On The Way To Heaven, We Had A Picnic Of Ideas...

The Thirty-Fifth Revelatory Interview

By Phil & Sarah Stokes, 10 November 2020

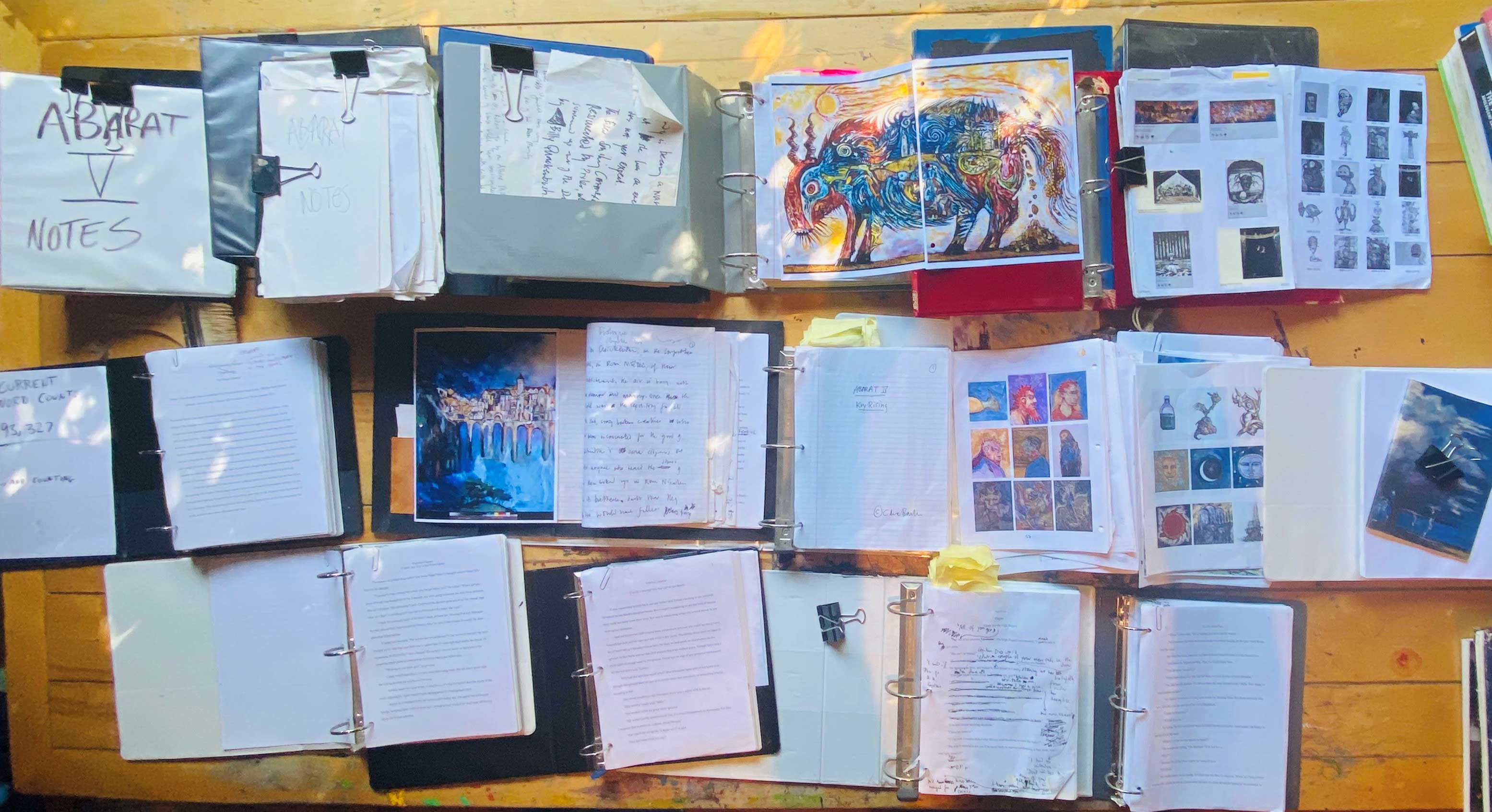

Ahead of the conversation below, Clive had laid out the folders of current drafts of Abarats Four and Five on his desk and sent

a couple of photos across to us to share a view of his Abaratian progress. We talked about a few plot points which we've had to

remove from the text below for now, but will add back in here once the books are published.He'd also sent us the final draft of a new novel, Mercy and The Jackal, which he's written for inclusion in a fiction collection to be called Fear Eternal. Again, we'll add back in the spoiler narrative points we discussed here as soon as the book is published.

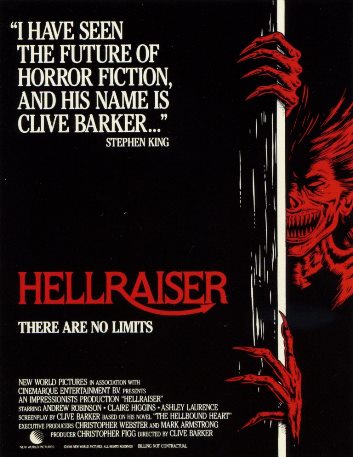

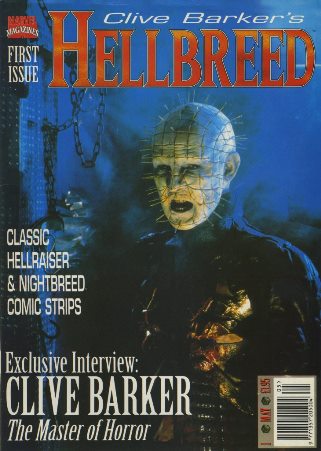

Revelations : "The announcement at the end of last month that you might be actively involved in a new Hellraiser TV show attracted a lot of excitement – what can we tell people?"

Clive : "Well, you know, who knows? But it looks plausible. I mean I don’t know… I just don’t know anymore. There’s a lot of things going on and the struggle for control over the thing is what concerns me. I have lots and lots of ideas about what we might do with the Hellraiser narrative on television and the question is how much – I don’t want to use the word power, I don’t even want to use the word authority – how much sharing I will be able to do because there’s a lot of people engaged on this project, most of whom I don’t know … I may as well just confess this, I’m betwixt and between. Part of me says, you know, I originated this, and for the last 25 years not a month has gone by without me thinking of something I want to do with it. Meanwhile, a bunch of other people who I haven’t known have been making movies, using the mythology, and I sort of want to go back to basics, I want to go back to those first two or three movies and look at what worked and use those as a jumping-off place for some really, really dark, wickedly perverse narratives, and the question is how much freedom they will allow me to have to do that and I simply don’t know.

"It won’t be for want of trying if I can’t do it, I will try my damnedest, I certainly will, just because I feel – and it’s stupid to say – possessive of it, but I feel I know a lot of things about those narratives and those characters that I’ve never been able to share and so there are some really, I think, mind-blowing ideas I have which come from almost meditating on this narrative for almost three decades."

Revelations : "This is not the first time anyone’s come to you and said, well, come on, Clive, let’s go do this, let’s grab this by the scruff of the neck and take it for a ride again."

Clive : "You’re right – I think, as a consequence of that, Sarah, I feel it would be naïve of me to assume that this situation will be any different to the previous disappointments – and by disappointments I mean, and I can’t exactly explain why this happens but it happens in Hollywood all the time, the originators of ideas are the first ones tossed off the boat - I don’t need to instance the number of people to whom that has happened, it’s endemic. I think it comes from two things: I think it comes from finances, obviously – if you have a successful something and it’s made money, then other people jump on board because they want to make money; but I also think – and I think this is way more distressing – people want to steal the glory of having originated something even though they didn’t."

Revelations : "Perhaps the people with ideas, the people who originate ideas, are often the first to go because ideas are dangerous..."

Clive : "Could we just go with that for a moment? I have had wonderful experiences, wonderful collaborations in cinema, really tremendous. But it’s very often the people who are not actually creatives who cause the problems. I had a wonderful relationship with Bernard Rose, wonderful collaborations with actors and with make-up people, and you know, designers: Steve Hardie and obviously Bob Keen on all the Hellraiser stuff and indeed Nightbreed. The people who put their fingers in the pie – and very often they’re dirty fingers – to steal the pie, are people who don’t have an original idea in their heads but envy, I think, creativity. I sort of think that God gives you the creativity: you’re born with it or you’re not, you can’t learn it and you can’t steal it because what happens very often is that people say, oh, I’m taking this over, and the results are either shit or halfway through they yell at you to come over and help and that’s happened a lot and I can’t do that and I can’t forgive people who do that to me. Maybe that’s petty but I can’t."

Revelations : "We’ve talked before about how creativity is a kind of magic to anyone who can’t do it themselves – as you would say about media you don’t work in, I mean you find music magical."

Clive : "Music is magic, for sure, I mean, God, to be able to put a tune together and write it down in a kind of code on a piece of paper – so that somebody can pick up a flute or a trombone or whatever the hell it is, or sing, and turn that into something that makes me cry – it’s magic. The only time I can ever write music is in dreams. The thing I can’t do, I do in dreams, passionately, and I wake up with a fucking symphony going on and then, of course, it’s all gone... I’m a great Sibelius fan and so I usually find I’ve ripped off Sibelius in my dream version but what are you going to do?

"I’ve been granted by creation – creators – the access to a number of processes, you know, writing plays and movies and painting and stuff and of course the things you’re always envious of are the ones you can’t do! And so it would be cruel of me in a way to say that I don’t identify with people who want a piece of whatever I’m making, it’s just that very often in their eagerness to possess it they can be very cruel."

Revelations : "With Hellraiser, you have revisited the mythology on a couple of occasions."

Clive : "I have."

Revelations : "As well as the couple of treatments you wrote for Hellraiser movies that didn’t get made, you’ve had a hand in some of the storylines for comics: it’s like you’ve been looking for the right route back into it..."

Clive : "I think that’s exactly right, Phil, the route back in that means I don’t waste a year of my time, coming up with a disappointment. I am sixty-eight, I don’t have time to waste playing political games with people who are going to win because, in the immortal words of Jim Robinson of Morgan Creek, ‘I believe in the Golden Rule: I have the gold, so I make the rules.’ It’s horribly plain, isn’t it? So I feel very covetous of my time now – ‘now’ being at the wrong end of life, if you will – to be as filled with ideas as I presently feel. There’s so much I want to do and I suppose one expects to die with too many ideas: that would be a good way to go."

Revelations : "Take some with you for the journey, Clive."

Clive : "Exactly right. Put them in sandwiches, you know, and get a flask of ideas to go with them."

Revelations : "That’s a very English idea!"

Clive : "It is, isn’t it? A picnic of ideas along the way: ‘On the way to Heaven we had a picnic...’"

Revelations : "When it was announced that you were getting involved in the Hellraiser TV project, reaction seemed to split into two: one was, ‘brilliant, that’s going to make Hellraiser as a series great’ and the other was, ‘yeah, great, but I’d rather see Weaveworld, or Imajica, or The Great and Secret Show…’"

Clive : "So would I!"

Revelations : "Do you think that the time has come for television and Clive Barker?"

Clive : "That’s the big one, isn’t it, that’s the $64,000 question. I have no clue. The future will tell, I think Phil. If I’ve learned anything from having been involved in a number of different media it’s that none of them are that predictable. You know: Thief of Always they wouldn’t publish, so they bought it for a buck or whatever; when I turned in Weaveworld there was a moment of disappointment that it wasn’t a horror book; Imajica was, ‘oh wait, there’s something that changes sex...’; and Sacrament was, ‘Oh... wait...’! I mean there’s so many stories that I have told or shared with you, and I’m sure you’ve shared with others about the fact that almost nothing I make gets a universal thumbs up because it’s likely to be different from the thing I made last time."

Revelations : "It’s because it’s got ‘ideas’."

Clive : "Well let me go one step further, if I may, and say an idea which isn’t like the the previous idea."

Revelations : "Yes, that’s what I mean, one that will need fresh thought as to how to market it."

Clive : "Yes but readers are so much smarter than publishers. Readers – my readers – have accepted with open arms almost everything I have brought to them and it’s one of the reasons why I love them, it’s one of the reasons why it’s wonderful still to go to conventions, because there are people of every conceivable age, shape, size, ethnicity and sexual passion, who will line up and tell me something different each time about what they like. It’s interesting because you probably see more of that than I do, that diversity of enthusiasms, if I can put it that way, yeah? I don’t know whether this is true, this is probably hyperbole, but it seems to me that no two people like quite the same combination of things that I do, even me. And you know that to be true, I’m sure, because I went through the eight books of Imaginer three days ago and there’s no, I suppose you could say, cogency: there’s no stylistic or imagistic or flavour or tone that is consistent from page to page. Even when they all belong in the Abaratian books, they’re different: some are comical and broad, some are very, very dark, some are long-shots, some are close-ups.

"Diversity has always been my thing and I think it goes along with my lack of patience. I’ve never been a very patient person – except when I’m a patient… when I’m curiously patient. When I went to hospital last, and the surgeon came along and looked at my foot and said, ‘we need to do something to this within two days or you’re dead’ – it was a Tuesday and he said ‘we have to do this before Thursday’ – and then he got a scalpel and he just cut my foot open while I was lying in bed, no anaesthetic no nothing, just a bucket underneath the foot and Roman looked at me and I think he was thinking why aren’t you screaming blue murder and the answer was when people are doing something good for me – and I assumed the best – then you put up with it, you’re patient. When I’m doing it for myself I’m impatient. I know that’s a terrible pun but it’s the patience of the patient...

"I’m going through the drawings right now, and I suppose there’s about 5,000 right now piled up. I went through about 400 last night and I can remember doing none of them... I mean that’s literally true. Now I don’t know if that’s of interest to us or to the people who are reading this as to why that is but I don’t remember these things – why not? Do you think most artists are like that?"

Revelations : "It contrasts with everything you say about the canvases where you do remember, and I know they take longer while your sketches are..."

Clive : "Very fast."

Revelations : "...almost idle doodles as you’re doing something else."

Clive : "Yes, my Dad did it on the phone book, he covered the phone book with doodles like that."

Revelations : "I don’t think he doodled the kind of things that you draw!"

Clive : "No, I think that’s probably right, they mostly looked like Popeye. I’ll send you a few of the sketches I discovered last night and you’ll see. I found last night, for example, Abarat as a six-pointed star, have I shown you that? I will send it to you before the day is out. I think there’s some fun things but what I was actually doing was going through the 400 / 500 drawings to find monsters for a project I’m talking with some good folks about doing together.

"What you say is right, Phil, when it comes to the oil paintings I do remember. Oil paintings are very labour intensive, a very fluid experience – I spoke with Brannon Braga two or three days ago about painting – Brannon said he’d only made one oil painting in his life, when he was sixteen, and I said, ‘why only one?’ and he said ‘I couldn’t stand oils,’ I said ‘why,’ and he said ‘because they keep changing’ and they do, I mean, you’ve watched me paint and oils are protean, yeah? One of the things I would say is that I do remember – not always – but I do remember painting the oils but if you look closely at some of the oils you’ll see there’s another painting behind it, you can see the lines, you can see the scrawls – I don’t remember that painting, you know!

"It’s certainly worth a conversation at some point as to why... let me go another way... I don’t have a clue as to the feelings I was having when I was writing the books simply because they’re too... well it takes three years to write a book like Imajica."

Revelations : "Although you’ve been very clear about how you felt as you completed the last draft of Imajica."

Clive : "What I would say, Sarah, is that I was about to say that very thing: I remember the feelings that are associated with concluding a narrative; but if you were to ask me what Dowd is doing on page 340, I wouldn’t have a clue! Resolutions to narratives move me if they’re working and it’s almost a test as to whether a narrative is working, if I am dry-eyed or crying at the end of the narrative.

"I remember going to Harper and somebody had just read Thief of Always and this man – I won’t name him – said, ‘I hate the ending, just the last paragraph, so I’ve redrafted it for you,’ and he passed me his draft and I won’t comment but, he was a nice man too, he just didn’t get it at all. It took me a day to write that last paragraph and if you look at that last paragraph you can see why it took a day, because I was going through seasons and I was going through feelings – is the book there?"

Revelations : "Sure:

Clive : "Love enough for a thousand Christmases... yeah... Everything that is in the book is in what you just read, Phil – every nuance of feeling that is in the book is not just that last sentence but the fact that it is about being separated from your parents, being given a second chance. It’s a redemptive book, I think, and I know as a kid you don’t think about redemption but I think that’s one of the reasons why the book works for adults as well as kids."

Revelations : "You don’t think about redemption as a child, but you’re very familiar with doing wrong, and with forgiveness."

Clive : "Very true, very true, and you’re also I think very aware of loss – what lad does not remember the first pet they lost? I remember my Mum coming in through the front door with the body of Kemis our dog in her arms and I suppose I must have been, I don’t know, six? Animals teach us so many things and think that one of the things I haven’t done yet and so desperately want to do is write about animals and their impact on my life – I don’t just mean the animals I live with but the animals who I see in a David Attenborough programme or the animals that at this present moment in our planet’s dangerous time we may need to mourn, you know.

"Sacrament began with seeing a film of a polar bear with a mayonnaise jar stuck on his nose and that appears in the book, that image, and that was what it was about. It was about the fact that the receding ice sheet was obliging those polar bears to go to extreme ends to find nourishment and it’s a polar bear that starts the entire story in a way, you know, Will almost dies at the paws of a polar bear. That had an influence on me, on my feelings about dangerous animals. We’re killing everything. I mean it seems to me… I can’t watch David Attenborough programmes any longer: he’s obliged, because he’s an honest reporter and observer, he’s obliged to give us the falling note. He cannot, rightly so, make a programme which is pure celebration."

Revelations : "So many of these things now touch on human behaviour so you can’t not talk about the plastics in the sea, you can’t not talk about the effect of beef cattle."

Clive : "Right, and you can’t help but say these things will not be here in twenty years. Joseph Steep from Sacrament is obsessed with observing the last of things and I don’t know whether that book works – I think it works in places and perhaps not in others – but Steep and Rosa were intended to be the Macbeths but I couldn’t do it, I didn’t have the commitment to that villainy. They – it’s silly to say I forgave them, it wasn’t anything like that, they forgave themselves, I suppose, the narrative forgave them when you realise they are not Nilotic they are a singularity. When you meet Rukenau and all that stuff at the end, you know, what is that part called, He Enters the House of The World, is that how the part is titled – Domus Mundi, right? – a part of me realised that the book could be twice as long. When I got into Domus Mundi I was confronted with something that I’d never been confronted with before – that there was another subject waiting for me, which was the state of the world, and I wasn’t going to be able to address it without doubling the length of the book and it had sort of wiped me out anyway. And then of course we still had the troubles to come when they said, ‘oh wait a second, there’s a homosexual in this book...,’ and all that stuff went on.

"Sometimes my books feel like pieces of a much bigger thing and I’ve never said this at all to anybody but I think they’re all one story."

Revelations : "Do you know what the story is?"

Clive : "It’s, ‘living and dying we feed the fire.’"

Revelations : "As you know from the Memory, Prophecy and Fantasy books, we’ve always been fascinated by the through-lines, the recurring themes."

Clive : "Yes."

Revelations : "When you say you haven’t written about animals yet, I think you’ve written about animals and their place in your life but you clearly have more to say. But if I look at something like the variegation of the flora and fauna in Imajica or I look into some of the islands of the Abarat or I take it even into Nightbreed when you had such variegation – what did you call it – A Hymn to the Monstrous?"

Clive : "I think you’re right, you know the last person who should – as at one point one of the characters in one of the books says – don’t ask me to explain, I’m just the artist. I don’t have a clue what I’m really up to except that once in a while I see connections: you both pointed out when you were reading the draft of Mercy and The Jackal that it is thematically and even structurally to some extent the same as an unpublished story of mine, The Knight and The Demon, right? And I’ve been puzzling about that since you said it because of course, it’s true... and they're both a different style for me... what the hell was I up to? I realised, though, how much Calvino is in Mercy and The Jackal, particularly Invisible Cities. I don’t know if that’s a book you’re familiar with?"

Revelations : "Yes, I haven’t read it for a long time but I studied it at some point."

Clive : "Gotcha. Well that’s bound to wipe it out of your memory! That idea that there really is no through-line to the narrative, except the subject. You know, in Invisible Cities, Kublai Khan and Marco Polo are having a conversation and from that comes a series of brilliantly formulated two- or three-page summaries of cities, yes? And I think that the structural profligacy of Mercy and The Jackal, I learned from Calvino. I think that idea that he tells a narrative like nobody else does – Borges tells another kind of structural narrative. Neither of them are like, let’s say, English writers."

Revelations : "No, it’s just a whole different tradition."

Clive : "It is, but I wonder if it’s even a tradition or whether it’s a singularity, if it’s Borgesian or if it’s Calvinosian… I mean the man died at 61/62 and he had so much more. Borges of course lived to a fine old age. I happened to pick up Invisible Cities just by accident, by good fortune and, wow! I must have been thinking about this when I was writing Mercy and The Jackal. I don’t know if that’s right or not, you know, I’m absolutely open for comment or instruction as an observation by the author but I’m still puzzling over Mercy and The Jackal, in a good way."

Revelations : "There’s certainly a freedom you’ve given yourself in it; that it doesn’t go from A to Z, it doesn’t follow the normal beats of a narrative structure."

Clive : "Not at all."

Revelations : "You had the freedom to follow your nose effectively but say, ‘hold on, that reminds me of so and so – what are they doing – so let’s go back to them’ without a sense that you’re doing it on purpose, that you’re being smart at it."

Clive : "That’s the key observation right there, Sarah, I think you’re right."

Revelations : "I know we’re talking here about a story that people won’t get to read until Fear Eternal, the short story collection, is published but it’s an example for me of one of those times that an idea splits and finds its way into different narratives. In your papers from the late 1990s there’s the beginning of a story in which a young girl called Mercy has a father whose job is to maintain the lightbulbs on the top of an apartment building that are arranged into an image that’s advertising the Commexo Kid."

Clive : "Ha!"

Revelations : "Her father’s job is to make sure the bulbs are all lit all of the time so if a bulb blows, it’s his responsibility to put the right coloured bulb back into this display, and to keep the image of the Kid clean. The whole world is controlled by the Commexo Company. Mercy knows an older man, an ex-wrestler called The Jackal, who lives in an apartment just down the street and he’s the only person Mercy knows who expresses any distrust about the Commexo Kid’s operation. Then one day a big dark car draws up and someone asks Mercy to get inside... and the pages stop. Mercy and The Jackal, as now written, takes place in an entirely different world, it's taken some names and other elements from that beginning, then gone in a very different direction, and the Abarat has taken other elements and gone in another entirely different direction!"

Clive : "Yes. Of course, I have no memory of any of that! The wrestler part, that piece goes in a third direction, if you will in the current tale."

"Something you said Sarah, about Mercy and The Jackal being a fable, has been very important in the way that I have polished the narrative. ‘Joseph was a woodcutter and a kind and gentle man,’ that’s the opening of a fable, isn’t it?"

Revelations : "Perhaps another influence on it seems to be a combination of The Decameron, Canterbury Tales and Arabian Nights from Pasolini."

Clive : "I think that’s superb, I think that’s so much on the money, I hadn’t even thought about that. You know my passion for all of Pasolini but those movies particularly and they were revelations to me when I first saw them, they were."

Revelations : "The first time I saw all three of them, I couldn’t understand the narrative through-line at all because a lot of them were set pieces, beautifully filmed set pieces but ones where I had to try and work out why the character came to be in this situation and how they’d got there – and there’s a little bit of that in Mercy and The Jackal where it bounces to the next part of the narrative and you think, oh that’s kind of interesting, now they’re here..?"

Clive : "And yet everything comes around eventually, even if it seems like a pinball machine, almost arbitrary. My voice, my fabulist voice if you will, as opposed to my straightforward narrative voice of Coldheart Canyon or whatever, is the character of the narrative. It’s almost as if this is a witness’s tale, as perhaps all fables are – you’re not involving yourself in the particulars of any particular character or any particular set of characters. You’re saying this happened, and then this happened, and then that happened, and I as the narrator perhaps am a little astonished that it can be made to close in a satisfactory fashion without trying to force emotion into characters I have not written emotionally about. Does that make sense?"

Revelations : "If you did write it like that it would be judgemental. It would be your thing and you’d be saying this is what you should take from it."

Clive : "Now what’s interesting about that is that’s what fables used to be. Aesop’s for instance, are teachings, aren’t they, they’re teachings in the form of narratives. Though I’ve used the Aesopian model and taken the teaching out."

Revelations : "Yes, you don’t have the waggy finger but you still have truth is good, standing up for people is good, love is good, so you’re still saying those things. War is bad..."

Clive : "Yes, they’re not exactly profundities, you know! But yes, your point is well taken. The attitudes I’ve taken are attitudes I would take in another book but I don’t invest the characters with those feelings. At the end, I don’t believe we say goodbye to the characters in the way we say goodbye to Gentle and Pie. I am deliberately disengaged from them, the way I’m telling the story. I’m not investing my emotion. I could not have cried at the end of Mercy and The Jackal, but ‘we’ll all follow him by and by’ at the end of Imajica or ‘and this story having no beginning will have no end’ were things that, when I discovered they were waiting for me, made me sob like a baby, in part because I had started a novel with a challenge of doing something Melville did with ‘Call me Ishmael’: ‘Nothing ever begins’; three words in a sentence. I wanted something that was looking up to one of the authors I admired most in the whole world and saying, ‘can I start a novel with three words and make it work?’ and only discover 700 pages later that it was also the end. I didn’t plan the end. I didn’t start it knowing what it would give me in the end and that’s a clue I think to why I don’t remember things: these are gifts and I’ve said this to you many times, I know and you know, ‘Life is short and pleasures few...’ ‘Brother Plato...’ these are narratives that I wrote in the night and then found on tatty pieces of paper beside the sink and I think that this… OK, writing hurts me. I wouldn’t do it if it hurt me badly enough, but it throws me around in a way that we’ve never really discussed. By the time I’d finished the final draft of Mercy and The Jackal, I was wiped – I am wiped – and I was trying to work out what it is about writing that does that to me, what am I plunging my hand into – and I don’t have an answer to this so it’s not a rhetorical question – what am I plunging my hand into that, when it’s pulled out, hurts? I don’t have any answers. I only know that the fable construct allowed it not to hurt so much because I wasn’t investing in the particularities of the pain of the characters themselves. I was observing them remotely."

Revelations : "So maybe we contrast that, Clive, with how you feel about Candy? You’ve been invested in Candy’s adventures for more than twenty years and you’re still invested in finding the absolute right way to conclude her story."

Clive : "Right, and may I add, everybody’s stories – well maybe not everybody’s – but Mater Motley, obviously Carrion, Malingo, the Brothers: there’s a cast list, if you will, of maybe thirty characters that I am deeply invested in; and you might be surprised to find some of their names in the list but I know what’s going to happen to them and there’s… I don’t want to make this sound like a trick because it isn’t a trick or a conspiracy if you will – it isn’t a conspiracy – what I mean is I’ve placed certain characters within the narrative knowing that they haven’t had a lot to do – but they have a lot to do...

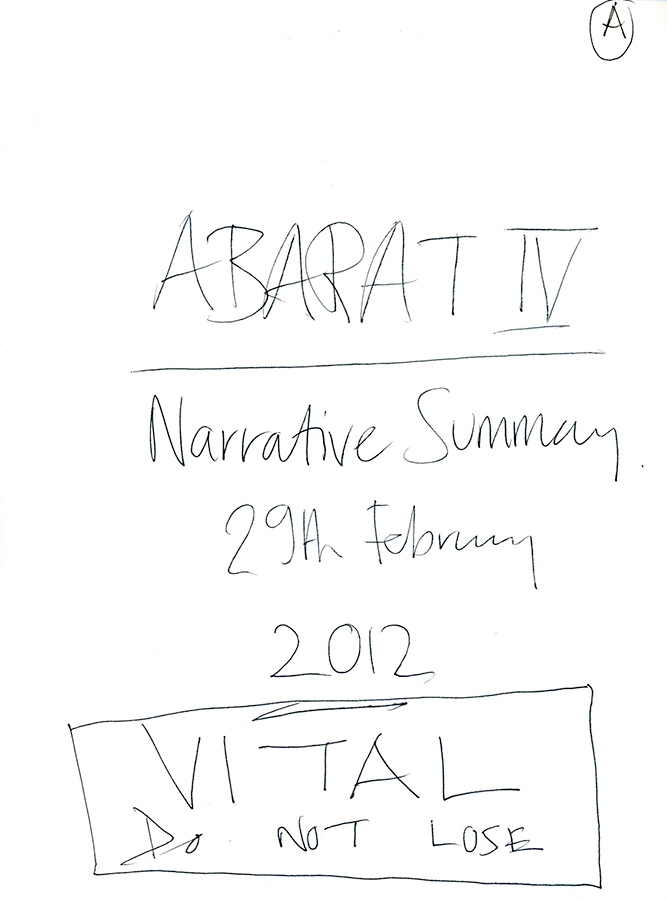

"I’ve laid those folders out, and they’re all Abarat Four and Five – that’s not all of Five, but it’s all of Four. They’re not redraftings of things: some of them are typed versions of handwritten things but not many. In other words, there’s a lot of stuff written. This was a book which became two books which became four books which became five books and I slapped myself very sternly in the wrists and said don’t you dare let it go to another one..! Because this story, having no beginning will have no end.

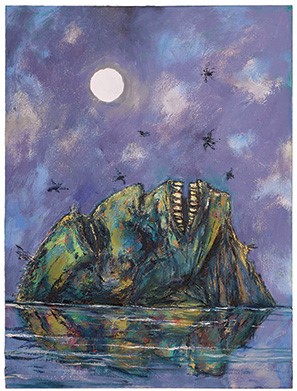

"Last night I was in what used to be my writing room and now is filled with paintings and I was looking at one-third of the triptych of the islands and I was thinking ‘what fucking mood was I in when I undertook this?’ because the much-missed Robbie built the stairs to go up to that painting, because it was so big I couldn’t reach the top of it, and with the exception of you two and maybe three or four others, I painted those paintings on my own, through the night very often as you know, naked, dancing, messing around, having a fucking glorious time, even when it was a painting I was going to throw away. For some reason that only God knows, I was gifted with the energy to do really quite a lot of work in a small time, or a smallish time. What the hell made me say ‘I’m going to make this painting 25 feet long and 12 feet tall’? Or whatever the size of the Islands painting is. You know, it was practically a marathon to get from one end of the painting to the other.

"I’ve invested more time in the Abarat than I have anything else I’ve ever undertaken and I know what’s going to happen, and I didn’t realise how carefully I had planned it in my subconscious. I’m sort of surprised where things fitted as neatly as they do, which is exactly the same thought as ‘Nothing ever begins’ at the beginning, ‘and this tale having no beginning will have no end’ at the end.

"It’s like my storytelling self shapes my more conventional, my more prosaic, self into remembering some stuff and forgetting other stuff – there’s a reason why there’s notes everywhere, there’s a reason why I write everything down, because otherwise I’ll forget it. I mean how dangerous is it to have a really fucking great idea – not to change the subject, but you have that piece of paper that says ‘Do Not Lose: The Solution to Art 3!’ or whatever – I have no idea what the solution to Part 3 is because I wrote it down to remember it! Does that make sense?"

Revelations : "It does in the context of another thing you’ve talked about – you’ve talked of the ideas vying for attention in your head: it takes something special to lodge for long enough for you to devote a significant amount of time to it, it has to really catch you; but ideas that you’ve had years before suddenly come back and find their time – and sometimes that’s because you’ve found them written down on a piece of paper and you go, ‘Ah, now I know where to put that!’"

Clive : "You are so right, so right. And it took me a while to realise that was the way my mind worked. It’s why I think I was a later writer, as a writer of prose. When you write plays, you’re in the dialogue – I would always speak it aloud so I’d have the dialogue: those plays would write themselves, that sounds very cocky, I don’t mean it to, I mean it to mean that I am sort of passive in the face of dialogue. If dialogue goes off the road, I instantly know that it’s off the road. I remember the director of Colossus saying ‘you’ve changed the last word.’ He’d seen my handwritten draft and I’d scratched something out. I’d written, ‘What kind of world is this?’ and he thought the answer I’d written was ‘Goya’s’. The answer was not ‘Goya’s’, the answer was ‘Ours’. Because, you know, I scratch things out very thoroughly. He thought he was being clever about an error but in fact no, no, no, there was only one way that could end: by the artist – me – and the artist – Goya – (God, if only!) returning the world unto the true owners of that world, just as you hope any work of art that you make will be received and taken and taken to the bosom of either an actor or a viewer.

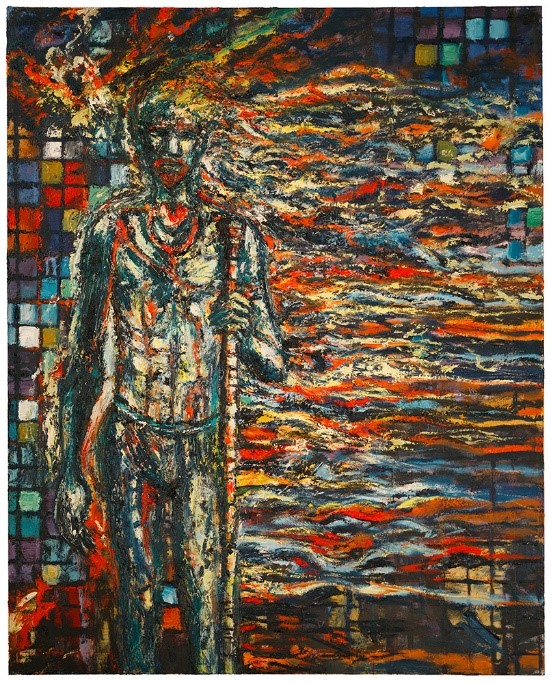

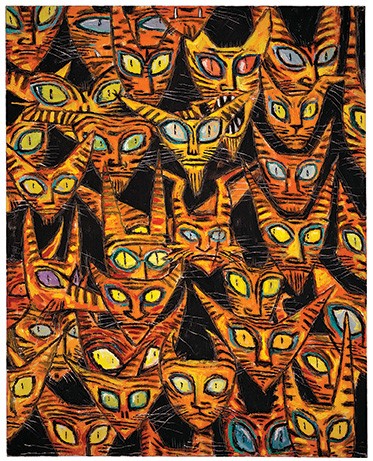

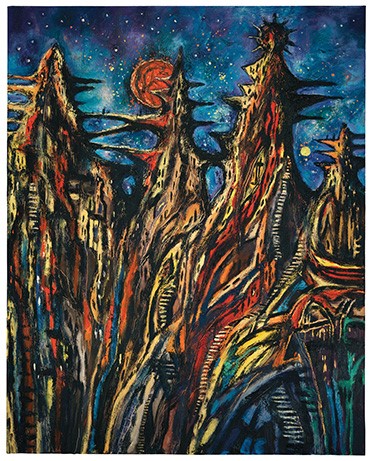

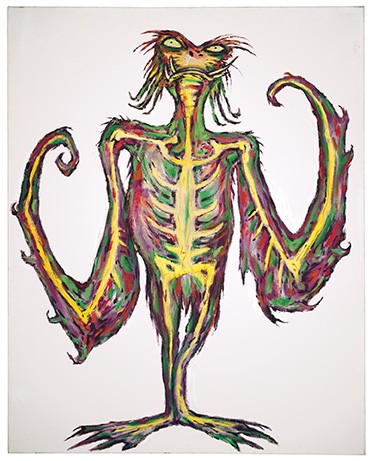

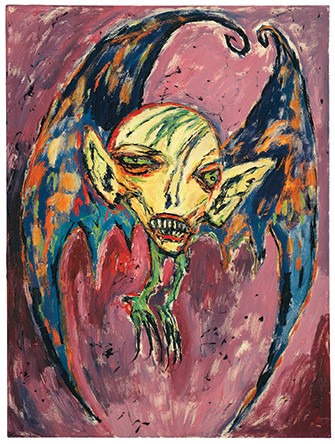

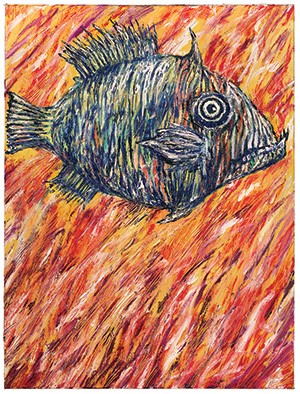

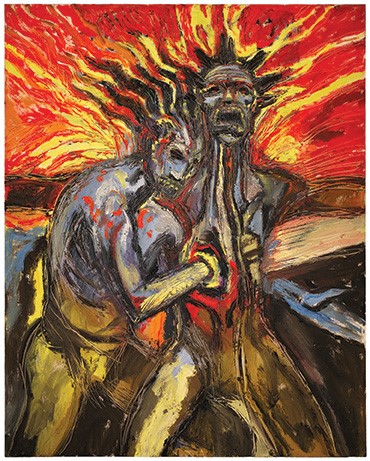

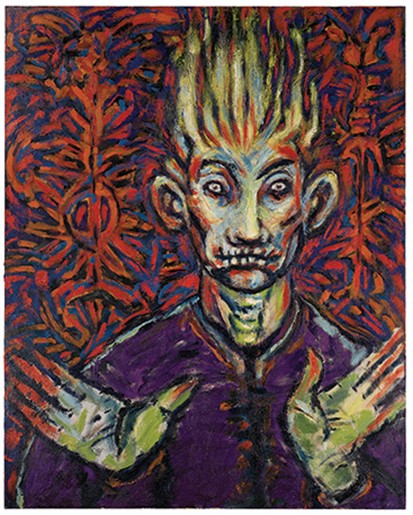

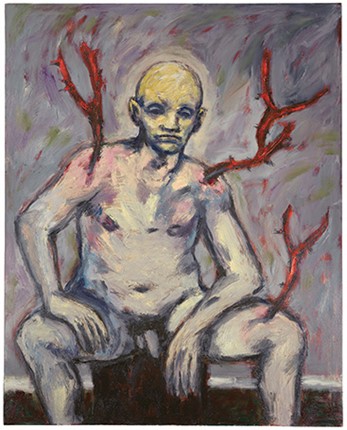

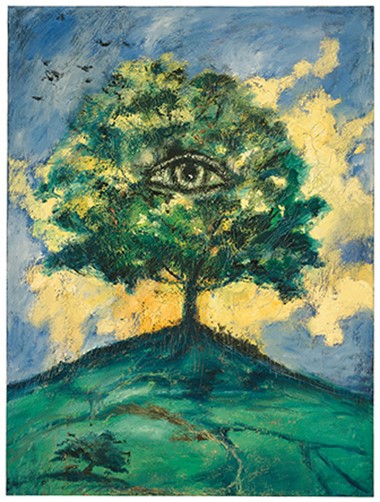

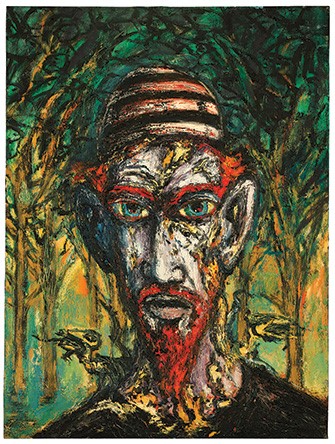

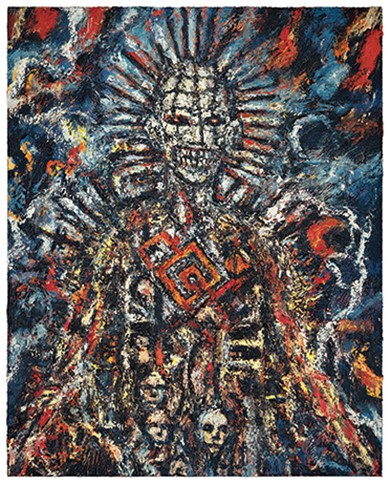

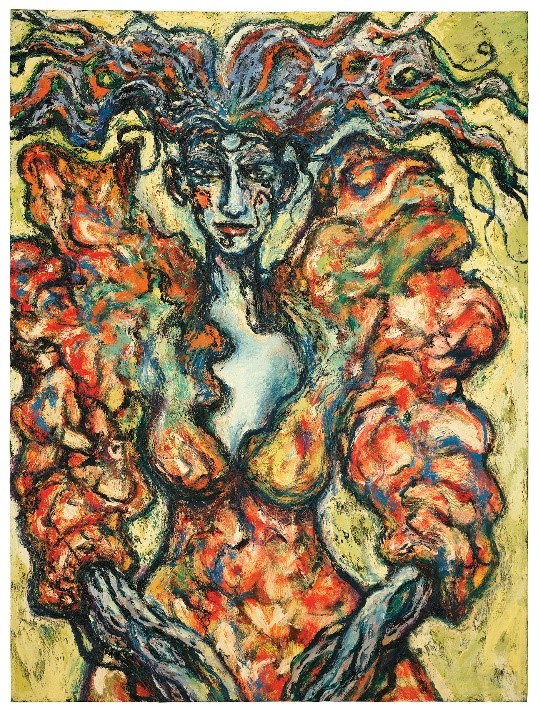

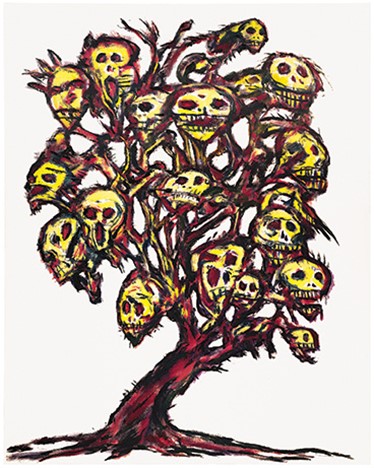

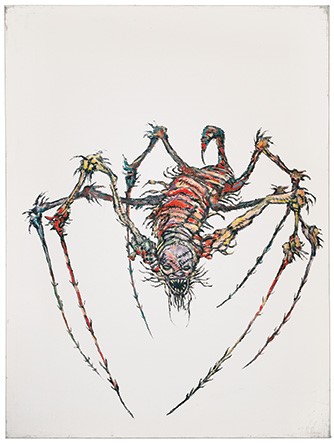

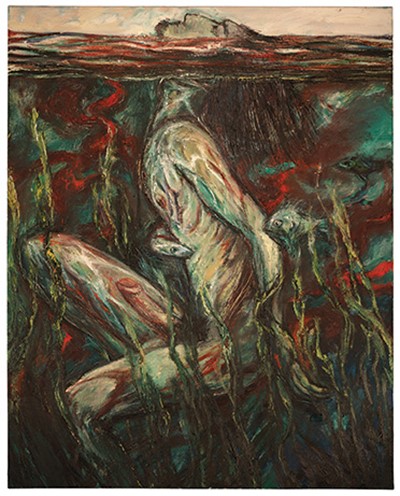

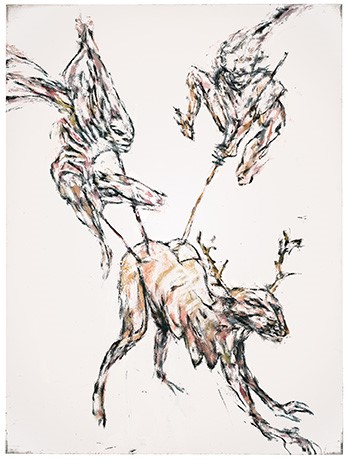

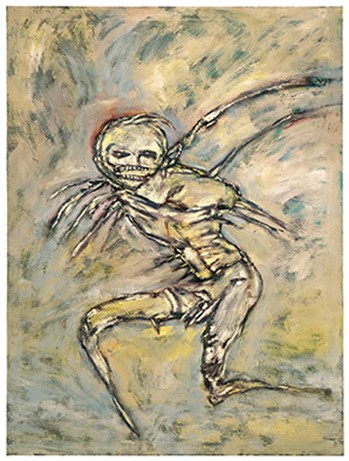

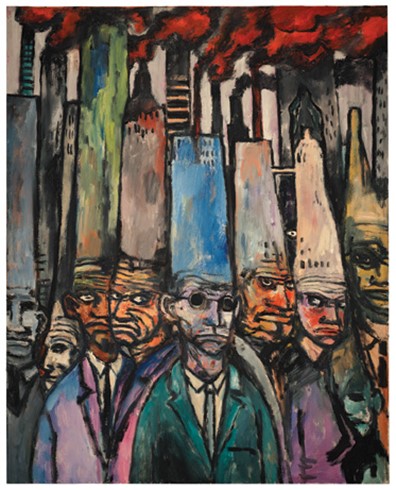

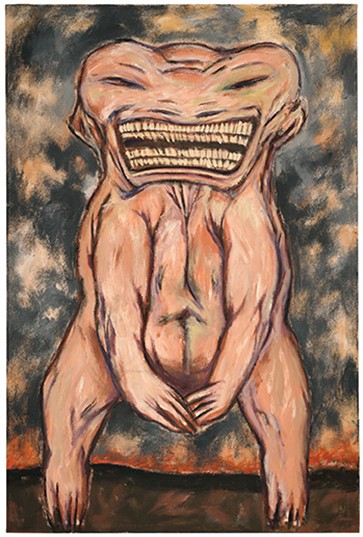

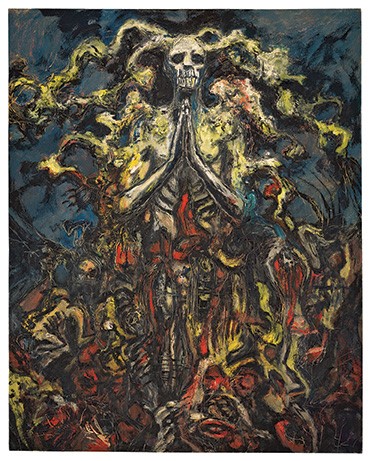

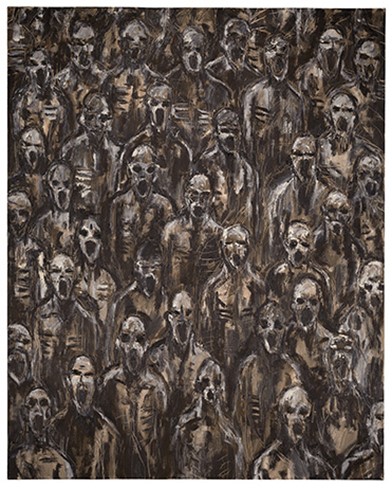

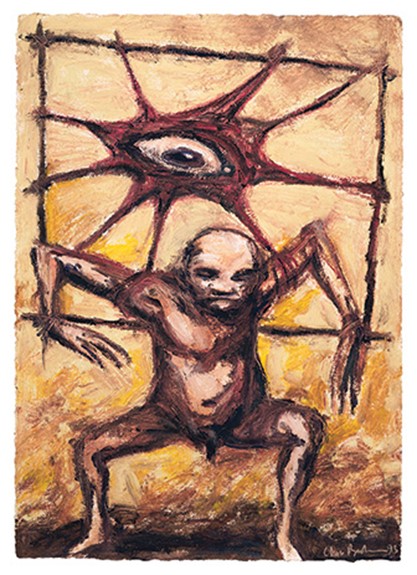

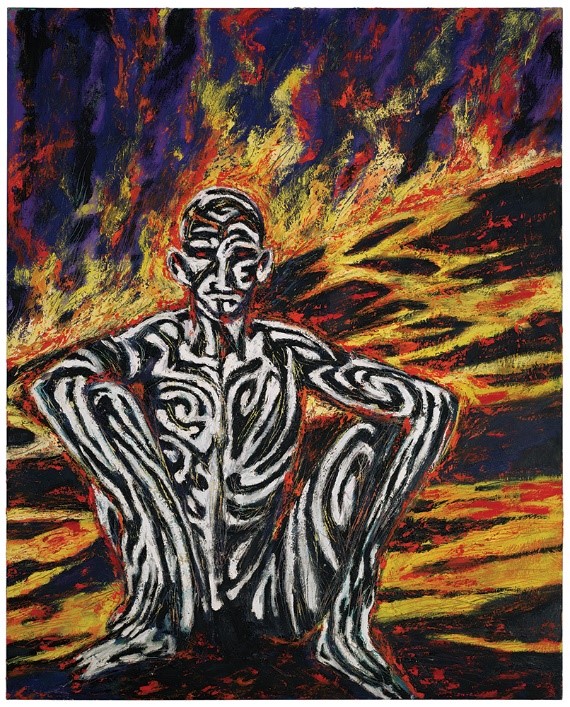

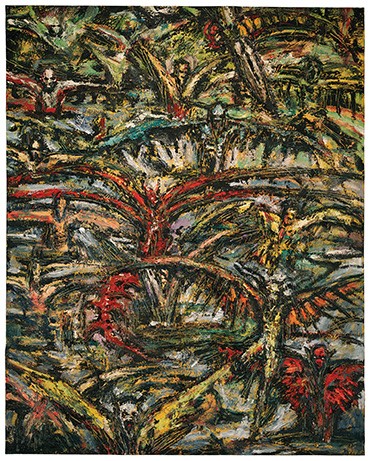

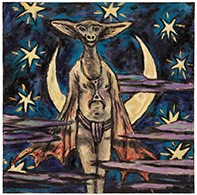

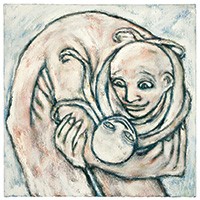

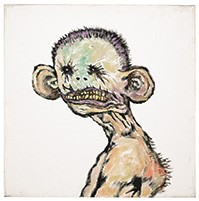

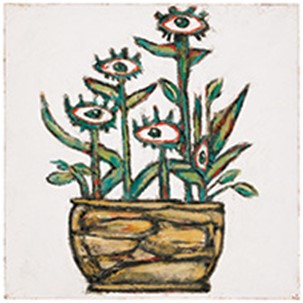

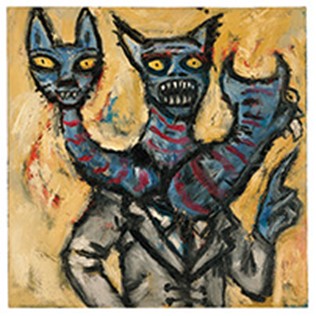

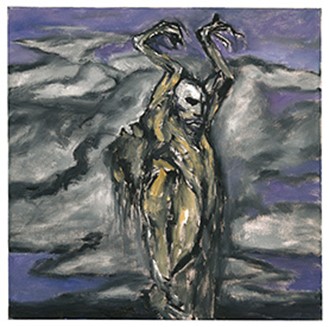

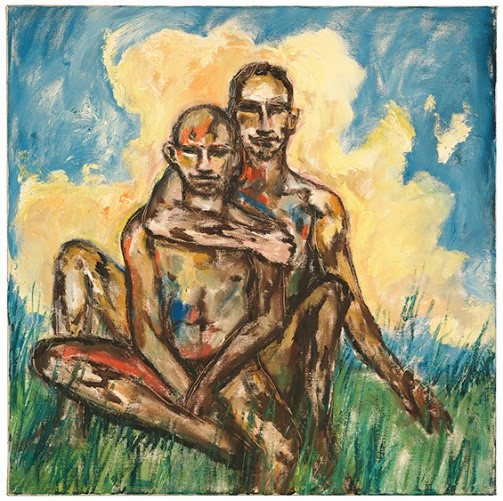

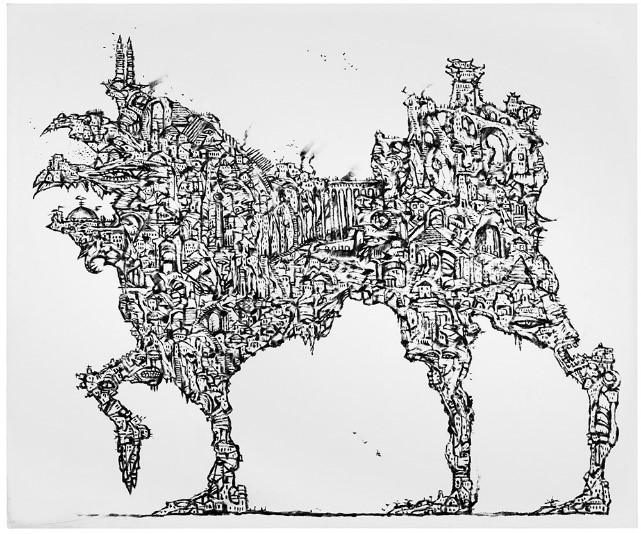

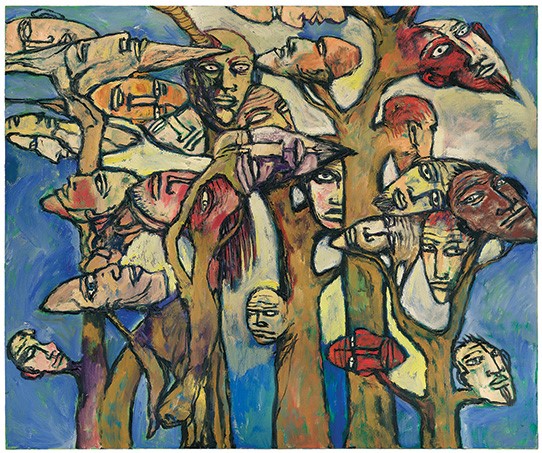

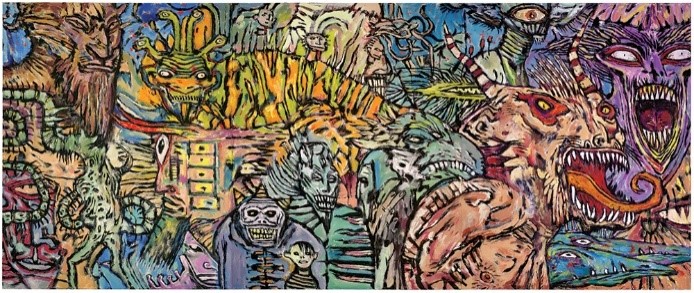

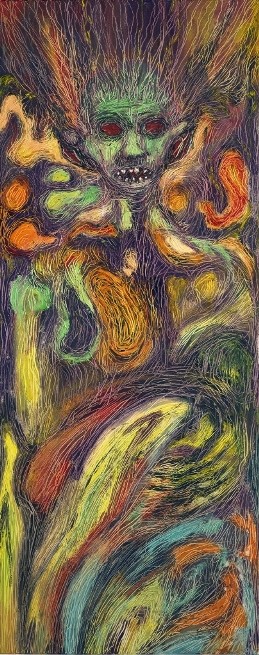

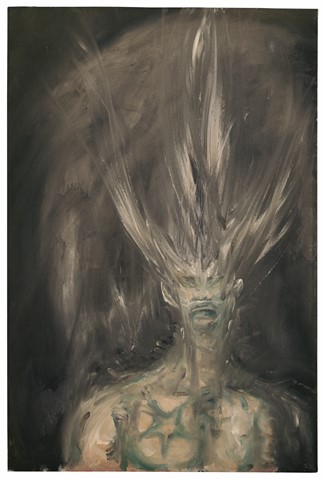

"I’ll stop soon because I’m getting weary but I want to say one more other thing about painting: it’s about discovering that, in the last seven years or so, more than forty of my oil paintings have been sold without my knowledge or instruction, together with countless numbers of my works on paper.

"These paintings, which should be here with me, are gone and my feelings of hurt, my emptiness at their absence and my rage – yes, a profound rage – have not diminished for a single moment in the time since I first learned of their removal. I know they’ll be in good homes, but in many cases, I just don’t know where. I’m sure that the people who took the paintings and sold them will say that I knew all about it, but I didn’t, I had no idea, and I’ve not been given any records at all by any of them that tell me who bought them.

"Maybe the two of you can show images of the paintings I know are gone?

"There may be others too, so can I ask anyone reading this for your help in filling the gaps in my knowledge and understanding please? If you bought one of these paintings – or any others – in the last seven or eight years, could you contact me through Phil and Sarah please to let me know that the paintings are safe and in loving hands, and will you two put the details together for me?"

Revelations : "Yes, of course we'll do that." [EDIT: Please see images at the end of this interview.]

Clive : "My thanks to everyone for your help. Thank you beyond words.

"I should also say that selecting paintings now to put up for sale going forwards is splendid because I know they’re going to find good homes too. With the paintings we just talked about, though, it’s hard because I don’t know where they’ve gone. While I want my paintings to be in other people’s hands – and it’s lovely that you’ve got paintings that I know you love, and I know with others it’s the same deal – the only time that I feel a sense of loss is when there’s an emotion tied to the painting which is in the strokes. The paintings I make are very different: some are scratched to buggery, you know, I mean I make holes in the canvas with the knives I use; some are really rather placid and simple; and I suppose that ties to the emotional state I’m in when I’m making them, yeah? But I feel sometimes that paintings haven’t yet given up their secret to me – you would think, ‘well, you put it in there...’ but I don’t really feel that at all. I feel that of all the things I do, painting is the biggest mystery. I mean, I remember you saying, Phil, to me that you didn’t like the bottom right hand corner of the painting of the guy who’s spearing the demon, the man on horseback, and I said to you, yeah, I don’t like it either and I never solved that, I never solved that.

"Practically everything you guys say to me is written on me, comments you make: you may say, ‘Oh, it’s a fable,’ Sarah, you toss that off, or Phil may say, ‘I don’t like that bottom corner,’ and you think oh, Clive won’t even remember that: I do! And I love it, I take these things to heart, you’re my dearest friends of course and I take these things to heart."

Revelations : "That’s very dangerous..!"

Clive : "What, taking these things to heart?"

Revelations : "No, taking us that seriously!"

Clive : "Well, let me say this and we’ll maybe close; it’s two things. First, if I don’t take it seriously from you then from whom? And secondly, many a wise thing is said in jest...

"This is the first time I’ve been awake enough – and I think that’s not a mistake that I’m using that word, you know, having emerged from a post-comatose state – I feel like every day I wake a little bit more and I have become passionate about using our collective voices to make sure that people do know the books are out there in a world which is increasingly alienated from the form even. You know, I think I was told that it was 3% of Americans who read novels, or perhaps 3% have books in their houses, it’s a very small number and that stuck with me for a long time. The solution to it I think is to get out there and talk about what you’re doing and I feel that this conversation is part one in a much longer conversation because there’s a lot of things to talk about – the poems, and the paintings I’m making right now and the way, you know, not being able to stand the way I used to is changing the way I paint, lots of stuff. So thank you, as ever."

Revelations : "And as ever, thank you, Clive!"

Artwork information request: