Interviews 1995 (Part Two)

Love, Death And The Whole Damned Thing

By Charles N. Brown,

Locus, Vol 34 No 4, Issue 411, April 1995

"One of the things that worries me constantly about generic writing, and generic painting as well, is how we refuse the word 'art'. We're embarrassed by the word 'art' because it brings with it certain responsibilities. We're uncomfortable with the notion of being called artists, because it feels as though we'd better defend ourselves. It's particularly true of genre filmmaking. John Carpenter once told me off very sharply on television for referring to myself as an artist. You don't have to be Tolstoy to call yourself an artist - you can be writing minor fiction. But I think writers should stand up and say it, particularly in the genres in which we are all engaged, because for too long we've been passive and allowed editors and publishers to take the art away and debase us, frankly, by never allowing the subtextural life of the work to mean anything, to sell the sizzle, the sex, the trivialities. Why shouldn't a fictional form that can deal with the problems of physical frailty, our aspirations of divinity, and the creation of worlds, the destruction of worlds, the place of the god-myth in our lives, that can deal unapologetically with the notion of evil and good, why shouldn't that be something where we proudly say, 'We're artists. We have an intense and wide-ranging vision'?"

The Conjuring Of Lord Of Illusions Part 4 - Postproduction

By Anthony C. Ferrante,

(i) Fangoria, No 141, April 1995

(ii) Fangoria : Masters of the Dark

"I've always been of the opinion that there's a large

market out there for good material and the most you can

ever do is do your best work - write your best novel,

make your best movie - and it's really up to the

marketing people to put it out there and communicate it

to the audience. At a certain point the artist has to

say, "I've done what I can do". I've tried to put

elements in there that will appeal to people and that

they'll find engaging. There's magic, horror, three

really persuasive, heroic performances, a bunch of

wonderful villains and special effects up the kazoo.

So everything I know how to do, I put into the movie to

make the kind of film I would go to."

Producing Horror In Hollywood

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 3, April 1995

"As far as many producers are concerned, fantasy and

horror are just the reliable runts of the litter, not

to be really taken terribly seriously. Probably not to

be valued. Certainly not to be analyzed for their

subtext and what they really mean. A lot of them just

see them as little money making machines, as things

they can make a quick buck on and then run for the hills. That's

not what I'm interested in doing. If they're

interested in doing that, then it becomes a big fight.

I am, perhaps stupidly, increasingly stupidly,

dedicated to trying to hold on to the value of the

mythologies which I initiated. Hellraiser IV has been

more of an effort than I wanted it to be just trying to

make people realize that you can't shortchange an

audience... To be perfectly honest with you, I'm

beginning to run out of temper with it."

Surrealist Artist

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 3, April 1995

"Imagination is a life-line that runs through our culture connecting the dream lives of today with the dream lives of those who went before us. It connects us to a source of knowledge and, potentially, wisdom. And if we sever that line, saying, 'I'm only interested in Freddy movies'... or whatever the current fad is, then we lose access to the great minds that preceded us."

The Thief Of Always

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 3, April 1995

"I would love to some day do an erotic thriller or a big piece of science fiction. I'd also love to do a fantasy, maybe do something autobiographical eventually or even a musical with dancing, where the girl at the end of the chorus line will not lose her head... Why repeat yourself? Life's too short!"

Candyman 2

By Todd Franch, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 3, April 1995

"The whole point of 'Candyman II' is to enrich the mythology of the first film. I think it's going to end up more baroque than the first one, as much a consequence of locations than anything else. I think this movie will answer a lot of questions that were left unanswered at the end of the first 'Candyman' picture."

Lord Of Illusions - Filming The Books Of Blood

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 3, April 1995

"This movie is a little like 'Chinatown' meets the 'Exorcist'. It has a 'Chinatown' feel to it: mystery, beautiful women, terrible secrets. And then it has demonized forces, treated deadly serious, the way the 'Exorcist' did. It's much more like a collision course. I take the scares in this movie extremely seriously. The tongue is nowhere near the cheek. The intention of this movie is to give people a profound sense of dread and send them out of the movie thinking, 'I tasted something, I felt something.'"

Pin Head Speaks !

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 3, April 1995

"I think that [Pinhead's] makeup, without Doug inhabiting it, would have been a very different experience and, I have to say, a lesser experience. It was a marriage of face and mind - mine and his."

Horror Visionary

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 3, April 1995

"I think living is essentially an horrific experience. I think there are many things about being human which strike me essentially as being horrific. Starting with the business of our physical frailty, the capacity for insanity, the capacity for terrible inhumanity, the capacity for carelessness, evil, dishonour and so on."

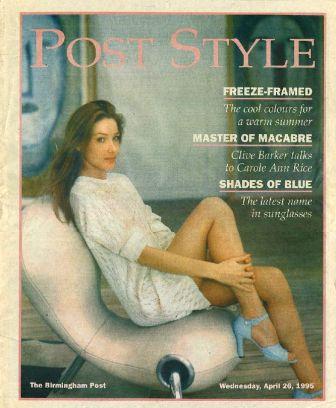

The Birmingham Post, 26 April 1995

Master Of Macabre Is Sweetness And Light

By Carole Ann Rice, The Birmingham Post, Style section, 26 April 1995

"Nothing frightens me. The mechanisms of scaring people have been consistent with storytelling throughout history. I lay money on the first horror story told being about the dead. The unknown is scary. Things that can lead up to death are scary, like violence or breaking the body surface. The audience will feel it if they care about the character you've portrayed."

A Kind Of Magic

By Maitland McDonagh, The Dark Side, No 45, April/May 1995

"I like being scared at movies. I love the delicious

- and it is delicious - tingle of dread that

comes when you're in the hands of a master filmmaker

who wants to make you feel scared, wants to make you

feel the jeopardy of the character, wants to intimidate

you. I don't get it often enough.

"Horror movies are still a place where the cinematic

imagination is unleashed. You can go into a horror

movie and, if it's a good horror movie, you can still be

genuinely surprised. You can still be shown things

that were genuinely not in your imagination until you

sat there in the movie theatre and that's wonderful.

"I'll go a long way to be shown something that I've never

seen before, and I've gone on record saying I don't care

if it's got a zip up its back. The preoccupation with

clinical realism is, for me, far less important than

imagination unleashed. As a viewer, I'm still drawn to

B-movies where the illusion is less than perfect but

the imagination is wild."

Later With Greg Kinnear

Transcript of a TV appearance on Later with Greg Kinnear, 1995

"There's something erotic about monsters. They talk about our forbidden selves... It's the taboo element, it's the things we shouldn't say and the things we shouldn't do - and you know that if someone says you shouldn't do something, that's when you want to do it. Pinhead may not seem like the ideal kind of erotic character but he has some kind of power that galvanises people and, by the way, I didn't plan it that way... I'd be the first to say the audience have told me that. I didn't get up in the morning and say, 'Gee, this is a really hot, sexy character, I can see this, this is a Playgirl centrefold right here.' I just looked at a character who seemed cool looking."

Imagining The Horrific

Talk by Clive Barker / Interview by Kim Newman, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1st May 1995

"I don't feel the ideas I come up with are particularly bizarre. I

think that they're things that have always been with me, and there was

never a moment, there was never a hinge moment. There was never a

moment when I got up... there were moments when I realised other people

were viewing me that way; I remember distinctly sitting around a scout

camp fire and telling stories that at a later point my scout leader

took me aside and said I shouldn't tell the other boys because I was

frightening them. I mean I remember doing that to my contemporaries

and realising that these ideas were inside me to be told by me. But

they were obviously freaking out the other 10 year-olds. So, I suppose

I realised then that I was a little strange."

The Magic Show

By Nick Vince, Clive Barker's Hellbreed, No 1, May 1995

"What fantastic fiction does, in dealing with unreality,

is to reconfigure the possible. What it does is make

us stretch the limits of our imagination and say, "OK,

what if...." In Imajica: what if there was a man who

didn't realise, but was the half brother of Jesus

Christ? In Weaveworld: what if every dream of

perfection, every dream of Eden, every dream of the

perfect world from which we have been exiled - Arcadia,

fairyland, whatever you want to call it - had been

woven into a carpet and hidden away because its enemies

were coming, and supposing one person found that place

and wanted to release it again? What if you had a

puzzle box that could open the doors to hell?"

Shades Of The Illusionist

By Geoff Sweeting, Ex Cathedra, No 4, May 1995

"[Everville] received the best reviews I've had. It's the first time

the New York Times has given a half a page over to a review of a book

of mine, and really taken it very seriously in looking at its

metaphysics and analysing it. It was a great response. And we've

certainly sold more copies of this book than any other I've had out...

"I think that Imajica was the turning point. I think its size and its

great seriousness - going back to the issue of Jesus Christ of course

- was a turning point for critics and readers. It was the point at

which the critics said, 'We have to take this bastard seriously.' "

Hard-Working Fantasy Man

By Katie [ ], The Irish Times, 30 May 1995

"I do subscribe to the Christian elements of love, forgiveness, sacrifice and redemption, but I don't like Christianity's repressiveness, and I don't subscribe to its desire to destroy every god but its own. The Hindus have 33 million gods and that's fine. The patriarchal structure of Christianity is not attractive to me either, nor is the idea that the only people who can save us are men...

"Women in fantasy are either goddesses or whores. Maeve [O'Connell] is both. She is named after a Celtic goddess and she ends up running a brothel. Everville is founded around the best bordello in Oregon. I was researching 19th-Century American history and I discovered that women were most powerful as madams. They couldn't become sheriff, but they could be a madam.

"The fact that Maeve is the founder of Everville is obliterated, because history represses things we don't want to know about. It is the old story: the founding mothers are forgotten while the founding fathers are enshrined."

Confessions

By [Stephen Dressler and Cheryl Bentzen], Lost Souls, Issue 1, [June] 1995 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"I do believe that after death we take journeys, and I do think that

the life that we are living now in the flesh with this particular name

attached is just one part of a much larger experience. So to that

extent I completely believe, in the sense that I've written about life

after death, I certainly believe that that's part of what this being

business is all about and that there are journeys to take, after we've

left the body, which will be startling and extraordinary and

revelatory. I think we have hints of that, I think in our lives before

death we have hints of the great panoramas which await us. I think in

moments of epiphany, we sense our spirits seem to open up. They seem to

unfurl like the sails of some wonderful sailing ship. Suddenly we have

possibilities in our grasp that we didn't have a moment before. All

kinds of things can do that to us, the sight of a certain kind of sky,

a certain kind of smell in the air, the presence of a certain animal,

the presence of a certain person, the wind, gulls; any number of

things can be triggers for this opening of our perception. What we see

when we enter those brief moments of epiphany, what we feel, is

possibility. What we feel is fearlessness. What we feel is that all the

anxieties and apprehensions which cluster around us because we live

in a fearful world are actually things that we will have to work

through but they're finally redundant. There will come a time in our

lives, maybe at the very end of our lives, when those fears will no

longer be important. When they will drop off like the dead skin off a

snake and something new and beautiful and bright will emerge. "

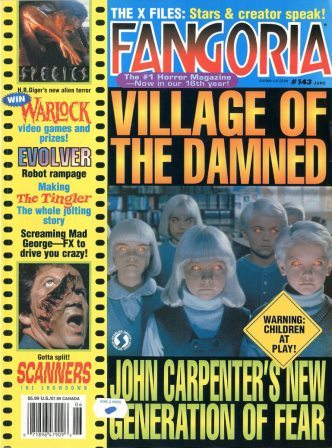

Fangoria, No 143, June 1995

Illusions Update

By Anthony C. Ferrante,

Fangoria, No 143, June 1995

"We've been in long discussions about when the movie should be released. We were going to go out on May 12

but we would have been trampled. The next weekend it's Die Hard: With a Vengeance and the following

weekend it's Crimson Tide. So now it looks like late summer...

"Working on a film is different from a novel. Test screenings are the equivalent of showing someone your

first draft, which you never do. Nobody will see a book until I've done three drafts and a polish. So

after the screening, we went back and had the extra time to work on the picture."

Time Warner, On The Defensive For The Offensive

By Howard Kurtz,

The Washington Post, 2 June 1995

"I'm not going to defend some piece of sleazy, scummy entertainment that's just done to make money. But if an artist wants to deal with violence or sexuality or images of darkness and horror, those are legitimate subjects for artists."

Clive Barker: Crossing The Thresholds

By David Howe, Shivers, No 19, July 1995

"I think that one of the things that Fantasy does best... is that sense of the

dynamic between something transcendent and something infernal and terrible. I

think that good Fantasy isn't all about unicorns and elves, it's not cutesy. Good

Fantasy, whether it be A Midsummer Night's Dream or The Tempest or portions of Chaucer

or CS Lewis or Tolkein or Mervyn Peake... we could go on, makes you very aware of

the dynamics of experience.

or CS Lewis or Tolkein or Mervyn Peake... we could go on, makes you very aware of

the dynamics of experience.

"I'm a forty-two year old man who has watched people die. Not a lot of people,

but more people than I thought at the age of forty-two I would see die and I think that

does change the way that you write because it changes your own experiences. I think

that you just have to accept that as a writer you are to a large extent shaped by

your experience. Since I last saw you I've been with people when they've died and

that changes the way you look at the world. People very dear to me have gone - some

of AIDS but not all by any means - and I don't think I expected that. One of my

very dearest friends in all the world who was the theatre critic of Time magazine died

of a heart attack last year, and he was two years my senior. He was one of the great

good guys of the world. Events like that make you re-evaluate your own life.

You look again at the experiences that you had, at what you're giving and what you're

taking. And I think it's important that, if you're honest, then you're speaking

out of your own experience of the world. Writing Fantasy is not a form of

escapism, it's a form of discovery. I've said that from the very beginning about

writing Fantasy, Science Fiction or Horror: imaginative fiction is not an

escape, it is a form of encoded confrontation. "

The Candyman Cometh (Out)

By Peter Burton, Gay Times, July 1995 (note: large portions of the interview are identical to the February 1995 interview in The Advocate)

"I don't see anything wrong in finding - constructing - ones's own jigsaw of faiths, finding wisdom anywhere. Because we stand outside conventional systems, gay men have a view of faiths and dogmas which is particularly useful. 'What can I use?' we ask. 'How can I grow?' 'How can I be wiser?' 'How can I be healthier?' 'How can I be more loving?' "

Sexy Human-Alien Monster Is Work Of Swiss Painter

By James Ryan,

The Plain Dealer, Cleveland, 2 July 1995

"By and large, Hollywood has seen

[Giger] as a monster maker. As a painter, he's undervalued.

"Though there's Sphinx-like beauty and ambiguity in what's on the canvas, what comes out on the screen is largely monstrous...

Giger seems to be painting aliens, but the closer you look, the more you realize he's painting twisted versions of us. That, to me, is

much more disturbing."

World Weaver

By John M Farrell, Hot Press, Vol 19 No 13, 12 July 1995, (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"I think a book should be like a great conversation, and the great conversations are the mellow ones, the ones where you come away thinking, 'That was amazing, I had a time there'. Very seldom are they like debates, they're not debates, they're feelings out of each others' complexities, yeah? You think stuff through and, instead of coming at him or her like a speeding bullet, you let that particular idea advance in your own head and it's a very complex moment - intellectual, emotional, philosophical, many-levelled, historical. If you're having a conversation with friends, it often refers to earlier conversations, earlier feelings. A Hollywood movie relates to that kind of conversation by employing a slap in the face. That's the Hollywood experience. Pow! Pick yourself up. Go have a pizza."

Two Months Later, No Indication Dole's Slamming Has Curbed Hollywood

By [ ],

The Associated Press Political Service, 30 July 1995

"When I get up in the morning and work on writing a screenplay, the last thing in my head is Bob Dole... I just don't think any storyteller worth his or her salt cares what anybody outside of his or her imagination thinks. You just can't do that,"

Barker's Bite

By Anthony C. Ferrante, huH, Issue No 12, August 1995

"We're not skimping on the viscera - [Lord of Illusions is] a pretty strong movie. It also has a lot of the qualities which will endear it to an audience that wouldn't

be so keen on the viscera flying. I think we're making a class act which has eruptions of weirdness and violence. This environment is sort of like a little corner

of hell. And I like that combination. The picture has a big budget look and feel to it - it's beautifully performed and photographed - but then you've got a lot of this

nastiness which you normally don't get with pictures like this.

"This isn't an homage to 1940's detective movies like 'Angel Heart' was. This is not going to be a movie full of immaculately backlit women with a lot of smoke.

This is not going to be about Venetian blinds and ashtrays with cigarettes left burning with lipstick on 'em. What we have, though, is a hip, interesting, brave

Everyman who is drawn in the Heart of Darkness over and over again because of some karmic thing which he has no power over. I think that will be fun to watch."

Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Clive; A Downright Polite Hellraiser Shows His Artistic Side In Costa Mesa

By Zan Dubin, Los Angeles Times, 12 August 1995

"We never think, do we, that the [actor] who plays Macbeth has to have

committed murder? But you'd be amazed at the number of people who come

into this house for an interview and say 'I didn't think you were going

to be like this.' And I say, 'What do you expect, that I'm going to be

totally corrupt, that some how the imaginative journeys that I've

taken have left some terrible scar on me?'

"Just because you allow in the human body, just because you allow in the

facts of death, just because you allow in the possibility that we all

like to get scared once in a while, does not remove morality. It does

not remove the notion that I know the difference between good and bad."

Lord Of Illusions

By Robert DuPree, (i) Subliminal Tattoos, No 5, Summer 1995 (ii) Rage, No 8, October/November 1995

"We live in a state of repressed fear; there are things we put out of

our consciousness because if they were central to our our consciousness,

we couldn't get on with the business of living.

"Well, look at me: I'm living on the fault line! And it's been said

that if you join up all the hospitals in San Fransisco, say,

they describe the San Andreas fault - whether that's true or

not, the fact is that we live with bodily frailty, we live with the

danger of getting in an automobile crash, we live with the imminence of

death and the loss of our loved ones. But we cannot constantly

think about those things, because if we preoccupy ourselves

overly with them, we'll fall apart at the seams.

"So I think what we do is ritualize those things. We say, 'Alright,

there are times when we will talk about these things. We will

gather together, the the name of things we fear, and we will dissect

these things in a public forum.' Because we're all together, and

jumping and shuddering at the same time, we have the comfort of

knowing that, even though we are confronting these things, they are not

our problem alone; they belong to us collectively, as a species. The

horror movie is the perfect vehicle for that collective act of

expurgation."

Horror Is Creeping Back Into Vogue

By [ ], New York Times, 13 August 1995

"I always identify with the villain. You wouldn't go to see a movie called Van Helsing, but you would go see Dracula."

Clive Barker And His Visions Of Horror Art

By Henry Sheehan, The Orange County Register, 14 August 1995

"The great thing about painting is that it can be about everything, and yet you're

not demanding any specific interpretation from the viewer. The painting is there, it's

what I felt at that given moment, make of it what you will. That's very important to me,

because the movies clearly are populist pieces designed to stir up an audience and give

them some excitement on a Friday night.

not demanding any specific interpretation from the viewer. The painting is there, it's

what I felt at that given moment, make of it what you will. That's very important to me,

because the movies clearly are populist pieces designed to stir up an audience and give

them some excitement on a Friday night.

"I hope they last until Saturday morning, but the truth of the matter is that they

essentially have to work for an hour and a half on a Friday night. The books are large,

dense journeys, very layered and they're the result of 18 months of me just working to

make things as rich as possible. But they nevertheless are going to take the audience on

a very specific journey.

"The paintings are for me as an artist, and I hope for the spectator, like stepping out

of a labyrinth into open air. It's not a test, it's not a quiz. It may be a puzzlement,

but I don't have an answer to it, or if I have an answer, my answer is no more relevant

than your answer."

Late Show

Transcript of a TV appearance on the Late Show with David Letterman, 18 August 1995 (Clive didn't get to say anything...)

San Francisco Examiner, 21 August 1995

Mining The Dark Side

By Jane Ganahl, San Francisco Examiner, 21 August 1995

"Maybe I'm being too New Age about this, but I feel like there's nothing wrong with taking the journey into darkness as long as you deliver the audience to the other side."

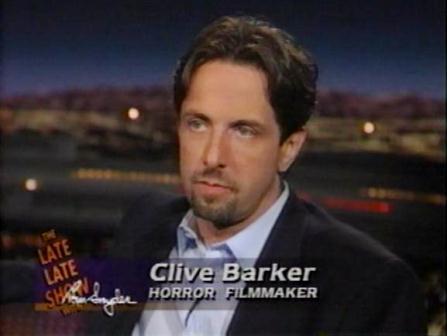

The Late Late Show

Transcript of a TV appearance on The Late Late Show with Tom Snyder, 22 August 1995

"Film Noir is one of my passions and detective movies are one of my

passions. So I've been writing for ten years now about a detective, a

The Late Late Show with Tom Snyder, 22 August 1995

New York P.I., called Harry D'Amour and Harry comes out of the Hammett

/ Chandler tradition, he's a Sam Spade / Philip Marlowe-esque kind of

guy. He loves his life, his divorce cases, his insurance fraud cases.

Unfortunately he is beset by magical interventions of various kinds,

supernatural interventions of various kinds - he cannot get through a

case without something supernatural happening. Lord of Illusions takes

him through from the world of illusion - of David Copperfield, if you

will - through to something much darker. Bakula plays D'Amour, Bakula

embodies D'Amour for me because he's an accessible, regular guy in

deeply extraordinary circumstances. Terrifying circumstances...

"The detective character is such a staple of American cinema and it

seemed to me, what a great combination it was to take the detective

character and to put him in a horror movie and watch him follow the

clues through to uncovering secret after secret. And, of course,

following the most beautiful woman in the world to do so."

AOL Appearance - Opening Night Of Lord Of Illusions

Transcript of on-line appearance, 23 August 1995

"I don't think I write horror fiction as such. Imajica and Everville, for instance, seem to me better described as fantasy. But however we choose to describe them, the fact is our minds are one glorious imaginative country. Just because I discovered Edgar Allen Poe doesn't mean I ever forgot the way to Never Never Land."

Interview

By [ ], Drama-Logue, 24-30 August 1995

"[Harry was] inspired from three sources - Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe and 'Kolchak: The Night Stalker'. But I don't think of him as being that different from any of us. I think the dark side has a hold on all our hearts."

Cathy's Tale Of Two Leapers

e-mail diary note of meeting Barker in New York, August 1995 By Cathy (note : full text used to be online at the Red Zone)

"[Lord of Illusions] is not that gross, really. It's more that it will really scare people... It's OK because, right there in the middle of it is Scott. And he'll lead you right through it."

Click here for Interviews 1995 (Part Three)...