Abarat: 2B (Or Not 2A)...

The Fifth Revelatory Interview - part two

By Phil & Sarah Stokes, 22 July 2003

Revelations : "You mentioned Seraphim - it seemed like at the back end of last year you were everywhere as Abarat came out, Saint Sinner went out, there were some movie deals and the Tortured Souls signings, then it seemed like radio silence for six months - though I can now understand what you were up to!"

Clive :

"Yeah, it was completely deliberate. I was like, 'I have to get this book right,' and I said to my agent, Ben, who is marvellous, I said leave me to clear this and he was

wonderful. I just needed to get this book right. And it's also, I think, important not to become flavour of the month. I think we're sort of in a culture which makes

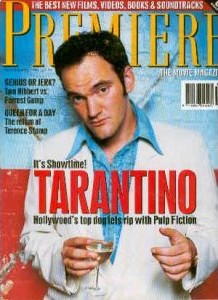

people flavour of the month and then sort of drags them down again. What the world did to Quentin Tarantino - you know? There was a time when you could not

pick up a magazine without Quentin or turn on a television show without Quentin being on there opining about something - and always wittily; he was a very good

interviewee - but suddenly there was too much of him, suddenly we didn't want to see him any more.

"And I think writers and - this is certainly true of me as a painter, I wouldn't universalise this as far as paintings are concerned - but I'm not very good at talking about

the process of how a thing appears on the canvas, because it's a mystery to me! I can talk about it in practical terms, something about technique, or whatever, but

how or where it comes from... I'm a little bit befuddled by that and so I don't have a huge amount illuminous to say. Now, that isn't to say that when this

whole Abaratian Quartet is finished and I have some distance on it I may not have some sort of revelation, but right now I'm in the midst of it and it remains

curiously mysterious.

"I wanted a poem at the beginning of the second book, which would be about dreaming and dreams such as... I like the poem at the beginning of the first book

and I'd finished, almost finished the text and nothing was coming, and I lay down to have a siesta and sat up a minute later and I have books, you know, journals everywhere and in the

time that it took to write it, that is to say a minute and a half, wrote down twelve lines - three stanzas of four lines, all of which rhymed and all of which were

perfectly argued. Now, what's bizarre about that is that there is something magical about that to me."

Revelations : "To you! I'd never get them to rhyme!"

Revelations : "Well, mine might rhyme but no-one would want to read them - they'd lose a bit of sense on the way!"

Clive : "I think the thing is there's two explanations that work for me. One is that my subconscious is busily working away all the time figuring things out - which is possible, and the other is the chanelling explanation that this stuff is simply... that I'm just the conduit for stuff which is coming from some other place - and I don't entirely discount that possibility and I don't discount the possibility that all imaginative processes... that we are conduits, it's a Blakean point of view, certainly that there's something of opening a door to something and you just have to learn to let the door open. And I think when I over-think things, as I did with this second book, this first version of the second book, I effectively closed the door and what I needed to do was leave it ajar again and I think that's why the second version, as it were, the proper version, the real version seemed to me to work so much better was that I was letting it tell itself as opposed to insisting myself upon it. And I don't, going back to this point about these pictures, I cannot tell you where any of this comes from and I can't tell you how these things come into being."

Revelations : "Is that still true for the later paintings where you are following the narrative?"

Clive :

"No. That would be an exception. But even there I'm trying wherever possible to leave open the possibility that I will doctor the narrative in some small measure,

because I have a final pass at the narrative to go to reflect the painting and that I've already done with these works on paper which are everywhere, scattered

around, pieces which are for the second book. I'm definitely going to... it's a changing of an adjective sometimes, it's red becomes yellow or whatever, simply

reflecting what my subconscious, my eye, my hand has instructed me to do in the painting itself. I'm not very good at willing things.

"I find the editorial process immensely useful because it's the first time somebody will tell me what I've done and very often there's an 'Ah-ha - yeah - that's

what I was going to!' and that will help me sometimes refine a point, to hear somebody say, 'Well, you know in chapter four you've done this and then it's

re-echoed there and...' "

Revelations : " 'Hell, yeah, I am a smart guy - look at that!' "

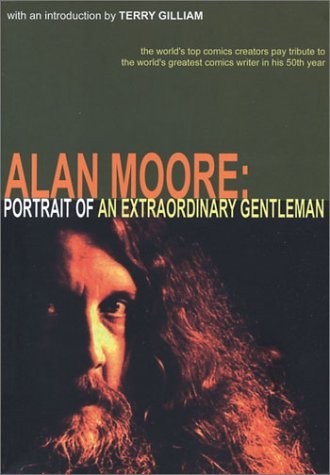

Clive : "And I think that might have something to do with fantasy itself. I mean, fantasy... Is it Ursula Le Guin who argues this? Some writing, some very smart writing about fantasy... Oh, I know who it is, it's Alan Moore - I think - Alan's fifty this year and there's a birthday book with a number of his friends writing and drawing and celebrating him and at the end there is a dialogue between him and Dave Sim who writes Cerebus and I think of Alan as being by orders of magnitude the greatest writer who ever came into comic books, and are you familiar with Promethea? Do you read Promethea?"

Revelations : "No, I'm still on 'old' Alan Moore."

Clive : "Ah - Swamp Thing and Constantine? You should have a look at Promethea - she's collected; her stories are collected in four hardcover volumes - pretty amazing! It's basically a book about magic and the history of magic, but he, Alan, and Dave Sim talk and exchange in letters or e-mails, which are given to us on several densely-typed pages, their views on a lot of things - religion and art and so on and it's so rich, this exchange, it really is an extraordinary exchange and I wholly recommend it. I was trying to figure out even as I was talking where Alan Moore writes about it, I just remembered where he writes about this - he writes about the point I'm about to make at the beginning of, in the introduction he gave to a comic book version of The House On The Borderland which you're familiar with, of course, an amazing novel. He points out that certainly until the early part of the nineteenth century, fiction was fantasy and the notion of realistic fiction is a relatively new idea; the idea that fiction is somehow bounded by the laws of 'reality' is, that terribly limiting... "

Revelations : "...it's all the fault of the French!"

Clive :

"Well - maybe!

"I think Sarah's got a point, I think the French have got to take a lot of blame, and the Russians came along and the Brits. But let's not blame the novelists - it becomes

about what the critical tradition decides to say and the critical tradition, the academic tradition, frankly, starts to excise from the history of literature things which

are fantastical. And Moore points out how totally absurd this is going to look in twenty, or thirty, or fifty years' time and perhaps already is looking. I mean

I think that thing that, was it Waterstones? did in London."

Revelations : "Waterstones did one and the BBC are doing another one now - the greatest books ever - and the list has got the critics up in arms because it's populist..."

Clive : "Well, of course, of course."

Revelations : "I was in a bookshop before we came away and the shelves are stacked full of these one hundred listed books - lots of fantastical things and also the list is full of children's books which is sending everyone back to those old favourites and, more importantly, reading them to their kids."

Clive : "It's fantastic! Now, I don't think that The Lord of the Rings is a greater book than War and Peace, let me be honest, I don't, or Madame Bovary, I don't, but I completely celebrate the idea that if the vox populi wants to say, 'This book changed my fucking life, blew my mind, made me think about the world in a different way' which it certainly did for me, and probably everyone round this table, then fuck! I don't give a shit - let's celebrate it!"

Revelations : "Jane Johnson heartily agrees, because she can market it..."

Clive : "Right, right, right... Yeah and God Bless Tolkien because she looks after the Tolkien issues - as you know - it's been quite fruitful of late."

Revelations : "Absolutely!"

Clive : "So I think the fantastic presents a problem to critics because we really don't have very good vocabulary to talk about it. We hve an impoverished vocabulary to talk about not only its structures but also what it does to us. We can talk about naturalistic fiction relatively easily because we can compare it with nature - right? 'This is Dickens talking about the social conditions in London in 1866' or whatever it was. Now, 'Is this literally what he was discussing?', 'Is this literally the way it was?' and you can't do that with a work of fantasy. You can't do that with Paradise Lost, you can't do that with A Midsummer Night's Dream. And I always remember a fellow called Nicholas [Frimpton] who is now a critic, maybe not now, but he certainly was. Nick taught me Poe without ever mentioning, without ever mentioning that Poe liked to scare people. He also taught me Whitman without ever mentioning that Whitman liked to suck cock and you know, it's that interesting selective vision and there's a reason I connect up the fantastic and the erotic because I think very often they are connected up in the sense that they are both central to our lives; our dream-lives, our erotic lives, and yet are curiously ostracised, they're not dinner-party conversation."

Revelations : "That's why you don't get out to dinner parties very often, isn't it? You're first on that blacklist!"

Clive : "It's not even that, it's just that I don't have anything to say..."

Revelations : "...that you don't 'say' in a different way."

Clive : "That I don't say in a different way? Good, that's very good, that's very, very perceptive."

Revelations :

"It doesn't mean that you don't articulate it.

"Something that always worked for me about the difference between fantasy and naturalistic fiction is a parallel with something

somebody once said that travel doesn't broaden the mind, travel actually narrows the mind. Because, once you've been to a place your experience is

locked and it's set, whereas if you read about a location you can visualise it, you can imagine it and it remains open. So it's an open vista or a panorama that

you haven't yet experienced."

Clive : "One of the reasons why I don't take photos when I travel. I hate it for that exact reason, because you lock it."

Revelations : "Because your memories are far more beautiful."

Clive : "You've got this fucking fake moment."

Revelations : "You can't lock Imajica."

Clive : "No."

Revelations : "You can know nineteenth-century Flanders, if you were there...! Or twentieth-century West London as a setting."

Clive : "Right."

Revelations : "It's an experience you can have and it's locked and it's comfortable actually. You can say, 'Ah...'"

Clive : "Right, and, 'This compares nicely with...' Where I see this most powerfully is in the mail that I get and the comments that appear either on your site or on the Amazon.com site or wherever, where it becomes very clear that there are books, two books in particular: Thief of Always for one reason and then Imajica for another reason, which are transforming books for certain numbers of people. Thief of Always because it's often the first book a kid reads and that comes up over and over and over again: 'I never liked books until I read this one,' and that's fantastic. And Imajica because, for a certain kind of reader, a certain reader, it's what Lord of the Rings was for me for a period of time - it's a book that they will re-visit and find things in and so on and I think fantasy is very hard for critics because, how do you talk about it? It sort of befuddles critics. The American edition, probably the same as the English edition, of the Gormenghast trilogy has a number of essays, critical essays, after it..."

Revelations : "Mmm - no, ours is a pretty old, well-worn paperback. Maybe we need to re-invest."

Clive : "It's the paperback, it's a big, thick paperback, maybe it's the American edition, which has some pretty good essays and one of the things is watching very sympathetic critics at work."

An unscheduled interruption by Ubu and Zoe, as Clive's two extremely friendly dogs bounded up the stairs, brought this part of the session to an abrupt ending, following which we moved to the main business of the day and the real purpose of our visit - a discussion about the plays Clive wrote prior to the Books of Blood and a look through the visual archive of those years. This latter discussion and other sessions is contributing to our series of books continuing to be researched and written - starting with this creative period - see our page of information about Memory, Prophecy and Fantasy for more details...

More from Clive on Abarat (Book One)More from Clive on upcoming Abarat projects