Interviews 1995 (Part Three)

Lord Of Illusions

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 5, August 1995 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"My enthusiasm never ran out, but God, my energy took a dive. But, I

don't know anybody who directs movies, who wouldn't say that about the

filmmaking process. It's almost a universal truth. Particularly if

you've written the thing and you're also producing or co-producing, as

I was in this case. A lot of responsibility lies on your shoulders and

we were really trying to push the envelope on the genre. I mean, we

weren't taking about a guy with an axe in a dark house. We were putting

things on the screen things that hadn't been seen before and nuances

that hadn't been felt before and that means you've got to be watching

really, really closely and working really, really hard to pull off

something fresh, without all the money in the world.

"I drink indecently large amounts of caffeinated tea. I think that's

the Brit in me. But, I'm always looking for anything that can give me

a kick in the pants. On the sets I could be seen chewing ginseng at

various times. I picked up this thing about snoozing from [David]

Cronenberg, who actually has built into his shooting schedule a nap

time for himself and I guess any of the other crew who want to avail

themselves of it. For me that's really important. I always have a

siesta during the days I'm writing. I think current medical opinion is

that it's actually supposed to be better for us than we ever thought.

Siestas are actually very healthy. You know, 10 or 15 minutes is all I

need. I catnap; I close my eyes and 15 minutes later I'm definitely

more awake and more focused than I was before the nap. I also exercise.

I work out at the gym four times a week when we're shooting. I think

that's useful."

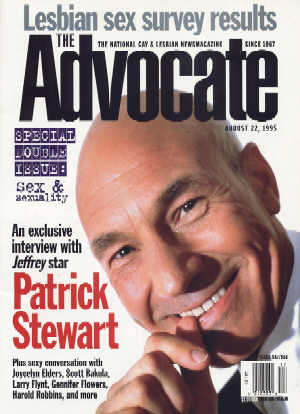

Great Scott

By Tom Provenzano, The Advocate, Issue 687/688, 22 August 1995

"Scott [Bakula] brought his kid onto the set on a day when we were working on some very dark stuff.

I could not imagine a more wonderful contrast. 'Welcome to Clive Barker's world,' said Scott to his kid. This hellhole!

"It was a big scary set. The kid was looking at these horrible demoniacal forms on the wall.

Scott was saying, 'It's just a dragon,' going around and interpreting each of the things on the wall

in the most benign ways. For me, that was the touchstone. Here was this regular guy with this

lovely child, just saying, 'That's not scary, it's just a dragon.' If it was me, it would have been the

reverse, interpreting everything as fucking terrible, terrifying things that will eat your head off."

Barker's Carnival

By Mal Vincent, The Virginian Pilot and The Ledger-Star, Norfolk, 24 August 1995

"I was irritated that on the night The Silence of the Lambs won the Oscar, no one seemed to admit that the intention of the movie

was to horrify people. They didn't want to admit that a horror movie, finally, had won the Oscar.

"We are all drawn to the dark side - to things that simmer just below the surface. When we see a wreck on the highway, everyone slows down - not

because they want to see the cops in action but because they want to see if there are any bodies. It's nothing to be ashamed of.

What is problematic is that it is thought to be weird. But we are told not to like the monsters. We are told to think that they are evil.

It is a lie. It is a damnable lie.

"We are taught that some things are distressing. When you think about it, why are the flying monkeys in The Wizard of Oz images

of terror? Actually, they're kinda neat. The drama teaches us that they are terrible."

Threshold Of Pain

By Phantom Of The Movies, New York Daily News, 24 August 1995

"The Omen was a particular model for us because it's a very classy movie with some very visceral things in it. I wanted to make a picture that aspired to that kind of level - good storytelling, solid performances and, well, David Warner's head bouncing on a piece of glass. I would like people to come to Lord of Illusions and feel like, whether they like the movie or not, there was a serious attempt to make a thinking man's horror movie...

"What I try to do in this picture is give the audience a good menu of potential images of fear and distress: psychologically, we play with people's heads, we have hallucinatory stuff; we play with people's bodies, with piercings and impalings; we also play with the stuff where the audience is just discomforted because they're in the company of characters whose world-view is totally different from their own."

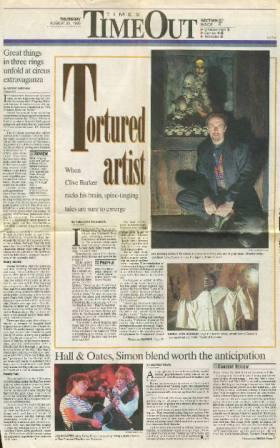

Contra Costa Times, Time Out section, 24 August 1995

Tortured Artist

By Reed Kirk Rahlman, Contra Costa Times, Time Out section, 24 August 1995

"A horror book's primary intention is to horrify. My books have horrific passages, but then so does the Bible - and Lord of the Rings. My books are about journeys toward revelations, where information and secrets can be found. Horror stories are journeys to death.

"There are things you can do in books that you can never do in movies. Complex psychological things. About ambiguity, about paradox. It's not something that can be delivered in a movie that is going to open on 1,500 screens. I push it, but the audience wants something fairly direct in their 100 minutes of entertainment.

"[My movies] are unapologetically seated in horror. I want the audience to jump and squirm. Yes, I want to tell a story that's compelling. Yes, I want everything to look great. But it's all in service to the clammy palm. That's a long and honourable tradition.

"I go for the jugular. I try to blindside with images, the best of which tend to be irrational... I don't know why the demon Pazuzu makes Linda Blair's head turn around. It doesn't make a whole heap of sense. On some level, horror movies are about images that erupt irrationally. This may be why critics have difficulty with the genre. On some level they defy analysis. A horror movie should drive you beyond thinking about them by their primal force."

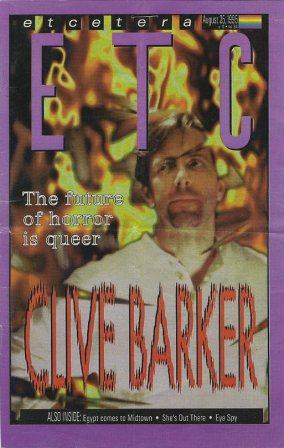

The Future Of Horror Is Queer

By Brandon Judell, (i) ETC, Vol 11 No 34, 25 August 1995 (ii) Outlines, September 1995

"I want as many people as possible to know that these imaginings come from a gay man who's happy to be gay. One who's making work which will be read by straight readers and enjoyed by straight readers. I add nothing special for gays in my fiction, but they are part of the world I create and constructively so."

Imp Of The Perverse

By Sean K. Smith, LA Village View, 25-31 August 1995

"As human beings, if we're confident, we want to do many things. We want to say, 'Give me a chance, let me have a go at it. I may fall flat on my face, but let me have a go at it...'

"I feel as though I am more confident about being personal in my statements as time goes

on. Indeed, my work is less generalised than it was, more rooted in who I am. I almost want to say confessional. And I suppose that's because I feel as though I have my readers, my viewers, who are interested in that. And so maybe I'm more likely to take something autobiographical and put it in without discomfort than I used to be. Certainly in the new book I'm writing, there's a lot of biographical detail.

"Someone's doing a biography of me now, and I've said on a number of occasions that it's an interesting thing, doing a biography about somebody who really pours their subconscious into their work, because you wonder what there is to discover. It's sort of there on the page. It's just encoded. I've just changed the names to protect the guilty."

Scott Bakula's Bum Deal: Star Nixes Nude Shot

By Bruce Kirkland, Toronto Sun, 26 August 1995

"I would not have allowed myself to make a movie that had its roots in noir in which a woman as beautiful as Famke Janssen was encountered by a man as handsome as Scott Bakula and they had not, at one point, locked lips. I mean, it's my duty, right?"

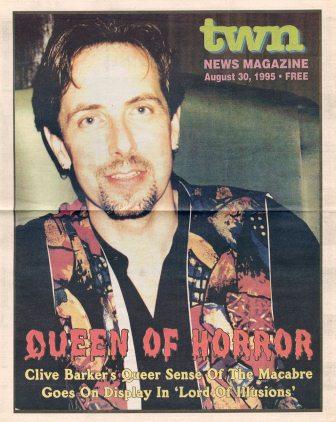

TWN, 30 August 1995

Clive Barker, Happy Homo Horror Hero

By Steve Warren, (i) San Francisco Sentinel, 23 August 1995 (ii) Au Courant, 29 August - 4 September 1995 (as 'Horror's Homo Hero') (iii) TWN, 30 August 1995

"In the broader sense of things, death is an inconsequential business;

but in our

day-to-day lives of visiting hospitals and attending memorial services,

it's damned near

impossible to put it into perspective...

"As a gay man, I've seen a lot of my friends die, far more than I

expected to or am

supposed to. And while I mourn them, I don't think for a minute that

I'll never see

them all again. My faith hasn't been diminished at all."

Confessions

By [Stephen Dressler and Cheryl Bentzen], Lost Souls, Issue 2, [September] 1995 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"There's always elements of who I am in things. There is no single

character that I could point to and say, well that absolutely,

unequivocally is me. But, there is a lot of the young Clive Barker in

little Harvey. There is a lot of the early twenties Clive Barker in

Cal Mooney. There's a lot of the older Clive Barker in Gentle. Some

of that is about, simply a reflection of geography. I'm a Liverpool

boy, and Cal is a Liverpool boy. The houses that are described are the

houses that I've been in, and the locations are locations that I know

very well. I use a lot of details of my life in Liverpool to contact

Cal. But there is a whole bunch of other stuff that is necessary for

the narrative, I mean I've never worked in an insurance firm. I don't

think I would be so prone to forgetting wonderland as Cal is. I think

I'm less brave than Cal is, so there's a whole bunch of differences

there. Little Harvey is the kid who's bored with the world, and

irritated with things and how things move along. Why does there have to

be really boring days, and why can't there just be good bits in

life? That's a mingling of something I felt when I was a kid, and

something I'm very aware of myself still doing. The Thief of Always is

me telling myself off to some extent and reminding myself that what

we have, right now, is very important to us and the people who we have

around us right now will not be with us forever. We have to remember

to take each moment and find the best of it. That's very much a part

of the young Clive Barker, and at the same time even the man I am now.

Gentle, who is an incredibly contradictory and complex character, with

huge ambition always gets waylayed in some way or another. He keeps

going after possibilities and stumbling upon things and then losing

his way again, all of that feels very much like me. I don't think that

it's a particulary pretty portrait, but there you go. Certainly the

Gentle in the third part of the book is drawn upon things that I felt

and feel. I would not go as far as saying that it was a portrait, I

wouldn't say that of any of these characters, but the old reference of

things that I thought of and places I've been are there. "

Clive Barker Talks About Lord Of Illusions

By Stephen Dressler and Cheryl Bentzen, (i) Lost Souls, Issue 2, [September] 1995 (ii) Combined with 'Hell's Events' (see below) in Trauma, No 5, October 1996. (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"If I were to take any story out of Everville and Great and Secret Show and follow it through in movie form, I would say that it would be Tesla's story. The fact is that you can't tell that breadth of a story in a movie. You might want to take one strand of it, and if you had any strand of it I think it would be Tesla's story. I think Tesla is a very interesting character. Having said that, my immediate follow up is that I still think that it is pretty unlikely just because it is very, very difficult to turn a book of that scale, books of that scale, and remember we haven't finished telling that story yet, into the space of a regular movie. You certainly don't want to do a tv series because what we are seeing is the mini-series problem, and Weaveworld is slightly easier because it's a single book, but you couldn't turn three books the length of Great and Secret Show into a mini-series."

Hell's Events

By Stephen Dressler and Cheryl Bentzen, (i) Lost Souls, Issue 2, [September] 1995 (ii) Combined with 'Clive Barker Talks About Lord Of Illusions' (see above) in Trauma, No 5, October 1996. (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"These [The Forbidden and Salome] are home movies, they are movies that were made in people's cellars and people's front rooms, with a lot of passion and no money. I think they are interesting little films, almost a thing prophetic about them in a sense, particularly in 'The Forbidden', the atmosphere of dread and anxiety that hangs over the movie and obviously the erotic elements and the nails in the nail board. These definitely prefigure what we see later in the Hellraiser movies. I think they are an interesting artifact, and I am glad they have found their way to video. Just for the average filmgoer, they wouldn't mean a whole heap. For people who are really familiar with my whole mythology and my approach to things I think they are an interesting piece of insight into how these images and ideas developed over the years."

Bakula's 'Leap' To 'Lord Of Illusions' No Easy Trick

By Luaine Lee, Los Angeles Daily News, 1 September 1995

"People are fascinated by secrets; the things you're not supposed to know, not supposed to look at are, more often than not, the

thing people do want to look at, do want to know. It's that thing about forbidden fruit, withholding information from people. We all

know this: 'Don't go into the locked room.' 'Don't look under the bed.' Instantly you can't help yourself.

"It may not be about power as we conventionally know it. But the occult has to do with gaining power in strange ways - magical

power. I know as a kid, for instance, the notion of having magical powers was deeply attractive and it was about being able to frankly

dominate other kids. I was this kind of nerdy kid. I thought, 'Gee, it would be nice to fly rings around people, be able to give them

the evil eye and watch them keel over. That would be kind of cool.' "

Barker Returns To The Horror He Knows So Well

By Russell Lissau , The Baltimore Sun, 1 September 1995

"Scott Bakula is a very fine actor who's an everyman. Playing Sam Beckett, he was an ordinary man in extraordinary circumstances. He was always a regular guy, a very nice guy. To then put that personality into a Clive Barker movie, an interesting dynamic appears, one which would not have appeared if people did not know who Scott was. What's doubly interesting is that there is a dark side to Scott; it was not at all difficult for him to enter this world, to immerse himself in this world."

AOL Appearance

Transcript of on-line appearance, 1 September 1995 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"I don't have evidence of influences by other beings through dreams, but I certainly don't discount the possibility. If they exist it seems likely to me they will be both good and bad, as that certainly seems to be true of our species."

The Conjuring Of Lord Of Illusions Part 5 - The Last Interview

By Anthony C. Ferrante, Fangoria, No 146, September 1995 (Note: interview took place in 'early Spring 1995')

[on the first test screening] "By and large, they didn't

like the explicitness of the sex. It surprised the hell

out me. I don't know why. From the bottom of my heart,

I don't know. I think horror fans are used to sex scenes

being a prelude to death. They're used to sex scenes

being about murder and this one wasn't. If one of the

characters got out of bed and got a spear through the

chest, they might have been perfectly content. They

felt people talked too much. I think audiences are used

to horror movies being 90 minutes and then get the hell

out of there and our theatrical version is 104 minutes,

so it's still 14 minutes longer than a Nightmare On Elm

Street picture. I happen to like movies that spend some

time on character.... One of the things that happens is

that, if you take a few dialogue scenes out and pare

them down, the acts of violence get closer together and

the feel of the movie is more intense. Now suddenly you

have this picture that is really going for the jugular

and doesn't give you a moment to breathe since, of course,

I took out what few moments there were where the

audience was allowed to breathe.... At the second

screening the numbers doubled. They said it was the

scariest movie they'd ever seen. The sex was pulled

back, the violence was not."

The Gay '90s - Entertainment Comes Out Of The Closet

By [ ], Entertainment Weekly, No 291, 8 September 1995

"It just seems like a good time to stand up and be counted. It's important that as many well-known gay men [as possible] say, 'Yes, I'm gay.' It doesn't turn me into someone who's going to molest your children, folks. It's just an expression of my nature, and you should stop making a big drama of it."

Gay Heroism, Tales Of Transcendance

By Orland Outland, Frontiers, 8 September 1995

"The real world as we know it is a moveable feast. I think people know that we make reality. We spend a third of the day asleep, wandering in other realities. We sit on the bus, or at our desk, and our minds float off to other places. Of course, white rabbits aren't going to run past us looking at their watches, but in both our heads the white rabbit is a powerful figure. He's been wandering around my head since I was four; I can see the Tenniel drawing of him very clearly in my mind. The thing about the fantastique is that it moulds itself to the changing self you are. What Alice meant to you at four is, I'm sure, different that what it meant when you were 14, and 24. If you're reading something very much about a particular place and time, the chances are it's going to mould less well with your changing self.

"Shakespeare is the grand example: the great Shakespeare plays are all things to all men, and there's an element of the fantastic in practically everything he wrote; the history plays have ghosts, visionary dreams and prophecies, wild and extraordinary events, and this was all taken for granted as normal. And with the rise of the naturalistic novel, naturalism or realism, whatever that means, has come to seem like the norm, and the fantastic has become the oddity.

"But a lot of people have an appetite for this. Stephen King is the most popular author in the world, Anne Rice sells a lot of books, I sell a lot of books. Some people will see any movie with a supernatural angle. But in Hollywood, the problem is that the large studio fantastic movie becomes an excuse to sell Happy Meals, rather than coming out of a genuine desire to expand the imagination. In contrast, look at 2001, a movie designed to blow your mind - Stanley Kubrick couldn't give a shit about Happy Meals! Nobody said then, 'Stanley, when the starchild appears, could he be carrying a Big Mac?' I try to make movies that don't cost much, because then there's not that pressure to recoup costs through marketing deals."

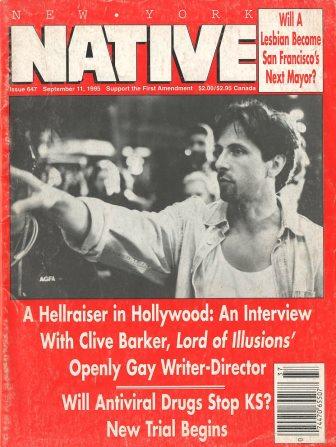

New York Native, No, 647, 11 September 1995

Outré And Proud

By Bob Satuloff, New York Native, No, 647, 11 September 1995

"It takes me 18 months to write a novel. In that time, you go through lots of phases. It takes a year to make a movie. Again, you go through phases. Some of them are emotional and about gut response, others intellectual, when you ask yourself what it is you're saying. I try never to let my intellect censor my emotions. I trust my gut more than I do my brain...

"What starts the process going is an image or an idea, something that sticks in your mind and needs to be spoken. Then, for me, it's the piece of sand around which the oyster will eventually make a pearl just because it's so fucking irritating. It's in there, in the flesh, and you have to somehow deal with it. I deal with images that obsess me, concern me, haunt me, by wrapping stories around them, threads of ideas. When a draft of a novel or a screenplay is finished, I'll step back from it, and that's when the intellectual process begins to kick in. I hand write everything and I never look back over what I've done until the draft is finished."

Candyman 2

By [ ], Candyman 2 US Press Kit, 1995

"With children, their beliefs are stronger than adults and they exist in that magical state where anything is possible. Children disseminate urban legends because they're at that age where it's difficult for them to tell the difference between reality and fiction. The story about the little boy who had his genitals cut off by the hook-handed man was told to me by my grandmother when I was six years old. She was trying to tell me to be careful of strangers, but I remember being terrified for weeks. Of course, that didn't stop me telling that story to all my friends at the playgound and I used that story in the first Candyman."

Clive Barker

By John Frame, transcript of an interview on Queer Radio, Brisbane, Australia, 18 October 1995 (note: full text online at www.queerradio.org)

"One of the things that makes horror movies interesting is there's a

sort of 'rite of passage' element to horror movies. There's a kind of

initiation quality to horror movies. I think one of the reasons why

they're so popular with young people is that you almost dare a horror

movie to do it to you. You go into a horror movie and if it's half

worth anything there's a little tussle going on constantly with the

movie in which the movie is trying to outwit you, the movie is trying

to blindside you. And my job as a director is to put these images and

these ideas and this dialogue and this music together in a way that

constantly keeps the audience on their toes.

"The first ten minutes of Lord Of Illusions are very intense. The stuff

before we even get to Harry (the Scott Bakula character) is deliberately

constructed to be a very intense sequence of images and ideas, so that

the audience is, I hope, intimidated. So that by the time you get to

the eleventh minute and Bakula appears, you say. 'Wow, thank God -

somebody I can hold onto in this storm of distressing images.' "

Lord Of Illusions

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 6 / Vol 27 No 1, October 1995

"I wanted a more spectacular ending for [Nix] but we didn't have any money for something really spectacular in the way

of a demise. And then [United Artists] came across and said, 'You know if you want to blow him to pieces as an

articulated animatronic puppet, here's the money!' So we did just that!

"I think it's really helped give it a sense of completion. One of the interesting things is that because this movie is not

about the monster, it's about the hero, we're never going to bring Nix back. It's over! If there's a sequel to this picture

there'll be a new villain. So it's not as if we have to preserve the guy. He can just go to hell in a handbasket and that's

just fine. It's very satisfying now because we really do demolish him in no uncertain terms, with pieces of his burning

flesh flying towards us! There's no doubt now that this man ain't coming back!"

Dream Demon

By Paul Burston, Attitude, No 19, November 1995

"I think part of our fascination with monsters and demons is the sexual

energy they embody. As civilised human beings, we draw a shade over

things. We don't want to see the world as a kind of sexual chaos,

which is how I see it. Yet we are drawn by primal needs - the need

to sleep, the need to eat, the need to fuck. These are the appetites

which drive us, and over which we plaster these complex rituals,

philosophies, interactions and dialogues. The demon strips all that

away. He isn't civilised. He doesn't have a great vocabulary. He

certainly doesn't have a philosophy. He's just this great ball of

energy. The confrontation with that energy is either going to destroy

you, or it's going to transform you."

Hellraiser IV - Bloodline

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 27 No 2, November 1995

"Given the number of variables there are, the number of things that can

go wrong, it's a wonder that any good movies are made at all. If you

go on movie sets constantly, you see the tension, you see the dramas,

you see the financial stuff, the inter-personal stuff, the bad

politics or whatever else there is. So it's not surprising, nor should

we be surprised, that so many very conventional, very predictable, very

repetitive things get to the screen because many people say, producers

say, 'I don't want to take a risk with this. If I'm going to invest

my money I would prefer to risk it on something that has been done

before, which audiences have responded to 20 times before and that way

I don't have to worry.'

"When the reviews come out nobody ever criticizes the producer. If a

movie looks shit or has been hurried down the line or there have been

compromises made in the shooting or the casting or the effects, nobody

ever turns around and says, 'Well you know this movie was produced by

X.' So it's always the director or the writer, or both who gets it in

the neck. Often the writer and the director are cogs in a much larger

and sometimes very cruel machine."

Lord Of The Lurid

By Emma Tom,

Sydney Morning Herald, 10 November 1995

"Horror movies play to a very particular audience, almost a cult audience. You can't spend too much money on them because you can't expect too much of a return on them. Clearly a picture like Lord of Illusions is not a movie I'd take my grandmother to. It is a movie designed to offer a very particular audience a very particular experience."

Pinhead Progenitor's New Tack

By Jim Schembri,

The Age, 17 November 1995

"I haven't actually written a horror book for a long time. Everville, Imajica, Weaveworld and The Great and

Secret Show are fantasy books, not horror books. The movies remain unapologetically horror movies,

but as far as books are concerned I've left the hardcore horror days long behind and moved into another

area.

"A natural outgrowth of writing adult fantasy was turning my attention to the kind of fiction I loved

when I was a kid: Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz. The Thief of Always is a pretty gentle

book, really, which carries a straightforward and simple message about not wishing your life away."

IRC Online

Transcript of on-line appearance 26 November 1995 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"I have had, since my earliest memories, the suspicion that our senses do not entirely grasp all that haunts and informs and enlightens our world. In short, I think I've always believed we live - figuratively speaking - on the edge of a vast and unfathomable sea of which we see only the first few yards of surf."

Clive Barker Shatters 'Illusions' About Movie Monsters

By [ ], Marquee, December 1995

"This film goes against the grain of what is going on with horror films. Pinhead and Candyman are, in their way, strangely beloved.

I wanted to make sure no one came out of this wanting to grow up like Nix. I came in for some flack because Nix wasn't all-powerful,

wasn't the Devil in disguise. That was, in a sense, my point. We shouldn't be demonising this character. We should be bringing him

down to our scale. Pinhead is a glamorous figure. [Nix and his followers] are unpleasant, unappealing people.

"We are living in a time when cults are a big deal. We're in a milleniumist phase. People have all kinds of anxieties and address

them in all kinds of ways. There is a proliferation of sub-religious people responding to something that's in the air. The

important thing about this movie is that people don't come out of it thinking it's a good idea to join a cult. The movie would have

been indefensible. I thought that was very important, in the end, for Nix to be a fanatical and pathetic man alone in the dark."

Writer-Director Clive Barker On Launching Harry D'Amour As A Horror Hero Franchise

By Denise Dumars, Cinefantastique, Vol 27 No 3, December 1995

"If there is a series, Harry will go on to the next narrative, and there will be no more Nix,

no more Swann, none of that stuff. We'll be off into different territory. It will be a horror series

driven by the hero. That is a fresh tone, because the last 20 years we've had the horror series driven

by the villains...

"Harry is one of those characters who I've gone back to several times... He's been a great way for me

to get under the skin of some narratives. I've enjoyed that, massively. I like his presence, I like writing

about him. Something about how sanguine he is in the face of these terrible things."

Clive Barker's Lord Of Illusions One Of Best Horror Tales Ever

By John Maglinger, WaxWorks, [December] 1995

"In the director's cut I added twelve minutes to the theatrical version. That's very important

because the additional time really enriches a lot of Scott's scenes. Twelve minutes makes a lot

of difference. Scott's presence is strong in both versions - there's just a little more space

in the full version to get to know him... to familiarise yourself with D'Amour's little quirks...

"I have no dexterity in my fingers whatsoever - I couldn't do a card trick if my life depended on it.

But I love watching it. One of the things I tried to do in Lord of Illusions was play lots of

close-up stuff and, also, some big stuff like Siegfried and Roy or David Copperfield do...

"It is possible that what draws us to this kind of spectacle is the suspicion that, one day, it

is not going to work. The guy's going to saw the girl in half and then not be able to put her

back together again. We don't want to admit to that morbid fascination, perhaps, because it is

slightly shameful."