Nightbreed - Production Memories

The creation of Nightbreed, Clive's second directorial effort in feature films, suffered a troubled principal photography shoot, a traumatic post-production editing process and a misguided US release marketing strategy. In a great many respects, the visions captured on screen were compromised versions of the screenplay and the original intentions.We've analysed the various changes to the opening sequence and to the closing sequence and also charted two deleted scenes on other pages but here we're delighted to be able to present the memories of Rory Fellowes, Animation Designer on the movie and his fascinating first-hand observations of the stresses and disappointments associated with reaching beyond technical limitations to attempt the truly revolutionary.

With our heartfelt thanks, Rory Fellowes...

The Making of Nightbreed

An Entirely Personal Memoir

By Rory Fellowes

One way or another, everyone involved in the planning and execution of Nightbreed got into some sort of difficulty in the course of making it. Some of the time we made the trouble for ourselves, some of the time we made it for our colleagues, but ultimately no-one deserves any blame, no-one did less than their best. The trouble stemmed from one fundamental problem: Clive Barker was at least 15 and probably 20 years ahead of his time, and he was intelligent, self-aware and arrogant enough to know it.

It is no surprise then, that there is a revived interest in the project now. I am intrigued to read how well and how strongly Clive defends the finished film, though I appreciate he is a marketing artist par excellence. He is obviously pleased with it even as he acknowledges its shortcomings; the destructive interference of the producers; and the worthless marketing it got from Fox (that story as he tells it is so ridiculous it is hilarious). I should explain at the outset that my own memories of the production are largely painful but I count it among my most formative experiences in film and I do not regret a minute of my involvement in it.

I watched Nightbreed again recently, in preparation for writing this memoir, and it is better than I recalled, but it is still not as good as it should have been and could be if we were starting it today. The audience is far more sophisticated now and Clive would be given proper and informed support in remaining true to his vision. Modern producers would know what he was getting at, which they so blatantly did not then; and of course, technical advances have made easy what then were all but impossible concepts.

I watched Nightbreed again recently, in preparation for writing this memoir, and it is better than I recalled, but it is still not as good as it should have been and could be if we were starting it today. The audience is far more sophisticated now and Clive would be given proper and informed support in remaining true to his vision. Modern producers would know what he was getting at, which they so blatantly did not then; and of course, technical advances have made easy what then were all but impossible concepts.

In every department Clive was pushing the production team to the limit of the budget we had to hand and the available technology at the time, and it seemed that the producers at Morgan Creek had only a vague grasp of what was required to create anything like his vision. The largest part of the burden of that dilemma fell to Bob Keen's company Image Animation, from which that great bear of a man drove the entire Art department, all working to create the look of Midian: the main crew involved in the production of the creature make-ups and animatronics; the creature costume department; and the animation department. Everyone involved will recognise what I am speaking of, knowing what we know of the wealth of principal- and post-production techniques that we could bring to it now, and as the years roll on so it has become more and more feasible to make the film we all thought we were going to make when the project began These days any film-maker would have a pretty good idea of how to achieve that Midian vision. It would be a wonderful if unlikely event if Clive wanted to go back to the project and realise the dream he had. Back in 1989 it seemed sometimes that he simply believed he could bludgeon the production teams into fulfilling his vision but it just couldn't happen, not then. Instead he was rewriting the movie on the hoof, new pages came through every day and the pick-up shoot six months later was more of an extended principal shoot. Most catastrophically of all, Clive was forced to re-envisage the essential mis-en-scène of Midian so that it ended up an unsatisfactory assembly of conflicting concepts and styles.

There is a note in my shoot diary that reads: "(DB [David Barron] says this is a movie about 'unfortunate humans'!! Are we still making Nightbreed?)". I mention this as proof that we knew then what was happening: what I am writing here is not mere hindsight.

My first glimpse of what I took to be Clive's vision of Midian was in a short story of his called The Skins of the Fathers in one of The Books Of Blood. The story centred on a group of monstrous characters who lived together hidden underground somewhere out in the desert. In my memory of it now its central image was of a column of monsters crossing the moonlit desert, some tall and willowy, others squat and crippled, and all kinds of grotesque in between. They are retreating to their hideaway and in that moment you the reader are entirely sympathetic to them and you recognise the beauty they see in each other. You wish them well, you wish them safe. It was beautifully and so much more sparingly and elegantly told in the story than it ever was in the movie, where at its most blatant, the effort to get the audience's sympathy on the side of the creatures is positively mawkish (though it should be said, much more effective than similar scenes in the vastly more generously budgeted Total Recall). The story spoke to me of all those broken and alienated groups in society that have run off to communes in the deserts and mountains of the world, of all social alienation in fact, of racism and intolerance and that furious, shoot-first fear of strangers that seems to lie so deeply in the American psyche. For me that was the Midian we spoke of in those early months, a refuge for peaceful creatures from a cruel, witless Society.

But then that whole psycho-killer sub-plot came on board, and with it the as-appalling-at-acting-as-he-is-great-at-directing David Cronenberg. The rumour around at the time was that there was some sort of producers' expectation of blood to satisfy and this was Clive's answer. It is interesting that in talking about his relationship with David Cronenberg in later interviews, Clive speaks only of the fellow director; nothing about the actor.

So finally I come to the story of the Nightbreed Production as told by the animator and Animation Designer, as the film so graciously credited me. It was a wonderful vision and we had a great time in pre-production, but it all very nearly came to pieces during the Principal Shoot and only Clive's genius, David Barron's scheduling skills, and the crew's energy saved it.

The day I arrived in the enormous studio space that Image Animation occupied in the grounds of Pinewood Studios the  Animation Department were preparing to design an open-ended number of creature concepts for which I was to storyboard possible scenarios that we would offer to Clive. It was the idea at the start that animation would provide a lot of the interior shots of the Midian labyrinth, the crowd scenes as well as the specific creature sequences, to create the illusion of an underground labyrinth filled with monstrous beasts and their mutant human co-habitants. We were going to create all sorts of monstrous creatures to be shot on miniature sets that Julian Parry's Art department would build. I suppose one could say it was my fault that I didn't just say right at the start that we couldn't possibly do that without a much larger team of animators, but I was wildly over confident of what I could do.

Animation Department were preparing to design an open-ended number of creature concepts for which I was to storyboard possible scenarios that we would offer to Clive. It was the idea at the start that animation would provide a lot of the interior shots of the Midian labyrinth, the crowd scenes as well as the specific creature sequences, to create the illusion of an underground labyrinth filled with monstrous beasts and their mutant human co-habitants. We were going to create all sorts of monstrous creatures to be shot on miniature sets that Julian Parry's Art department would build. I suppose one could say it was my fault that I didn't just say right at the start that we couldn't possibly do that without a much larger team of animators, but I was wildly over confident of what I could do.

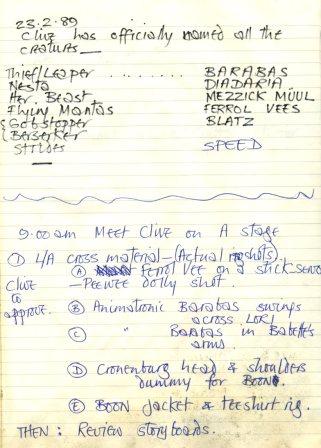

After about three months in pre-production, the Animation Department had come up with around 35 viable creature designs that Clive had approved. I had begun storyboarding animated sequences for the first dozen or so and work had begun on the first maquettes of the creatures when all work came to a sudden halt.

A huge reappraisal had taken place. The numbers didn't work. David Barron was brought on board and Gabrielle Martinelli came over from America to oversee the production. I'm not sure what purpose Gabriella served except to be the face of Morgan Creek in Pinewood, but I have no doubt that David saved the production, with a ruthless axe we all felt. The Image Animation crew was halved. Chris Figg took on a greyish hue. Clive was going rogue on him and he was getting most of the blame from Morgan Creek. One day during those weeks when the production was desperately trying to make ends meet, I was involved in a small Live Action unit shoot for the Manta sequence. There was myself, Peter Atkins, a Steadycam cameraman, and a modeller from the Art Department who was going to act as the assassin of Lylesberg. When we arrived at A Stage there were seven separate units assembling there, and three of them were shooting for  sound, with the consequence that throughout the day we would be yelled to silence by one or another First A.D. On reflection, our failings that day, of which more below, were comparatively small when set against the obstacles to efficient work we faced. I saw Chris that morning. He was his usual gentle self, urging us to believe we could do it and simultaneously obviously doubting that we could.

sound, with the consequence that throughout the day we would be yelled to silence by one or another First A.D. On reflection, our failings that day, of which more below, were comparatively small when set against the obstacles to efficient work we faced. I saw Chris that morning. He was his usual gentle self, urging us to believe we could do it and simultaneously obviously doubting that we could.

For Image Animation that terrible week started with a full crew and administrative staff numbering maybe 120 or more in total. By the end of the week that number had been more than halved. The animation team was reduced to two modellers, plus Karl and myself, and I had a list of twelve shots that had been agreed could go forward to development. By the time we began to make the animation models the list had been cut to six sequences. We eventually shot tests for five sequences plus a test for an animated make-up concept to be tried on Peloquin and Boone. We went to Final Shoot on three sequences and just two of those made it into the movie.

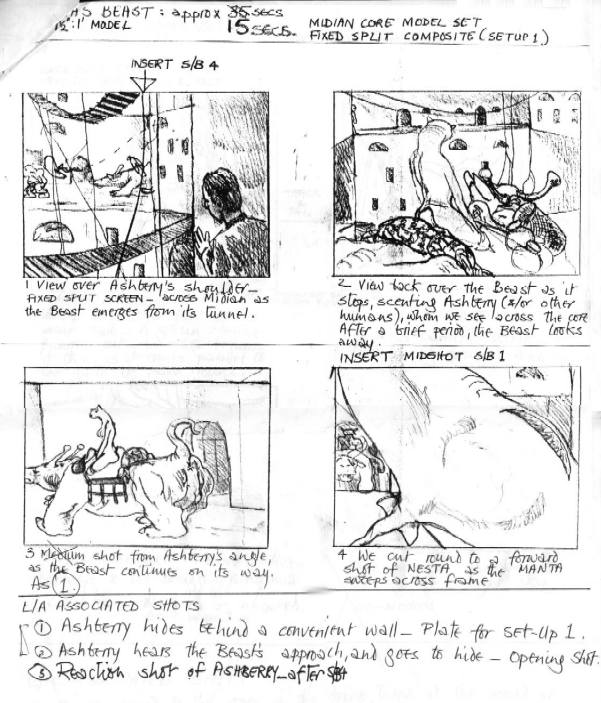

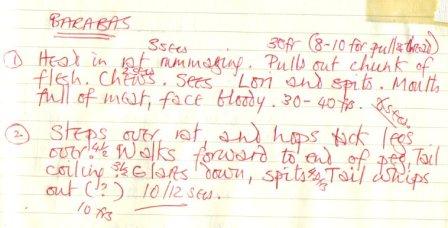

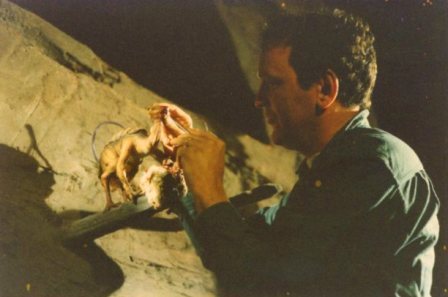

The sequences I was most sorry to lose were the transformations of Peloquin and Boone and the sequence involving Diadaria on the Mezzick-Muul (known as Nesta's Beast during production). The shot I was happiest with in the final movie was the Barabus creature, known during production at first, as the Thief, and later during the shoot, as Barabas. The other creature that made the final cut was the flying mouth that avenges the death of Lylesberg. We called it Manta as a manta ray was the basis of the design, which I started but the modeller finished, and that remained its official name. The sequence that went to full dress test but didn't go to final featured a creature called Gobstopper, designed and modelled by Howard Swindell who also made Barabus. It was some sort of compensation for me after the whole sorry saga was over that the two shots that made it to the final cut both started life with my concept drawings.

At the end of the shoot David Barron called me to his office. By then I was exhausted and had had such a bad time with the management at Image Animation I had given up all hope of defending my position. David asked me what would have happened if they had wanted all six sequences since I had used up all of the schedule to finish three. I didn't answer, or rather, I mumbled in a surly growl, "I'd have asked for more time." As it happens, I still have my production diary. I checked it recently while preparing to write this, and I discovered that out of the 37 days allocated to the final animation shoot, we spent exactly 16½ days actually shooting, while the rest of the time was spent sitting around the Westbury stage waiting for Clive to view and approve or re-direct the rushes. But by then I had lost him and any sense of support from him or from Image Animation. My wonderful cameraman and general all-round right-hand man and ever since then confidant, mentor and life long friend Karl Watkins told me to keep my head down, stop annoying people, and live with the situation. Sound advice I didn't entirely follow. The delays and misunderstandings are all too complex to reconstruct here and anyway what is the point? I wasn't the only one suffering from the shoot. There were people on the crew ready to walk some days. On F Stage during the shoot of the final battle there was so much smoke the crew were staggering outside just to catch their breath. I remember passing by one afternoon and seeing a small crowd gathered by the low wall alongside the stage. The cameraman was there and he was furious, ready to slaughter or anyway sue any producer or director who wandered by. I don't know how the actors stood for it.

At the end of the shoot David Barron called me to his office. By then I was exhausted and had had such a bad time with the management at Image Animation I had given up all hope of defending my position. David asked me what would have happened if they had wanted all six sequences since I had used up all of the schedule to finish three. I didn't answer, or rather, I mumbled in a surly growl, "I'd have asked for more time." As it happens, I still have my production diary. I checked it recently while preparing to write this, and I discovered that out of the 37 days allocated to the final animation shoot, we spent exactly 16½ days actually shooting, while the rest of the time was spent sitting around the Westbury stage waiting for Clive to view and approve or re-direct the rushes. But by then I had lost him and any sense of support from him or from Image Animation. My wonderful cameraman and general all-round right-hand man and ever since then confidant, mentor and life long friend Karl Watkins told me to keep my head down, stop annoying people, and live with the situation. Sound advice I didn't entirely follow. The delays and misunderstandings are all too complex to reconstruct here and anyway what is the point? I wasn't the only one suffering from the shoot. There were people on the crew ready to walk some days. On F Stage during the shoot of the final battle there was so much smoke the crew were staggering outside just to catch their breath. I remember passing by one afternoon and seeing a small crowd gathered by the low wall alongside the stage. The cameraman was there and he was furious, ready to slaughter or anyway sue any producer or director who wandered by. I don't know how the actors stood for it.

There were four or five months of sculpting, moulding and making the armatured foam latex models before I shot the first tests, and two months more after that before we began the Principal Shoot. Everyone at Image Animation was working all the hours God sends six and, during the actual shoot, seven days a week. And I do mean all the hours: a basic 18 hour day often ran on to anything up to a snatched nap in the studio before starting the next day's work. The animation was turning into a gruelling slog as we tried to achieve a perfection of movement that only CG has managed since. I have a note in my Nightbreed archive in which I have written down a calculation of the time required for two minutes of finished film. I must have written it before actual shooting of the animation began. It takes as its basis a production rate of 5 frames an hour or 50 frames per day. My actual average across all the final production shots we completed was closer to 30 frames per day, And on the Barabus shot I was getting about 12 frames per day, or a little less than one frame per hour (we were working around 10 to 14 hours a day when we were shooting).

When I showed Clive the Gobstopper tests he said to me, "It looks like animation." Well, yes it did. It was animation and I didn't know how to change that. Besides, this was the first test and I could maybe have improved it but wasn't about to give it a second chance and that first viewing killed the sequence.

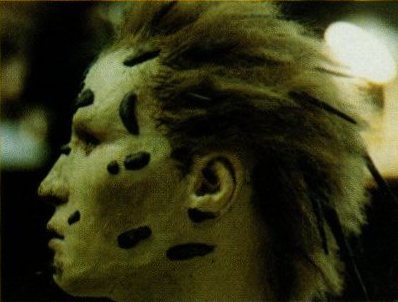

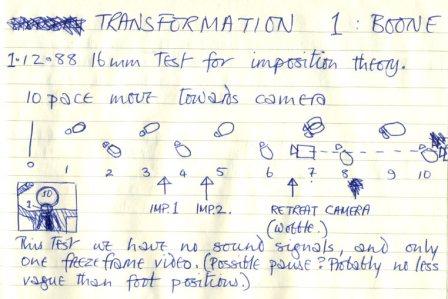

Things went much the same when I showed the first tests of the make-up change we planned for Peloquin and Boone. This was an idea I'd had to show the transformation from human to creature in Boone's case, and from nice monster to vicious monster for Peloquin. We would use a technique known as pixilation, which simply means the stopmotion animation of humans. I had done quite a lot of pixilation work, mostly for music videos, but also a couple of commercials, and I had some handy computer software that Bob had first given to me when we were shooting Hellbound. It allowed me to view two frames, the last one and the current one, simultaneously, and so make very fine movements possible to judge, as well as exact matches of position if required. On Nightbreed I had rigged up two video cameras shooting the animation at right angles to each other (this idea has since been extensively developed by the stopmotion industry and these days most if not all stopmotion animators use video reference to check their animation).

For the Boone test we planned a shot where we would see him straightening up into shot and as he did so the creature make-up would appear on his face. We pixilated him starting to stand, then we took him away for the make-up to be applied. We brought him back to the stage, fired off a couple of frames and then took him back to make-up for the next application. This was the intended process and we tested it over a small number of make-up applications. I have to say Craig was amazing, his body memory was perfect, and with almost no assistance from the video reference he returned exactly to the position he had been in for the last frame, which would have been taken anything up to an hour earlier. Nowadays such a sequence would be simple and not particularly remarkable, using CG, but back then I still think it would have been an exciting and unusual shot. In the final shot I expected the whole transformation to take place over a 35 frames or more, but for the test we only had Craig for a couple of hours so all we could get done was maybe 12 frames with a top and tail. We completed a second test with Peloquin, with him turning towards camera and his tentacles lengthening, his jaw widening and his teeth growing. The tests were short and crude, but I thought we had proved the technique and went to the rushes fairly confident. Gabriella took one look at the tests, said the transformations had gone by too quickly and she didn't think they worked. I just sat in my chair in the viewing theatre and said nothing. Clive didn't say anything and neither did Bob. We all knew she was looking for cuts by then, I was certainly already feeling bruised by the production and I expect the others felt much the same. So that was the end of that.

We also shot a test for a crowd scene involving several creatures in a model of Midian, but as David Barron said to me, explaining the decision to drop the sequence, it looked like Fraggle Rock (a children's TV series at the time), and I had to agree. That was when they started designing make-ups to create the crowds they needed. It works and the film is known for its make-ups, but bit by bit the whole Monstrous Huge Beasts aspect of the creatures of Midian disappeared from the film. Barabus made it past Clive because the animation is smooth enough to look like live action and the Manta was a plot device so he couldn't avoid using it. A week before the Final Shoot Clive changed the story for the Barabus shot entirely (he also contemplated changing the size of Barabus, but as this would involve rebuilding either the model or the set he let that one go). The creature was planned to be cute, and catch Lori's attention, make her smile (in my original storyboard he was going to steal her earring or brooch, hence his pre-production name of Thief), but then Clive decided the little creature should be vicious so Bob dug up a model of a rat he had somewhere and we did the Eating the bleeding corpse shot instead that appears in the final movie. I like the blood effect we achieved: it was done with some liquid make-up Geoff Portass gave me. To smooth the animation of Barabus we triple exposed every frame, with a separate animation pose for each exposure, a technique Karl and I had developed for Hellbound: Hellraiser 2 to smooth out those little bumps that are intrinsic to stopmotion. It took its time, as I mentioned earlier, but so what? It remains my favourite shot of all my stopmotion creature work. And I never forget that what I consider to be the best professional compliment I have ever been paid was for my work on Nightbreed. A journalist friend who was at the press showing met me in a Soho bar afterwards and, full of sympathy, told me that there were no animation shots in the film.

We also shot a test for a crowd scene involving several creatures in a model of Midian, but as David Barron said to me, explaining the decision to drop the sequence, it looked like Fraggle Rock (a children's TV series at the time), and I had to agree. That was when they started designing make-ups to create the crowds they needed. It works and the film is known for its make-ups, but bit by bit the whole Monstrous Huge Beasts aspect of the creatures of Midian disappeared from the film. Barabus made it past Clive because the animation is smooth enough to look like live action and the Manta was a plot device so he couldn't avoid using it. A week before the Final Shoot Clive changed the story for the Barabus shot entirely (he also contemplated changing the size of Barabus, but as this would involve rebuilding either the model or the set he let that one go). The creature was planned to be cute, and catch Lori's attention, make her smile (in my original storyboard he was going to steal her earring or brooch, hence his pre-production name of Thief), but then Clive decided the little creature should be vicious so Bob dug up a model of a rat he had somewhere and we did the Eating the bleeding corpse shot instead that appears in the final movie. I like the blood effect we achieved: it was done with some liquid make-up Geoff Portass gave me. To smooth the animation of Barabus we triple exposed every frame, with a separate animation pose for each exposure, a technique Karl and I had developed for Hellbound: Hellraiser 2 to smooth out those little bumps that are intrinsic to stopmotion. It took its time, as I mentioned earlier, but so what? It remains my favourite shot of all my stopmotion creature work. And I never forget that what I consider to be the best professional compliment I have ever been paid was for my work on Nightbreed. A journalist friend who was at the press showing met me in a Soho bar afterwards and, full of sympathy, told me that there were no animation shots in the film.

One event has haunted me ever since, not least because I have long ago worked out how to do what I failed to do then. For years I would beat myself up for the umpteenth time for not thinking of this or that alternative way to get the shot when I needed to. We had to shoot the live action sections of the Manta sequence. It was that fateful day on A Stage with the 7 units shooting simultaneously. Peter Atkins was to direct but as we headed for the set he said I should do it, it was my sequence after all, and like a fool I fell for it. I don't know of course, but I have always suspected that Peter knew all too well that we were inadequately prepared and he wasn't about to take the blame. That was for me to do and I did... We had a nice young American lad, Tom, one of the modellers from Image Animation, playing the role of the shooter who is to have his face ripped off. He was just an artist, not a stuntman, and try as I might I couldn't figure out how to shoot him falling on the ground if he wasn't prepared to actually to fall flat on his face and maybe smash a couple of teeth for art, something he adamantly refused to even try to do. Since then, of course, I have dreamed up a number of alternative techniques, but that day I simply abandoned the hope and we got what we could. The steadycam guy was brilliant, brisk and efficient. I think he saw my plight and sympathised and did his best in the circumstances, but he couldn't think of a way round Tom's refusal either. At rushes the next day Clive asked if I had got a shot of him hitting the ground and I just said No. I didn't explain, it didn't even occur to me to try to explain. What would I say? "But sir, he said he wouldn't do it, sir..." It meant I was off Clive's list of potential second unit directors, that was certain. By then I'd had my troubles well brewed at Image and I was just praying for it all to end. I remember sinking down in my seat and praying for the earth to swallow me and wash me down with a barrel of whisky so I could forget...

One event has haunted me ever since, not least because I have long ago worked out how to do what I failed to do then. For years I would beat myself up for the umpteenth time for not thinking of this or that alternative way to get the shot when I needed to. We had to shoot the live action sections of the Manta sequence. It was that fateful day on A Stage with the 7 units shooting simultaneously. Peter Atkins was to direct but as we headed for the set he said I should do it, it was my sequence after all, and like a fool I fell for it. I don't know of course, but I have always suspected that Peter knew all too well that we were inadequately prepared and he wasn't about to take the blame. That was for me to do and I did... We had a nice young American lad, Tom, one of the modellers from Image Animation, playing the role of the shooter who is to have his face ripped off. He was just an artist, not a stuntman, and try as I might I couldn't figure out how to shoot him falling on the ground if he wasn't prepared to actually to fall flat on his face and maybe smash a couple of teeth for art, something he adamantly refused to even try to do. Since then, of course, I have dreamed up a number of alternative techniques, but that day I simply abandoned the hope and we got what we could. The steadycam guy was brilliant, brisk and efficient. I think he saw my plight and sympathised and did his best in the circumstances, but he couldn't think of a way round Tom's refusal either. At rushes the next day Clive asked if I had got a shot of him hitting the ground and I just said No. I didn't explain, it didn't even occur to me to try to explain. What would I say? "But sir, he said he wouldn't do it, sir..." It meant I was off Clive's list of potential second unit directors, that was certain. By then I'd had my troubles well brewed at Image and I was just praying for it all to end. I remember sinking down in my seat and praying for the earth to swallow me and wash me down with a barrel of whisky so I could forget...

So that is it. It was a hard time but it was one of the most important times in my career and I will always thank Clive and especially Bob for that. There are some things that I have come to realise in writing this. First and foremost, alongside "Free Jimmy", a Norwegian CG animated feature film I worked on a couple of years ago, Nightbreed and Hellbound are two of my most enduring professional memories. I have made other films, along with TV series, commercials, promos, all the stuff of the industry, but those three stand out and I realise that though my memories of Nightbreed are fairly fraught I wouldn't give up one second of it. I learnt as much by it as I paid for it in pain and strain. My Features stopmotion career was ended by it, but the end was nigh for stopmotion in Features anyway. And I do have those great memories: Hellbound was a triumph and Nightbreed was a triumph of survival, but both were vivid, exciting, professionally engaging, and most of all, as proven here, unforgettable experiences. I made, as I have mentioned, one of my top three favourite shots for Nightbreed, and professionally, I think I got just about as far as I could in the refining of stopmotion to suit the needs of late 80s directors. CG was coming and I went to meet it.

The fact is we were too late for stopmotion and too early for CG. We were trying, with our triple exposures and video cross-referencing, all our clever schemes and techniques, to get around the limitations of stopmotion. This wasn't like the days of Ray Harryhausen, when the stopmotion was part of the charm and appeal of the movie and usually a central feature of the production. We had a few seconds on screen, it was meant to be invisible, and Gods bless us, we more or less managed that in the two shots that Clive used (and we got pretty close as I recall, in the Mezzick-Muul shots, if that sequence is ever released). But it probably came at too much of a cost: too much for the production (I dread to think what the money to seconds ratio was like); for my self-esteem (though I got that back quickly enough. You don't survive in film if your self-esteem is not robust); and for the job satisfaction of my crew, though I am sure none of them regrets the experience. Karl Watkins, being the energetic, talented and clever man he is, took the opportunity the film gave him and turned it into a highly successful career as a Director of Photography. Howard Swindell, that brilliant sculptor of Gobstopper and Barabus, has gone on to carve out a career in CG too: we worked together again in 2004, in Pinewood, on The New Captain Scarlet TV series; but the other modeller who stayed on the team to the end gave up film not long after Nightbreed. Bob Keen is still out there, staunchly sticking to practical prosthetics, but Geoff Portass has more or less left the industry. Chris Figg, David Barron and Julian Parry and lots of the others are still working in the wonderful world of moving images. And all that is, of course, not to mention last but utterly not least, Clive Barker, still creeping out the world.

©Rory Fellowes - February 2009

Rory's website

Anatomy of two of Nightbreed's deleted scenes - including one of the animated sequences that Rory mentions above