1992

"It's kind of interesting - the first one was Chekhov, wasn't it? It was the family drama, played as a monster movie. The second

was the 'madhouse' movie, and then it moved into hell. The third one is urban. Again, if you've got a mythology, there are always

new ways to explore, new routes to explore.

"There are three Hellraiser movies now, enough for a Hellraiser all-nighter, and if you watch all three movies, if you put them all

side-by-side, there'll be no repetition, which is very important. If you put all the Friday the 13th pictures side-by-side, it would

become incredibly boring. Like halfway through the third picture, you'd say, 'Enough already.' Actually, I'd say it rather earlier.

I think in time you'd get bored with the Freddys too.

"The nice thing about seeing the Hellraiser movies side-by-side is that there's some sense of progress, some sense of a

narrative line that links them. Though they're completely different in style, all three will play very well together, I think."

Pinup Boy

By Michele Romero, Entertainment Weekly, 18 September 1992

[On Pinhead not having a singing role in the Motorhead Hellraiser video...] "I wouldn't want to hear this character's voice."

Sharpening His Pencils And His Pins

By Jane Sumner, The Dallas Morning News, 19 September 1992

"People raise their eyebrows that Clive Barker's writing children's

fiction, but many of the things which led me to dark fantasies

were seeds sown when I was very small. You look at Disney movies. There's a

large slice of darkness in the middle of those movies. The things that made impressions upon me when I was a kid were the dragon

from Sleeping Beauty or The Night on Bald Mountain sequence from Fantasia.

They completely etched themselves in my imagination in a way that the good

fairy never did. It's true for a lot of kids. If you ask kids what they remember, it's not

the three pastoral fairies. It's the dragon; it's the force of darkness.

"I've grown to adulthood, so now it's the Candyman stalking the ghettos of

Cabrini Green or it's Pinhead, the lead demon from the Hellraiser movies,

on the streets of New York. But the essence, the inspirational point, remains the same, if

you don't have fun with it, you shouldn't be doing it."

Hooked On Horror

By Hal Lipper, St Petersburg Times, 22 September 1992

"I have always been fascinated by sadomasochistic imagery and the ambiguity we feel toward the pain-pleasure threshold.

[In Hellraiser III] the bondage elements are back, those elements come up in my books all the time. But sadomasochism and

self-inflicted wounds and any sense that it might be pleasurable really pushes the wrong buttons as far as the film ratings board is

concerned.

"The function of horror movies is to create interesting, disturbing, bizarre, occasionally scary images. It isn't to provide cheap

laughs at the expense of the monster. In the case of Hellraiser III, I offer my imagination in terms of honing or adding a touch of

perversity, and to preserve Pinhead from any trace of self-parody."

Barker, More Than Just A 'Hellraiser'

By Tom Green, USA Today: Life, 24 September 1992

"The big man [Stephen King] goes his way, a force of nature. I'm never going to sell as many books as this guy. I'm too weird. I don't write about small-town America. I write edgy stuff with a lot of weird sexuality and strange political angles. Nobody's going to pick up Imajica in the airport and say, 'Oh, this'll be fun on my trip to Barcelona.' "

Horror Films Keep Creativity Alive

By Michael H. Price, St Petersburg Times, 30 September 1992

"While the market for horror has been weakened in recent years by bad video, still the fans remain loyal to the films that deliver the goods for them. Our Hellraiser pictures have been among those that deliver, and even if they don't break out to mass-audience acceptance, still they are being seen - and widely so - by people who make considerabledemands in terms of quality."

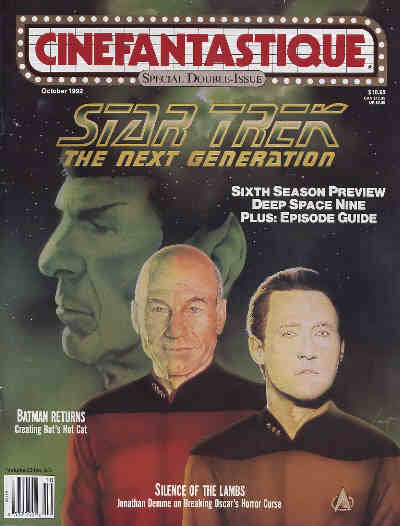

The Politics Of Hell

By Alan Jones, Cinefantastique, Vol 23 No 2/3, October 1992

"All monsters totter off into the the night on their own at some stage. Now it's happened to one of mine. Quite honestly, I'm not too concerned. It doesn't seem such a terrible thing to have happened. Peter [Atkins]'s script is spicy, contains some wonderful thrills and goes like a locomotive. Hellraiser III recalls the original's black perversity yet has been written on an extensive, intriguing canvas. Peter's grasp on what makes the myth work is very strong and I really have no cause for complaint."

The Devil's "Candy"

Editorial by Anthony Timpone, Fangoria, No 117, October 1992

"It would be interesting if someone put Hellraiser III and Candyman on a double bill. Both films came from the same mind, but they are completely different. There's room for both approaches, don't you think?"

Candyman : A Nightmare Sweet

By Daniel Schweiger, Fangoria, No 117, October 1992

"Candyman is less florid and baroque than Hellraiser. You don't have to believe in Lament Configurations to enter its world. Bernard has made something that's less supernatural and broader in its appeal. Though Candyman will be coming out at the same time as Hellraiser III, the two films couldn't be more different. Candyman is a new style of Barker, and it's going to be the scariest film of the year."

Clive Barker

By Anthony C. Ferrante, Pulse!, No 109, October 1992

"When people had me fixed as a horror writer, I gave up horror and turned to fantasy. Now that I'm established in people's heads as a fantasy writer, I'm moving into children's fiction. So I want to continue to move and change and surprise people. Plus, this [The Thief Of Always] is a classic crossover book. For the child it's an adventure about a house that seems to promise everything. To an adult, it's a story about the problems of time and childhood and what you give away in the moments of your youth you could never get again."

A Spinner Of (Horrorific) Tales

By Robert W. Welkos, Los Angeles Times, 11 October 1992

"When I was a kid, I had all kinds of experiences that have vanished

from my memory. People that I should have loved, people I

should have felt more for, who are gone. And education that flitted in

one ear and out the other. But did Jim Hawkins go away? Did 'Treasure

Island' go away? No, they stayed... Something that profoundly touches

the imagination carries more weight in your present mental geography than

things that actually happen to you.

"Let's suppose we are sitting in Ireland in 1901 and Yeats is telling

us about fairies and how much a part of his nation's identity and how

much a part of his poetic identity they are. Even

though [fairies] don't exist and they don't come into a room and have a

cup of tea with us, they become a more important part of our world than a

whole slew of events that may have occurred during that time."

An Honest Dollar's Worth Of Horror

By Laurence Chollet, The Record (Bergen County, NJ), 11 October 1992

"I'm very interested in stories, and storytelling - why we tell stories. Storytelling,

particularly horror storytelling, is very important in our culture - it's almost like we

need the comfort of something terrible happening down the road to give us the feeling

that our own lives are not so terrible - we haven't had our throats cut.

"Urban myths, legends, are a kind of storytelling, and that's what

I was exploring in 'The Forbidden.' It's a story about a woman who goes into this place

in a detached way, actually feeling sort of intellectually superior, to debunk the myth -

and the myth bites back. It refuses to be compliant."

Clive Wire

By Tom Crow, L.A. Village View, 16 October 1992

"Horror fiction works on lots of levels in different ways with different people. The threat of physical violence is at the heart of many horror movies. It's the heart of Frankenstein movies. What is he going to do? He's not going to talk people to death, he's going to twist their heads off. The threat of the monster is by and large a physical menace. Horror movies contain the theat of something that's going to do you terrible damage. That's the first necessity.

"The second necessity is that confrontations with the malign force have to be believable. They have to be logical within the reality system of the movie. It's like with the reality of scenes in the first Hellraiser movie. If you apply your rational skills to the situation it's nonsense. There's somebody being resurrected in the attic and demons coming through the walls. But the movie should evoke an atmosphere of dread, expectation and, possibly, excitement. The viewer ideally says, 'OK, I'm up for this. Give me your best shot.'"

Clive Barker Breathes Life Into The Horror Genre

By Stephen Hunter, The Baltimore Sun, 16 October 1992

"My enthusiasm lies in urgently passing the parameters of any thesis - to push the potential

as far as it can go. That's the attraction of fantastic writing: to be an exorcise medium for the

collective imagination. TV is full of banalities; politics is bankrupt. I want to go into other areas, to

examine the roots of our taboos and find out what's there. I believe there are fascinating, vibrant,

protean things...

"The melting-pot concept has led us astray. I've always been drawn to celebrate what is unique in

man, what makes him different from his brothers. I hate it when people try to be what they're not. You

have to be what you are."

Struck By Frightening

By David Kronke, (i) Los Angeles Daily News, 19 October 1992 (ii) The Baltimore Sun, 22 October 1992 (as Clive Barker Explores Life's Darker Side)

Los Angeles Daily News, 19 October 1992

"The only way to have any effect is to pass yourself off as something else. One of the reasons I'm writing children's fiction and

making pop movies is because I don't want to be discounted as one of the elite... I want to be a maker of stories for the

people. That means I don't get good reviews from The New York Times, but it does mean I'm getting to people who are at the

grass roots of the country. People who see Candyman are people who are not even interested in the [family values] debate that

we're having. But they will have something to bring away from the movie to think about. Hopefully, this [Thief of Always] will find its

way into nurseries across the country. That satisfies me deeply...

"I don't write scary books, I write weird books: you don't read my books and are scared in the way you are by a Stephen King book.

Stephen's dynamic is very clever - he takes people we feel very protective of and then puts them in situations of great jeopardy. I

take people who are kind of edgy in the first place and then put them in even edgier situations, where they very often find that

they're not as unhappy as they think they are.

"What in a Stephen King book would be some unspeakable terror, in my book they say, 'Ah. OK.' That's what Helen does

in Candyman. She discovers that her other life is far more banal, far more morally dead than the life - or death - that Candyman

offers. So her process is away from the warmth of the hearth, or the chill of the hearth, into something much more dangerous

and illusive and ambiguous."

The Candyman is Coming to Get You: Clive Barker

By Elias Stimac, Drama-Logue, 22-28 October 1992

"Stylistically, I don't think there could be much more radical a departure from Hellraiser III as Candyman. Hellraiser III

is a poppy, brightly coloured, special effects heavy gross-out, which I actually had a good time with - I think it's a fun

picture. Candyman is exactly the reverse of that, very low on special effects, very high on shock - I mean it makes people

jump a lot, which Hellraiser III didn't, and it's heavy on subtext, which is not what's going on in Hellraiser III.

"Vive la difference, I say! I love the fact that from material that originates in the same mind, pictures that are

stylistically so different can come. I've always loved variation. I think it's one of the things that makes life worth

living, the fact that there's new stuff always round the corner."

The Literature And Cinema Of Horror Are Two Interesting Ways To Celebrate Life

By Juan Rodrigues Flores, La Opinion, Panorama section, 23 October 1992 (note: translated from Spanish)

La Opinion, Panorama section, 23 October 1992

"I feel a great passion for the things that I do: the books I write and the movies that I produce and direct. I love the idea of trying to explore the soul of human beings. I am very pleased I have realized that I can write books on the complex perversities that are enclosed in any person. Something that always gives me great satisfaction when I see that I have succeeded, is to share with the readers of my books the passion I put in them when I'm writing them...

"For me, horror literature and films are, at the same time, two interesting ways to celebrate life, two powerful tools that can help us to transform the world. Perhaps for that reason, at the heart of the film and literature of terror there is something ambiguous and ambivalent. It is a combination that attracts and repels us at the same time. Good films and horror stories have this wonderful virtue."

Grisly Urban Legends Are Clive Barker's Inspiration

By Robert W. Welkos, Chicago Sun-Times, 23 October 1992

"The main thing is not to frighten people but to mesmerize them. What was it like to be in Jeffrey Dahmer's apartment? Now, we are disgusted by that. We are morally repulsed, but we are fascinated and we are liars if we don't admit to the fascination. Dahmer is basically a very pitiable character. Candyman...elevates you above the prosaic desires of a lonely man to collect body parts. It has a more elevated agenda. One of the healthiest things about a movie is that there is a total arc to the story. In the case of Candyman, the audience's point of identification, Helen Lyle, is a person with whom we can feel something. She is like us. She is not unnaturally courageous. She is someone we can relate to as an ordinary person."

Clive Barker Speaks After Candyman Screening At Mayer

By Mark D. Cappelletty, Los Angeles Loyolan, 28 October 1992

"To some extent, I write books and make movies to remind people that their imaginations belong to them. That the imaginative life is a very intimate and private matter, probably more intimate than what we do in bed, and should not be invaded by politicians, religious fanatics or even dare I say it, academics, because the academic fraternity also turns its nose up at this material very often...

"One of the bizarre things about my profession is that people can be very high-handed; you go to dinner parties and people say, 'Oh! You make those Hellraiser movies... Oh Christ.' But they get a few drinks inside them and a little later they come up to you and some say, 'I've got a funny story about our family...' and you become a sounding board for other people's weirdness. We've all got stuff in our heads; it's in every one of us. It's buried very deep inside us, but I think it's very healthy to let some of it fly."

CSN Spotlight: Clive Barker

By Cliff Biggers, Comic Shop News, No 279, 28 October 1992

"The Barkerverse postulates the existence of superheroes going back to the dawn of man. I am very keen to cast an intelligent backward glance over what

superheroes have been - and indeed, we can ignore the word 'super' and just focus on the word 'hero' for a moment, in the Joseph Campbell sense.

"One of the things which has always underpinned my horror and fantasy writings is the sense that the folkloric and fairy tale and mythological origins of this

material have their echoes in the stuff that we're all doing now. The image of the vampire in the horror story, the image of the superhero in the superhero comic,

they all have very elaborate traditions stretching back to the very beginning of storytelling. The notion of the great lizard, the blood-sucker, the hero who will save

us from the blood-sucker and the great lizards - these are actually a part of what we are as a species, I think. I love the fact that a very popular form like comic

books can have these echoes of much, much earlier forms of storytelling."

The Fabulist Of Terror

By Noah Cowan, Eye, 29 October 1992

"Although you see the image of death and the maiden running through all horror and film, we have to ask what she actually represents. Quite simply, she represents life because she is a baby maker. That absolute image of beauty and fecundity is then fixed upon by its opposite - decay and destruction. This works out on a mythological level that transcends horror entirely.

"But I am very even-handed about destruction in my films. When women die, men die. And women are usually the central figures - it is they who discover transcendence, who come into their own. I think in Hellraiser III and Candyman, women are getting something that doesn't represent their sex as stupid fodder. So, although the female protagonists behave in dangerous ways, they do so for legitimate reasons. They are rational and intelligent, and their behaviour is at the heart of the film."

The Vault Of Horror

The Vault Of Horror, BBC2, 31 October 1992

"We go to horror movies to see the villain at work. We go to see Dracula, we don't go to

see Van Helsing, yeah?  At the same time as wishing him to be depraved - demanding him to be depraved, being entertained by his

depravities - we are, at the same time, watching in the full and certain knowledge that he will be dispatched. The

Devil is allowed to play all his best tunes and we can dance to them for a while and then know that the pipe will

be put down and that good will come in and we'll be led out to a clear, white dawn..."

At the same time as wishing him to be depraved - demanding him to be depraved, being entertained by his

depravities - we are, at the same time, watching in the full and certain knowledge that he will be dispatched. The

Devil is allowed to play all his best tunes and we can dance to them for a while and then know that the pipe will

be put down and that good will come in and we'll be led out to a clear, white dawn..."

Why Mr Horror Is Still Going To Hell

By Peter Grant, Liverpool Echo, November 1992

"I may have physically left Liverpool, but I am here in my stories. I often dream about the place. In fact, I have a small light mark on my hand that I got when I impaled it on a stick near Penny Lane. It brings back memories every time I see it...

"Mum and Dad brought me some prints of the city and now I've got a view of home... from home... at home. I have the whole family there in print right back to my grandfathers...

"A few of us were sitting around the swimming pool in LA and we were talking about Liverpool. It's true - here I am in a 1920s house and yet at one time I was on the dole. It can be done - we all have to take the right road, the road we believe in."

Opening The (Puzzle) Box Of Delights

By [ ], Comic World, No 9, November 1992

"Morte Mamme was first defeated by Cenobites many, many, many years ago,

and has been buried alive. But she sends out waves of power to bring

a new series of Harrowers under her control, and through their eyes we

will learn a lot more about the way Hell works.

"I think part of the problem is that basically, with few exceptions,

once a human being gets in the company of a Cenobite that's it. There

may be a few twists and turns, but by and large the Devil always wins,

so you never get to investigate the mythology very far because you're

always feeling with the human perspective, which is very limited. It's

a cul-de-sac. Now, finally, we have human beings who are going to

enter this world, the world of Hell, and deal with the Cenobites in a

significant way. I think that's going to be a very interesting battle

because at the same time as serving the desire to make chilling

narratives, I think we're also going to allow a kind of weakness and

humanity into the narratives."

Pulling Away The Veils

By Stan Nicholls, (i) Writers' Monthly, Vol 9 No 2, November 1992 (ii) re-edited and slightly extended as A Strange Kind Of Believer, Million, No 13, January - February 1993 (iii) in Wordsmiths Of Wonder by Stan Nicholls, 1993

"The worlds which open up in Imajica, just in terms of

their physical scale, not to mention their metaphysical

scale, are so much larger than I would have dared

attempt even a couple of years ago. My readers, and

they number in their hundreds of thousands, are very

glad that they have more than the shock tactics to

engage them through an 850-page book. And remember,

the horror, the darkness, has never gone. Imajica has

still got some very dark passages in it. So have The

Great And Secret Show and Weaveworld.What's been added

is this, hopefully, transcendental level.

"What's also been added is a sense of thoroughly created worlds; I

mean worlds with names, tribes, flora and fauna,

religions, cults and so on. I did hint at dimensions

hidden in secret places in the horror fiction,

obviously, and a lot of it contains the sense that if

you open the wrong door you're going to find yourself

lost in another world. The way I'm doing it now, it's

not just opening the door but knocking down the whole

damn wall and saying, 'Here it all is.' The readership, I

think, is very excited by that prospect."

Evil Not Just A Fantasy For Horror Master

By Chauncey Mabe, South Florida Sun-Sentinel, 15 November 1992

"I believe in this stuff. I believe in magic. I believe that we have an essential

divinity and an essential demoniacal quality as human beings. We should not be afraid of

these things.

"Many of my contemporaries in horror and fantasy fiction don`t believe. They tell damned

good stories, but the difference between my work and theirs may be that what comes from

me is the conviction that these stories and images are metaphors for real states of mind."

Barker Writes On The Wild Side

By Michael Blowen, The Boston Globe, 17 November 1992

"I like to stay busy, I was born to work but by working I have fun..

"People are surprised, but the roots of my books and movies are in the dark fantasies of childhood. Disney turned it

into an industry. The Thief of Always isn't a children's book in the traditional sense. It's not for kids who are used

to tamer books."

Satanic Writes

By Craig McLean, Scotland On Sunday, 29 November 1992

"My passion is for imaginative work of one kind or another. I've written epic horror, I've written epic fantasy, I've written sexual stuff. Now this book offers another area I want to explore. I've never defined myself as a horror author. I see myself as an imaginer. And The Thief Of Always is another piece of imagining.

"The Thief Of Always is a lighter experience, both in the experiencing by the reader and in the writing. But it also has its resonances, like in fairy-tales. There are worlds within worlds, things hidden away. I think that's satisfying when you discover that you can find simple forms of stories that have richness that you don't at first anticipate.

"It is short, with nice pictures, 'drawn by the man himself,' and moves along at a fair clip. And I'm hoping that there will be readers who come to this book and open it and enter its worlds more readily than maybe they would have done with Weaveworld or Imajica; and then in turn they'll be led on to those books."

In The Flesh

By Michael Brown, (i) Dread, No 8, 1992 (ii) quoted in Fine Cast Enlivens This Obscure Fable by Julie York Coppens, Charlotte Observer, 12 November 2005

"I am a Jungian, not a Freudian. I believe that the

collective unconscious - a pool of shared images and

stories which all humanity is heir to - exists, and that

the artist dealing in the fantastique is uniquely

placed, in that he or she can create stories or

paintings which dramatise the eruption of the

unconscious into our day to day lives.

"I've pointed out many times that we spend one-third of our lives

asleep. During the adventure of dreaming, we are making

both a private investigation into our hopes and fears

and also swimming in the dream pool which we share with

the rest of our species.

"I hope that the fiction I

write will empower us to both comprehend our secret

dream and understand the profound intimacy we share

with every other human being."

A Conversation With Clive Barker

By Tyson Blue, Cemetery Dance, Vol 4 No 1, Winter 1992

"I think the problem with commercial fiction is that it's become kind of soulless, in a way. I know that there are a lot of writers writing science fiction, writing horror fiction, writing fantasy fiction, who are writing things they don't even believe. Now I don't mean believe in the sense that I believe Cenobites really exists, I don't. But I do believe that the moral and philosophical underpinnings of my books are things that I would defend in an argument."

Harvey, A Fantasy Hero For The '90s

By [ ], HarperCollins Life, No 5, December 1992

"Peter Pan was my inspiration; Peter Pan was the first great love of my life. It works on many levels. Pan touches people in different ways and it means something different to you if you read it at eighteen than it did when you read

HarperCollins Life, No 5, December 1992

it at eight.

"I think The Thief of Always is the same. It, too, has many nuances, and will mean something entirely different to a young person than an older person experiencing the passing of time.

"It has as its hero a ten-year-old boy, Harvey, who is just as complex and resolute as some of the adults who read my other books. Harvey finds himself in a magic house where every day he experiences is all the four seasons of a year... in fact each day is a year in the world outside.

"It is a scary book touched by the real life issues of life and death. Part of the pleasure of writing The Thief of Always was to evoke all the emotions of being a child again - the despair when you just want to die, the elation that makes you float. I can remember those childhood feelings. Most people can. We never lose the dreaming child within us, it may wander away sometimes but it is always there."

Clive Barker

Transcript of a talk at Kepler's Books, Menlo Park, California, 2 December 1992

"Yesterday, I was in Denver and I went to speak to a class of some

fifty students, maybe ranging in ages from 11 through 15, to talk to

them about creativity. Basically, they wanted to hear about the

movies and books and so on...

"I said, what little you know of me, you should know that my imagination

is fairly wild and much of what I get, I get from dreams. We

started to talk about dreams and all of them started to pour out these

angst-ridden tales of dismemberment and drowning and physical transformation -

little 11 year olds. And the members of staff who, up until this time,

hadn't seen their little charges speak this way, were aghast,

their jaws were hanging open hearing it. 'Oh, yeah, sometimes I wake

up,' one sweet little girl said, 'I wake up feeling there's this

spike all the way through my chest' - don't ask, don't ask, but

certainly Freudian - 'all the way through my chest, protruding out a

good six inches.' Protruding six inches, imagine! So she had this

imagining, very graphic. Something that came up over and over again.

"It was interesting, because we all have these things and as

kids we all have them buzzing around our heads all the time and finding

ways to articulate them is difficult."

Video World, Festive, December 1992

Video World Classic : Nightbreed

By [ ], Video World, Festive, December 1992

"Nightbreed was an incredible challenge from the very beginning. Chris Figg, the producer of the Hellraiser movies was sacked from the project six weeks in, and then my executive producer Joe Roth became the head of 20th Century Fox. Nightbreed was just one small movie on a whole list that Fox were releasing and Roth didn't want to be seen to be playing any favourites, so he almost wilfully distanced himself from the picture.

"Next they put out what was probably the worst ad campaign known to man. David Cronenberg actually wrote to Fox saying, 'How dare you do this to our movie?' Of course in the end it didn't do anywhere near as well as we expected. In fact it ended up being pretty much of a disaster at the box office."

Sweet Talking Guy

By Simon Bacal, Shivers, No 4, December 1992

"When Bernard [Rose] came to me with thoughts, observations and anxieties, I always tried to give him the benefit of my opinion. I felt it important to be very supportive towards Bernard. I wanted him to feel the film reflected his own true vision, not mine. But during the test preview process, there was some question as to how the film ['Candyman'] should end. While I don't feel audiences' wishes should be accomodated too much, I encouraged Bernard to put back the original ending he'd written. And now it works very well indeed."

The Heights And Depths Of Hellraiser

By Douglas E Winter,

(i) Fangoria, No 119, December 1992

(ii) Fangoria : Masters of the Dark

"I hadn't shot an inch of celluloid and no-one was going to throw a large-scale budget at me - and I didn't want one. I mean, If I am going to screw up, I want to screw up on a low budget!"

Professional Imaginer Clive Barker's Eclectic Talents Defy Pigeonholing

By John Marshall, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 8 December 1992

"Best-sellerdom is dominated by repetition; to be a brand-name author, you do what you did before with a minimum of change, but

in my books, I like to prove I can fly off in different directions. My imagination leads me to do what makes sense to it. My imagination

is my polestar; I steer by that.

"I'm not the Stephen King of the '90s - that's not what I am; I'm not the future of horror, either. I'm Clive Barker, a guy who's

imagination flies off in different directions. I'm a professional imaginer, with work that ranges from very visceral, down-and-dirty horror

to erotic material to fables to stuff about angels. If that seems like an eclectic bunch of things to have done, it all comes from the

same space in my brain. I see myself as someone who speaks out of his imagination and trusts it...

"I would hope my work isn't harmless fun; I would be very disappointed if people considered it that. I take this very seriously. This is

metaphor, an examination of what's dissolved in the subconscious, which is then reconfigured in various ways by every reader. This

is part of the tradition of fantastique, work with a layered quality, meaning different things to different people. It is work with

resonance."

L A Gore

By Paul Mungo, GQ, December 1992

"My major bad habit is work. I've always got five projects going."

This Man Will Give You The Creeps

By Christie Hickman, Midweek, 10 December 1992

"The imagination that delivers you into the dark places is the same mechanism that delivers you into fairyland. Many images in kids' books are very dark and

surreal and disturbing, and those were always the images that I and my friends took pleasure in when we were young. I think children love taboo; the stuff just

behind the veil. If you go to a Disney movie, there is always some darkness. The point is that there should be triumph over the darkness...

"One of the wonderful things about the fantastique is that every possibility should be addressed and celebrated. It should be a genre that opens every door, when

so often it is a genre which concerns itself with closing doors completely. If fantasy is to come of age, and I believe that it is still finding new forms, then it has to

say: 'What does the adult imagination do when it is blocked in every way by the mortgage and the tax return and the whole business of nine-to-five? How can the

imagination fly? And how does the fantasy, having taken you for the flight, deliver you back into that blocked place when you're eager to find ways out?' At its

best, it seems to me that fantasy is confrontation and explanation and exploration, not escape, because it offers parables for being, not ways to sort of erase

yourself.

"One of the wonderful things about the fantastique is that every possibility should be addressed and celebrated. It should be a genre that opens every door, when

so often it is a genre which concerns itself with closing doors completely. If fantasy is to come of age, and I believe that it is still finding new forms, then it has to

say: 'What does the adult imagination do when it is blocked in every way by the mortgage and the tax return and the whole business of nine-to-five? How can the

imagination fly? And how does the fantasy, having taken you for the flight, deliver you back into that blocked place when you're eager to find ways out?' At its

best, it seems to me that fantasy is confrontation and explanation and exploration, not escape, because it offers parables for being, not ways to sort of erase

yourself.

"It's impossible for me to speak of what I do without straying into metaphysics, because it's why I do what I do. I think escapism is the denial of reality. In a

different way to Stephen Hawking but in a parallel way, I'm doing what he's doing with the mathematics of my imagination what he's doing with the mathematics

of equations and higher physics. That's saying: 'We know so little, but the doors are open on every side and we don't even see them'. Imagination, you know, is

eternal delight."

The Road To Hell

By Dave Hughes, State, Issue 3 Vol 1, December 1992 - January 1993

"[My involvement in Candyman] was that of a very present executive producer, and somebody who developed the material with Bernard so that it made cinematic sense. So it's a picture I feel particularly wedded to because I was there from word one. I'm certainly not passive about movies. If I'm there at the dailies, I have views and I voice them. But I also think it's very important, having been beaten up by producers in my own time, to let the director do what he wants to do, because that's who you've hired."

Lock Up The Kids - Horror Titan Clive Barker Unleashes A Children's Fable

By Sean Piccoli, The Washington Times, 16 December 1992

"For the 10-year-old who reads Thief of Always, it is, I think, an adventure primarily. It is about a child who has time

stolen from him and revenges himself royally upon the power that steals from him.

"I would defend to the death the moral care with which Thief of Always has been written. This is not a casually anarchic book.

It's a book... the author of which believes totally in the underlying morality of the fiction...

"Once you become an adult, it becomes your responsibility... to stop children fudging the line between fantasy and reality... to

remind them that life is about the hard realities of the tax return and the mortgage, when in actual fact we know in our hearts that the

tax return and the mortgage will turn to dust just the same way we will, but that the life of our soul, the dream life of our soul, is

accessed to - the eternal."